Somewhere there was a house which she had never seen, but he would take her to it, and she would feel the grey walls with her hands. She wanted to sleep now, and dream of these things, and remember no more the guttering candles in the dining-hall below, with the smashed glass and the broken chairs, and Rockingham's face when the knife touched his flesh. She wanted to sleep, and it seemed to her suddenly that she stood no longer, that she was falling too, as Rockingham had done, and the blackness came about her and covered her, and there was a rushing of wind in her ears…

Surely it was long afterwards that people came and bent over her, and hands lifted her and carried her. And someone bathed her face, and her throat, and laid pillows under her head. There were many voices in the distance, men's voices, and the coming and going of heavy footsteps, and there must have been horses in the courtyard outside the house; she could hear their hoofs on the cobbles. Once too she heard the stable clock strike three.

And dimly, in the back of her mind, something whispered, "He will be waiting for me on the spit of sand, and I am lying here, and I cannot move, and I cannot go to him," and she tried to raise herself from her bed, but she had no strength. It was still dark, while outside her window she could hear a little thin trickle of rain. Then she must have slept, the heavy dull sleep of exhaustion, for when she opened her eyes it was daylight, and the curtains had been drawn, and there was Harry kneeling by her side, fondling her hair with his great clumsy hands. He was peering into her face, his blue eyes troubled, and he was blubbing like a child.

"Are you all right, Dona?" he said, "are you better, are you well?"

She stared at him without understanding, the dull ache still behind her eyes, and she thought how ridiculous it was that he should kneel there, in so foolish a manner, and she felt a sort of shame upon her that he should do so.

"Rock's dead," he said. "We found him dead there, on the floor, with his poor neck broken. Rock, the best friend I have ever had." And the tears rolled down his cheeks, and she went on staring at him. "He saved your life, you know," said Harry; "he must have fought that devil single-handed, alone there in the darkness, while you fled up here to warn us. My poor beautiful, my poor sweet."

She did not listen to him any more, she sat up, looking at the daylight as it streamed into her window. "What is the time?" she said, "how long has the sun been risen?"

"The sun?" he said blankly, "why, it's nearly noon I believe. What of it? You are going to rest, are you not? You must, after all you have suffered last night."

She put her hands over her eyes and tried to think. It was noon then, and the ship would have sailed, for he could not have waited for her after the day had broken. She had lain here sleeping on her bed, while the little boat put in to the spit of sand and found it empty.

"Try and rest again, my lovely," said Harry, "try and forget the confounded God-damned night. I'll never drink again, I swear it. It's my fault, I ought to have stopped it all. But you shall have your revenge, I promise you that. We've caught him, you know, we've got the blasted fellow."

"What do you mean?" she said slowly, "what are you talking about?"

"Why, the Frenchman of course," he said, "the devil who killed Rock, and would have killed you too. The ship's gone, and the rest of his battered crew, but we've got him, the leader, the damned pirate."

She went on staring at him without understanding, dazed, as though he had struck her, and he, seeing her eyes, was troubled, and began once more to fondle her hair and to kiss her fingers, murmuring, "My poor girl, what a confounded to-do, eh, what a night, what a devilish thing." And then, pausing a moment, he looked at her, and flushed, a little confused, still holding her fingers, and because the despair in her eyes was something dark and new, was a thing he did not understand, he said to her awkwardly, like a shy and clumsy boy: "That Frenchman, that pirate, he didn't molest you in any way, did he, Dona?"

Chapter XXI

Two DAYS CAME and went, things without hours or minutes, in which she dressed herself, and ate, and went out into the garden, and all the while she was possessed by a strange sense of unreality, as though it was not she who moved, but some other woman, whose very words she did not understand. No thoughts came to her mind: it was as though part of her slept still, and the numbness spread from her mind to her body, so that she felt nothing of the sun when it came from two clouds and shone a moment, and when a little chill wind blew she was not cold.

At one time the children ran out to greet her, and James climbed on her knee, and Henrietta, dancing before her, said, "A wicked pirate has been caught, and Prue says he will be hanged." She was aware of Prue's face, pale, rather subdued, and with an effort she remembered that there had been death, of course, at Navron, that at this moment Rockingham would be lying in a darkened church awaiting burial. There was a dull greyness about these days, like the Sundays she remembered as a child, when the Puritans forbade dancing on the green. There was a moment when the rector of Helston Church appeared and spoke to her gravely, condoling with her on the loss of so great a friend. And afterwards he rode away, and Harry was beside her again, blowing his nose, and speaking in a hushed voice entirely unlike himself. He stayed by her continually, humble and anxious to please, and kept asking her whether she needed anything, a cloak, or a coverlet for her knees, and when she shook her head, wishing he would leave her quietly, so that she could sit, staring at nothing, he began protesting once more how much he loved her, and that he would never drink again: it was all because he had drunk too much that fatal night that they had let themselves be trapped in such a way, and but for his carelessness and sloth poor Rockingham would be alive.

"I'll cut out gambling too," he said. "I'll never touch another card, and I'll sell the town house, and we'll go and live in Hampshire, Dona, near your old home, where we first met. I'll live the life of a country gentleman at last, with you and the children, and I'll teach young James to ride and to hawk. How would you like that, eh?"

Still she did not answer, but went on staring in front of her.

"There's always been something baleful about Navron," he said, "I remember thinking so as a boy. I never felt well here: the air is too soft. It doesn't suit me. It doesn't suit you, either. We'll go away as soon as this business is over and done with. If only we could lay our hands on that damned spy of a servant, and hang 'em both at the same time. God, when I think of the danger you were in, you know, trusting that fellow." And he began to blow his nose again, shaking his head. One of the spaniels came fawning up to her, licking her hands, and suddenly she remembered the furious barking of the night, the yapping, the excitement, and in a flash her darkened mind became alive again, awake and horribly aware. Her heart beat loudly, for no reason, and the house, and the trees, and the figure of Harry sitting beside her took shape and form. He was talking, and she knew now that every word he uttered might be of importance, and that she must miss nothing, for there were plans to make, and time itself was now of desperate value.

"Poor Rock must have outwitted the servant from the first," he was saying. "There were signs of the struggle in his room, you know, and a trail of blood leading along the passage, and then it stopped suddenly, and we found no trace of the fellow. Somehow he must have got away, and perhaps have joined those other rascals on the ship, though I think it doubtful. They must have used some part of the river time and again as a sneak-hole. By thunder, Dona, if we'd only known."

He smote his fist in the palm of his hand, and then, remembering that Navron had been a house of death and that to talk loudly, or to swear, was to show irreverence towards the dead, he lowered his voice, and sighed, and said, "Poor Rock. I hardly know how we shall do without him you know."

She spoke at last, her voice sounding strange to her own ears, because her words were careful, like a lesson learnt by heart.

"How was he caught?" she said, and the dog was licking her hand again, but she did not feel it.

"You mean that damned Frenchman?" said Harry, "well, we-we rather hoped you could tell us a bit about it, the first part, because you were with him, weren't you, in the salon there. But I don't know, Dona, you seemed so stunned and strange when I asked you. I said to Eustick and the others, 'Hell, no, she's been through too much,' and if you'd rather not tell me about it, well, that's all there is to it, you know."

She folded her hands on her lap and she said, "He gave me back my ear-rings and then he went."

"Oh, well," said Harry, "if that was all. But then he must have come back, you know, and tried to follow you upstairs. Perhaps you don't remember fainting there, on the passage by your room. Anyway, Rock must have been there by then, and guessing what the scoundrel was after, threw himself on the fellow, and in the fight that followed-for your safety Dona, you must always remember that-he lost his life, dear staunch friend that he was."

Dona waited a moment, watching Harry's hand as he stroked the dog.

"And then?" she said, looking away from him, across the lawn.

"Ah, the rest we owe to Rock too. It was his plan, from the first. He suggested it to Eustick and George Godolphin when we met them at Helston. 'Have your men posted on the beaches,' he said, 'and boats in readiness, and if there is a vessel hiding up the river, you'll get her as she comes down by night, on the top of the tide.' But instead of getting the ship, we got the leader instead."

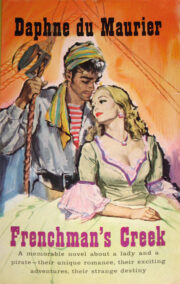

"Frenchman’s Creek" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Frenchman’s Creek". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Frenchman’s Creek" друзьям в соцсетях.