"A curious fever," he said, ignoring her words, "that leaves the patient with gypsy coloring and eyes so large. You did not see a physician, it seems?"

"I was my own physician."

"With the advice of the excellent William. What an unusual accent he has, by-the-way. Quite a foreign intonation."

"All Cornishmen speak likewise."

"But I understand he is not a Cornishman at all, at least so the groom informed me in the stable this morning."

"Perhaps he is from Devon then. I have never questioned William about his ancestry."

"And it seems that the house was entirely empty until you came? The unusual William took the responsibility of Navron upon his shoulders with no other servants to help him."

"I did not realise you engaged in stable gossip, Rockingham."

"Did you not, Dona? But it is one of my favourite pastimes. I always learn the latest scandals in town from the servants of my friends. The chatter of back-stairs is invariably true, and so extremely entertaining."

"And what have you learnt from the back-stairs at Navron?"

"Sufficient, dear Dona, to pique the curiosity."

"Indeed?"

"Her ladyship, I understand, has a passion for long walks in the heat of the day. She takes a joy, it seems, in wearing the oldest clothes, and returning, sometimes, be-splashed with mud and river water."

"Very true."

"Her ladyship's appetite is fitful, it appears. Sometimes she will sleep until nearly midday, and then demand her breakfast. Or she will taste nothing from noon until ten o'clock at night, and then, when her servants are abed, the faithful William brings her supper."

"True again."

"And then, after having been in the rudest of health, she unaccountably takes to her bed, and shuts her door upon her household, even upon her children, because it seems she suffers from a fever, although no physician is sent for, and once again the unusual William is the only person admitted within her door."

"And what more, Rockingham?"

"Oh, nothing more, dear Dona. Only that you seem to have recovered very quickly from your fever, and show not the slightest pleasure in seeing your husband or his closest friend."

There was a sigh, and a yawn, and a stretching of limbs, and Harry threw his handkerchief from his face and scratched his wig.

"God knows that last remark you made was true enough," he said, "but then Dona always was an iceberg, Rock, old fellow; I have not been married to her for close on six years without discovering that! Damn these flies! Hi, Duchess, catch a fly. Stop 'em from plaguing your master, can't you?" And sitting up he waved his handkerchief in the air, and the dogs woke up and jumped and yapped, and then the children appeared round the corner of the terrace for their half-hour's romp before bed-time.

It was just after six when a shower sent them indoors, and Harry, still yawning and grumbling about the heat, sat down with Rockingham to play piquet. Three hours and a half yet until supper, and La Mouette still at anchor in the creek.

Dona stood by the window, tapping her fingers on the pane, and the summer shower fell heavy and fast. The room was close, smelling already of the dogs, and the scent that Harry sprinkled on his clothes. Now and again he burst into a laugh, gibing at Rockingham for some mistake or other in their game. The hands of the clock crept faster than she wished, making up now for the slowness of the day, and she began to pace up and down the room, unable to control her growing premonition of defeat.

"Our Dona seems restless," observed Rockingham, glancing up at her from his cards, "perhaps the mysterious fever has not entirely left her?"

She gave him no answer, pausing once more by the long window.

"Can you beat the knave?" laughed Harry, throwing a card down upon the table, "or have you lost again? Leave my wife alone, Rock, and attend to the game. Look you there, there's another sovereign gone into my pocket. Come and sit down, Dona, you are worrying the dogs with your infernal pacing up and down."

"Look over Harry's shoulder, and see if he is cheating," said Rockingham, "time was when you could beat the pair of us at piquet."

Dona glanced down at them, Harry loud and cheerful, already a little flushed with the drink he had taken, oblivious to everything but the game he was playing, and Rockingham humouring him as he was wont to do, but watchful still, like a sleek cat, his narrow eyes turned upon Dona in greed and curiosity.

They were set there though, for another hour at least, she knew Harry well enough for that, and so yawning, and turning from the window, she began to walk towards the door.

"I shall lie down until supper," she said. "I have a headache. There must be thunder in the air."

"Go ahead, Rock old boy," said Harry, leaning back in his chair, "I'll wager you don't hold a heart in your hand. Will you increase your bid? There's a sportsman for you. Fill up my glass, Dona, as you're up. I'm as thirsty as a crow."

"Don't forget," said Rockingham smiling, "that we may have work to do before midnight."

"No, by the Lord, I have not forgotten. We're going to catch the froggie, aren't we? What are you staring at me for, my beautiful?"

He looked up at his wife, his wig a little askew, his blue eyes filmy in his handsome florid face.

"I was thinking, Harry, that you will probably look like Godolphin in about ten years' time."

"Were you, damme? Well, and what of it? He's a stout fellow, is George Godolphin, one of my oldest friends. Is that the ace you're holding in front of my face? Now God damn you for a blasted cheat and a robber of innocent men."

Dona slipped from the room, and going upstairs to her bedroom she shut the door, and then pulled the heavy bell-rope that hung beside the fireplace. A few minutes later someone knocked, and a little maid-servant came into the room.

"Will you please send William to me," said Dona.

"I am sorry, my lady," said the girl, with a curtsy, "but William is not in the house. He went out just after five o'clock and he has not returned."

"Where has he gone?"

"I have no idea, my lady."

"It does not matter then, thank you."

The girl left the room, and Dona threw herself down on her bed, her hands behind her head. William must have had the same idea as herself. He had gone to see what progress had been made upon the ship, and to warn his master that his enemies would be supping at Navron this very night. Why did he delay though? He had left the house at five and it was now nearly seven.

She closed her eyes, aware in the stillness of her quiet room that her heart was thumping now as it had done once before, when, standing on the deck of La Mouette, she had waited to go ashore in Lantic bay. She remembered the chilled cold feeling she had had, and how, when she had gone below to the cabin, and eaten and drunk a little, the fear and the anxiety left her, and she had been filled with the glow of adventure. To-night though it was different. Tonight she was alone, and his hand was not in hers, and his eyes had not spoken to her. She was alone, and must play hostess to his enemies.

She went on lying there on her bed, and outside the rain fell away to a drizzle and ceased, and the birds began to sing, but still William did not come. She got up and went to the door and listened. She could hear the low murmur of the men's voices from the salon, and once Harry laughed and Rockingham too, and then they must have continued with their playing of piquet, for there came only the murmur again, and Harry swearing at one of the dogs for scratching. Dona could wait no longer. She wrapped a cloak around her, and stole downstairs into the great hall on tip-toe, and went out by the side-door into the garden.

The grass was wet after the rain, there was a silver sheen upon it, and there was a warm damp smell in the air like an autumn mist.

The trees dripped in the wood, and the little straggling path that led to the creek was muddied and churned. It was dark in the wood too, for the sun would not return now after the rain, and the heavy green foliage of midsummer made a pall over her head. She came to the point where the path broke off and descended rapidly, and she was about to turn leftwards as usual down to the creek when some sound made her pause suddenly, and hesitate, and she waited a moment, her hand touching the low branch of a tree. The sound was that of a twig snapping under a foot, and of someone moving through the bracken. She stood still, never moving, and presently, when all was silent again she looked over the branch that concealed her, and there, some twenty yards away, a man was standing, with his back to a tree, and a musket in his hands.

She could see the profile under the three-cornered hat, and the face was one she did not recognise, and did not know, but he stood there, waiting, peering down towards the creek.

A heavy rain-drop fell upon him from the tree above, and taking off his hat he wiped his face with his handkerchief, turning his back to her as he did so, and at once she moved away from the place where she had stood, and ran homewards along the path by which she had come. Her hands were chilled, and she drew her cloak more closely about her shoulders, and that, she thought, that is the reason why William has not returned, for either he has been caught and held, or he is hiding in the woods, even as I hid just now. For where there is one man there will be others, and the man I have just seen is not a native of Helford, but belongs to Godolphin, to Rashleigh, or to Eustick. And so there is nothing I can do, she thought, nothing but return to the house, and go up to my room, and dress myself, and put on my ear-rings and my pendants and my bracelets, and descend to the dining-hall with a smile on my lips, and sit at the head of the table with Godolphin on my right and Rashleigh on my left, while their men keep a watch here in the woods.

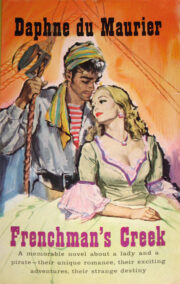

"Frenchman’s Creek" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Frenchman’s Creek". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Frenchman’s Creek" друзьям в соцсетях.