"Look, she's helpless," cried a voice, "the tide is taking her to the rocks, they must be mad aboard, or dead drunk, all of them."

"Why doesn't he wear ship and get up, out of it," shouted another, and "Look, the tide has her," came the answer, and someone else, shrieking in Dona's ear, "The tide is stronger than the wind yet, the tide has her every time."

Some of the men were struggling now with the boats moored beneath the quay, she could hear them swear as they fumbled with a frape, and Rashleigh and Godolphin, peering down from the side of the quay, cursed them for the delay. "Someone's monkey'd here with the frape," shouted one of the men, "the rope is parting, someone must have cut it with a knife," and suddenly Dona had a vision of little Pierre Blanc, grinning to himself in the darkness, while the great bell clanged and jangled on the quay.

"Swim, one of you," yelled Rashleigh, "swim and bring me a boat. By God, I'll thrash the fellow who played the trick, I'll have him hanged."

Now the ship was coming closer, Dona could see the men on the yards, and the great topsail shaking out, and someone was at the wheel there giving orders, someone with head thrown back, watching the sail draw taut.

"Ahoy, there! Ahoy!" yelled Rashleigh, and Godolphin too added his cry, "Wear ship, man, wear ship before you lose your chance."

And still the Merry Fortune held to her course; straight down channel and across the harbour she came, the ebbtide ripping under her keel. "He's crazy," screamed someone, he's making for the harbour mouth, look there, all of you, look there." For now that the ship was within hail Dona could see that there were three boats out in a line abreast, with a warp from the ship to each of them, and every man in them bent double to his oars, and still the topsail filled and pulled, and the courses too, and the ship heeled to a great puff of wind that came from the hills behind the town.

"He is going to sea," shouted Rashleigh, "by God, he is taking her to sea," and suddenly Godolphin turned, and his great bulbous eyes fell upon Dona, who in her excitement had crept close to the edge of the quay. "There's that boy," he called, "he is to blame for this, catch him, one of you, catch that boy there." Dona turned, ducking swiftly under the arm of an old man who stared at her blankly, and she began to run, blindly, away from the quay and straight up the lane past Rashleigh's house, away from the church, and the town, towards the cover of the hills, while behind her she could hear a man shouting, and the sound of running feet, and a voice calling "Come back, will you, come back, I say."

There was a path to her left, winding amongst the gorse and the young bracken, and she took it, stumbling on the rough ground in her clumsy shoes, the rain streaming in her face, and down below her she caught a gleam of the harbour water and could hear the wash of the tide against the cliff wall.

Her only thought was to escape, to hide herself from those questing, bulbous eyes of Godolphin, for Pierre Blanc was lost to her now, and the Merry Fortune fighting her own battle in mid-harbour.

She ran on in the wind and the darkness, the path taking her along the side of the hill to the harbour mouth, and even now it seemed to her that she could hear the hideous clanging of the ship's bell on the quay, rousing the people of the town, and she could see the angry figure of Philip Rashleigh hurling curses upon the men who struggled with the frape. The path began to descend at last, and pausing in her headlong flight, and wiping the rain from her face, she saw that it led down to a cove by the harbour mouth, and then wound upwards again to the fort on the headland. She stared in front of her, listening to the sound of the breakers below, and straining her eyes for a glimpse of the Merry Fortune, and then, glancing back over her shoulder, she saw a pin-prick of light advancing towards her down the path, and she heard the crunch of footsteps.

She flung herself down amongst the bracken, and the footsteps drew nearer, and she saw it was a man bearing a lantern in his hand. He walked swiftly, looking neither to right nor left of him, and he went straight past her, down to the cove, and then up again towards the headland; she could see the glimmer of his lantern as he climbed the hill. She knew then that he was going to the fort, Rashleigh had sent him to warn the soldiers on duty at the fort. Whether suspicion had crossed his mind at last, or whether he still thought that the master of the Merry Fortune had lost his wits and was taking his ship to disaster, she could not tell, nor did it matter very much. The result would be the same. The men who guarded the entrance to the harbour would fire on the Merry Fortune.

And now she ran down the path to the cove, but instead of climbing to the headland as the man with the lantern was doing, she turned left along the beach, scrambling over the wet rocks and the seaweed to the harbour mouth itself. It seemed to her that she was looking once again at the plan of Fowey Haven. She saw the narrow entrance, and the fort, and the ridge of rocks jutting out from the cove where she now found herself, and in her mind was the one thought that she must reach those rocks before the ship came to the harbour mouth, and in some way warn the Frenchman that the alarm had been sent to the fort.

She was sheltered momentarily, under the lee of the headland, and no longer had to fight her way against the wind and the rain, but her feet slipped and stumbled on the slippery rocks, still running wet where the tide had left them, and there were cuts on her hands and her chin where she had fallen, while the hair that had come loose from the sash that bound it blew about her face.

Somewhere a gull was screaming. Its persistent cry echoed in the cliffs above her head, and she began to curse it, savagely and uselessly, for it seemed to her that every gull now was a sentinel, hostile to herself and to her companions, and this bird who wailed in the darkness was mocking her, crying that all her attempts to reach the ship were useless. In a moment or two the ridge of rocks would be within reach, she could hear the breakers, and then, raising herself on her hands and looking forward, she saw the Merry Fortune bearing down towards the harbour mouth, the short seas breaking over her bows. The boats that had towed her were hoisted now on deck, and the men that had manned them were thronging the ship's side, for suddenly and miraculously the wind had shifted a point or two to the west, and with the strong ebb under her the Merry Fortune was sailing her way sea-ward. There were other boats upon the water now, little craft coming in pursuit, and men who shouted and men who swore, and surely that was Godolphin himself in one of them, with Rashleigh by his side. Dona laughed, wiping her hair out of her eyes, for nothing mattered now, neither Rashleigh's anger nor Godolphin's recognition of her should it come, for the Merry Fortune was sailing away from them, recklessly and joyfully, into the summer gale. Once again the gull screamed, and this time he was close to her; she looked about for a stone to throw at him, and instead she saw a small boat shoot past the ridge of rocks ahead of her, and there was Pierre Blanc, his small face upturned towards the cliffs, and once again he gave his sea-gull's cry.

Dona stood then, laughing still, and raised her arms above her head, and shouted to him, and he saw her and brought his boat in to the rocks beside her, and she scrambled down into the boat beside him, asking no question, nor he either, for he was pulling now into the short breaking seas towards the ship. The blood was running from the cut on her chin, and she was soaked to the waist, but she did not care. The little boat leapt into the steep seas, and the salt spray blew in her face with the wind and the rain. There was a flash of light, and the crash of a cannon, and something splashed into the water ten yards ahead of them, but Pierre Blanc, grinning like a monkey, pulled on into mid-channel, and here was the Merry Fortune herself, thrashing through the sea towards them, the wind thundering in her crowded sails.

Another flash, another deafening report, and this time there was a tearing sound of splintering wood, but Dona could see nothing, she only knew that someone had thrown a rope down into the boat, and someone was pulling them close to the side of the ship, and there were faces laughing down at her, and hands that lifted her, and away beneath her was the black swirl of water and the little boat upside down, disappearing in the darkness.

The Frenchman was standing at the wheel of the Merry Fortune, and he too had a cut on his chin, and his hair was blowing about his face, and the water streamed from his shirt, but for one moment his eyes held hers and they smiled at each other, and then "Throw yourself on your face, Dona," he said, "they'll be firing again," and she lay beside him on the deck, exhausted, aching, shivering with the rain and the spray, but nothing mattered, and she did not mind.

This time the shot fell short. "Save your powder, boys," he laughed, "you'll not catch us this time," while little Pierre Blanc, streaming wet and shaking himself like a dog, leant over the ship's side, his finger to his nose. And now the Merry Fortune reared and fell into the trough of the seas, and the sails thundered and shook, while someone shouted from the pursuing boats behind, and someone with a musket in his hand let fly at the rigging.

"There is your friend, Dona," called the Frenchman, "do you know if he shoots straight?" She crawled aft, looking over the stern rail, and there was the leading boat almost beneath them, with Rashleigh's face glaring up at them, and Godolphin raising a musket to his shoulder.

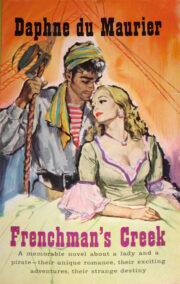

"Frenchman’s Creek" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Frenchman’s Creek". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Frenchman’s Creek" друзьям в соцсетях.