"I don't remember you," she said, "you were not here when we came before."

"No, my lady," he said.

"There was an old man-I forget his name-but he had rheumatism in all his joints, and could scarcely walk, where is he now?"

"In his grave, my lady."

"I see." She bit her lip, and turned again to the window. was the fellow laughing at her or not?

"And you replaced him then?" she said, over her shoulder, looking out towards the trees. "Yes, my lady."

"And your name?"

"William, my lady."

She had forgotten the Cornish people spoke in so strange a way, foreign almost, a curious accent, at least she supposed it was Cornish, and when she turned to look at him again he wore that same slow smile she had noticed in the reflected window.

"I fear we must have caused a good deal of trouble," she said, "our sudden arrival, the opening up of the house. The place has been closed far too long, of course. There is dust everywhere, I wonder you have not noticed it,"

"I had noticed it, my lady," he said, "but as your ladyship never came to Navron it scarcely seemed worth my while to see that the rooms were cleaned. It is difficult to take pride in work that is neither seen nor appreciated."

"In fact," said Dona, stung to amusement, "the idle mistress makes the idle servant?"

"Naturally, my lady," he said gravely. Dona paced up and down the long room, fingering the stuff of the chairs, which was dull and faded. She touched the carving on the mantle, and looked up at the portraits on the wall-Harry's father, painted by Vandyke, what a tedious face he had-and surely this was Harry himself, this miniature in a case, taken the year they were married. She remembered it now; how youthful he looked and how pompous. She laid it aside, aware of the manservant's eyes upon her-what an odd creature he was-and then she pulled herself together; no servant had ever got the better of her before.

"Will you please see that every room in the house is swept and dusted?" she said, "that all the silver is cleaned, that flowers are placed in the rooms, that everything takes place, in short, as though the mistress of the house had not been idle, but had been in residence here for many years?"

"It will be my personal pleasure, my lady," he said, and then he bowed, and left the room, and Dona, vexed, realised that he had laughed at her once again, not openly, not with familiarity, but as it were secretly, behind his eyes.

She stepped out of the window and on to the grass lawns in front of the house. The gardeners had done their work at least, the grass was fresh trimmed, and the formal hedges clipped, perhaps all in a rush yesterday, or the day before, when the word had come that their mistress was returning; poor devils, she understood their slackness, what a pest she must seem to them, upsetting the quiet tenor of their lives, breaking into their idle routine, intruding upon this queer fellow William-was it really Cornish, that accent of his? — and upsetting the slack disorder he had made for himself.

Somewhere, from an open window in another part of the house, she could hear Prue's scolding voice, demanding hot water for the children, and a lusty roar from James-poor sweet, why must he be washed, and bathed, and undressed, why not tossed, just as he was, into a blanket in any dark corner and left to sleep-and then she walked across to the gap in the trees that she remembered from the last time, and yes-she had been right, it was the river down there, shining and still and soundless. The sun was still upon it, dappled green and gold, and a little breeze ruffled the surface, there should be a boat somewhere-she must remember to ask William if there was a boat-and she would embark in it, let it carry her to the sea. How absurd, what an adventure. James must come too, they would both dip their hands and faces in the water and become soaked with the spray, and fishes would jump out of the water and the sea-birds would scream at them. Oh, heaven, to have got away at last, to have escaped, to have broken free, it could not be possible, to know that she was at least three hundred miles away from St. James's Street, and dressing for dinner, and the Swan, and the smells in the Haymarket, and Rockingham's odious meaning smile, and Harry's yawn, and his blue reproachful eyes. Hundreds of miles too from the Dona she despised, the Dona who from devilry or from boredom or from a spice of both, had played that idiotic prank on the Countess at Hampton Court, had dressed up in Rockingham's breeches and cloaked and masked herself, and ridden with him and the others, leaving Harry at the Swan (too fuddled with drink to know what was happening), and had played at foot-pads, surrounding the Countess's carriage and forcing her to step down into the highroad.

"Who are you, what do you want?" the poor little old woman had cried, trembling with fear, while Rockingham had been obliged to bury his face in his horse's neck, choking with silent laughter, and she, Dona, had played the leader, calling out in a clear cold voice: "A hundred guineas or your honour."

And the Countess, poor wretch, sixty if she were a day, with her husband some twenty years in his grave, fumbled and felt in her purse for sovereigns, terrified that this young rip from the town should throw her down in the ditch-and when she handed over the money and looked up into Dona's masked face, there was a pitiful tremor at the corner of her mouth, and she said: "For God's sake spare me, I am very old, and very tired."

So that Dona, swept in an instant by a wave of shame and degradation, had handed back the purse, and turned her horse's head, and ridden back to town, hot with self-loathing, blinded by tears of abasement, while Rockingham pursued her with shouts and cries of "What the devil now, and what has happened?" and Harry, who had been told the adventure would be nothing but a ride to Hampton Court by moonlight, walked home to bed, not too certain of his direction, to be confronted by his wife on the doorstep dressed up in his best friend's breeches.

"I had forgotten-was there a masquerade-was the King present?" he said, staring at her stupidly, rubbing his eyes, and "No, damn you," said Dona, "what masquerade there was is over and done with, finished now for ever more. I'm going away."

And so upstairs, and that interminable argument in the bedroom, followed by a sleepless night, and more arguments in the morning, then Rockingham calling and Dona refusing him admittance, then someone riding to Navron to give warning, the preparations for the journey, the journey itself, and so here at last to silence, and solitude, and still unbelievable freedom.

Now the sun was setting behind the trees, leaving a dull red glow upon the river below, the rooks rose in the air, and clustered above their nests, the smoke from the chimneys curled upwards in thin blue lines, and William was lighting the candles in the hall. She supped late, making her own time-early dinner, thank heaven, was now a thing of the past-and she ate with a new and guilty enjoyment, sitting all alone at the head of the long table, while William stood behind her chair and waited silently.

They made a strange contrast, he in his sober dark clothes, his small inscrutable face, his little eyes, his button mouth, and she in her white gown, the ruby pendant round her throat, her hair caught back behind her ears in the fashionable ringlets.

Tall candles stood on the table, and a draught from the open window caused a tremor in their flame, and the flame played a shadow on her features. Yes, thought the manservant, my mistress is beautiful, but petulant too, and a little sad. There is something of discontent about the mouth, and a faint trace of a line between the eyebrows. He filled her glass once more, comparing the reality before him to the likeness that hung on the wall in the bedroom upstairs. was it only last week that he had stood there, with someone beside him, and the someone had said jokingly, glancing up at her likeness: "Shall we ever see her, William, or will she remain forever a symbol of the unknown?" and looking closer, smiling a little, he had added: "The eyes are large and very lovely, William, but they hold shadows too. There are smudges beneath the lids as though someone had touched them with a dirty finger."

"Are there grapes?" said his mistress suddenly, breaking in upon the silence. "I have a fancy for grapes, black and succulent, with the bloom on them, all dusty."

"Yes, my lady," said the servant, dragged back into the present, and he fetched her grapes, cutting a bunch with the silver scissors and putting them on her plate, his button mouth twisted as he thought of the news he would have to carry to-morrow, or the next day, when the spring tides were due again and the ship returned.

"William," she said.

"My lady?"

"My nurse tells me that the servant girls upstairs are new to the house, that you sent for them when you heard I was arriving? She says one comes from Constantine, another from Gweek, even the cook himself is new, a fellow from Penzance."

"That is perfectly true, my lady."

"What was the reason, William? I understood always, and I think Sir Harry thought the same, that Navron was fully staffed?"

"It seemed to me, my lady, possibly wrongly, that is for you to say, that one idle servant was sufficient about the house. For the last year I have lived here entirely alone."

She glanced at him over her shoulder, biting her bunch of grapes.

"I could dismiss you for that, William."

"Yes, my lady."

"I shall probably do so in the morning."

"Yes, my lady."

She went on eating her grapes, considering him as she did so, irritated and a little intrigued that a servant could be so baffling a person. Yet she knew she was not going to send him away.

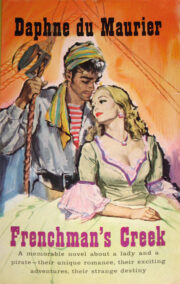

"Frenchman’s Creek" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Frenchman’s Creek". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Frenchman’s Creek" друзьям в соцсетях.