She would not tell him immediately, for the fun of teasing him, and coming into the room, casting her kerchief from her head, she said, "I have been walking, William, my head is better."

"So I observe, my lady," he said, his eyes upon her.

"I walked by the river, where it is quiet and cool."

"Indeed, my lady."

"I had no knowledge of the creek before. It is enchanting, like a fairy-tale. A good hiding-place, William, for fugitives like myself."

"Very probably, my lady."

"And my Lord Godolphin, did you see him?"

"His lordship was not at home, my lady. I bade his servant give your flowers and the message to his lady."

"Thank you, William." She paused a moment, pretending to arrange the sprigs of lilac in their vase, and then, "Oh, William, before I forget. I am giving a small supper party to-morrow night. The hour is rather late, ten o'clock."

"Very well, my lady. How many will you be?"

"Only two, William. Myself and one other-a gentleman."

"Yes, my lady."

"The gentleman will be coming on foot, so there is no need for the groom to stay up and mind a horse."

"No, my lady."

"Can you cook, William?"

"I am not entirely ignorant of the art, my lady."

"Then you shall send the servants to bed, and cook supper for the gentleman and myself, William."

"Yes, my lady."

"And you need not mention the visit to anyone in the house, William."

"No, my lady."

"In fact, William, I propose to behave outrageously."

"So it would seem, my lady."

"And you are dreadfully shocked, William?"

"No, my lady."

"Why not, William?"

"Because nothing you or my master ever did could possibly shock me, my lady."

And at this she burst out laughing, and clasped her hands together.

"Oh, William, my solemn William, then you guessed all the time! How did you know, how could you tell?"

"There was something about your walk, as you entered just now, my lady, that gave you away. And your eyes were — if I may say so without giving offence-very much alive. And coming as you did from the direction of the river I put two and two together, as it were, and said to myself: 'It has happened. They have met at last.' "

"Why 'at last,' William?"

"Because, my lady, I am a fatalist by nature, and I have always known that, sooner or later, the meeting was bound to come about."

"Although I am a lady of the manor, married and respectable, with two children, and your master a lawless Frenchman, and a pirate?"

"In spite of all those things, my lady."

"It is very wrong, William. I am acting against the interests of my country. I could be imprisoned for it."

"Yes, my lady."

But this time he hid his smile no longer, his small button mouth relaxed, and she knew he would no longer be inscrutable and silent, but was her friend, her ally, and she could trust him to the last.

"Do you approve of your master's profession, William?" she said.

"Approve and disapprove are two words that are not in my vocabulary, my lady. Piracy suits my master, and that is all there is to it. His ship is his kingdom, he comes and goes as he pleases, and no man can command him. He is a law unto himself."

"Would it not be possible to be free, to do as he pleases, and yet not be a pirate?"

"My master thinks not, my lady. He has it that those who live a normal life, in this world of ours, are forced into habits, into customs, into a rule of life that eventually kills all initiative, all spontaneity. A man becomes a cog in the wheel, part of a system. But because a pirate is a rebel, and an outcast, he escapes from the world. He is without ties, without man-made principles."

"He has the time, in fact, to be himself."

"Yes, my lady."

"And the idea that piracy is wrong, that does not worry him?"

"He robs those who can afford to be robbed, my lady. He gives away much of what he takes. The poorer people in Brittany benefit very often. No, the moral issue does not concern him."

"He is not married, I suppose?"

"No, my lady. Marriage and piracy do not go together."

"What if his wife should love the sea?"

"Women are apt to obey the laws of nature, my lady, and produce babies."

"Ah! very true, William."

"And women who produce babies have a liking for their own fireside, they no longer want to roam. So a man is faced at once with a choice. He must either stay at home and be bored, or go away and be miserable. He is lost in either case. No, to be really free, a man must sail alone."

"That is your master's philosophy?"

"Yes, my lady."

"I wish I were a man, William."

"Why so, my lady?"

"Because I too would find my ship, and go forth, a law unto myself."

As she spoke there came a loud cry from upstairs, followed by a wail, and the sound of Prue's scolding voice. Dona smiled, and shook her head. "Your master is right, William," she said, "we are all cogs in a wheel, and mothers most especially. It is only the pirates who are free." And she went upstairs to her children, to soothe them, and wipe away their tears. That night, as she lay in bed, she reached for the volume of Ronsard on the table by her side, and thought how strange it was that the Frenchman had lain there, his head upon her pillow, this same volume in his hands, his pipe of tobacco in his mouth. She pictured him laying aside the book when he had read enough, even as she did now, and blowing out the candle, and then turning on his side to sleep. She wondered if he slept now, in that cool, quiet cabin of his ship, with the water lapping against the side, the creek itself mysterious and hushed. Or whether he lay on his back as she did, eyes open in the darkness and sleep far distant, brooding on the future, his hands behind his head.

Next morning, when she leant from her bedroom and felt the sun on her face, and saw the clear bright sky with a sharp gloss about it because of the east wind, her first thought was for the ship in the creek. Then she remembered how snug was the anchorage, tucked away in the valley, shrouded by the trees, and how they could scarce have knowledge there of the turbulent tide ripping up the parent river, the short waves curling, while the steep seas at the mouth of the estuary reared and broke themselves into spray.

She remembered the evening that was to come, and the supper party, and began to smile, with all the guilty excitement of a conspirator. The day itself seemed like a prelude, a foretaste of things to come, and she wandered out into the garden to cut flowers, although those in the house were not yet faded.

The cutting of flowers was a peaceful thing, soothing to her unquiet mind, and the very sensation of touching the petals, fingering the long green stalks, laying them in a basket, and later placing them one by one in the vases that William had filled for her, banished her first restlessness. William too was a conspirator. She had observed him in the dining-hall, cleaning the silver, and he had glanced up at her in understanding, for she knew why he worked with such ardour.

"Let us do full justice to Navron," she said; "bring out all the silver, William, and light every candle. And we will use that dinner service with the rose border that is shut away for banquets." It was exciting, it was amusing-she fetched the dinner service herself and washed the plates, dusty with disuse, and she made a little decoration in the centre of the table with the young buds of fresh-cut roses. Then she and William descended together to the cellar, and peered by candle-light at the cobweb-covered bottles, and he brought forth a wine greatly prized by his master, which they had not known was there. They exchanged smiles, they whispered furtively, and Dona felt all the lovely wickedness of a child who does something wrong, something forbidden, and chokes with secret laughter behind his parent's back.

"What are we going to eat?" she said, and he shook his head, he would not tell. "Rest easy, my lady," he said. "I will not disappoint you," and she went out into the garden once more, singing, her heart absurdly gay. The hot noon passed, hazy with the high east wind, and the long hours of afternoon, and tea with the children under the mulberry tree, and so round to early evening once again, and their bed-time, and a ceasing of the wind, while the sun set, the sky glowed, and the first stars shone.

The house was silent once more, and the servants, believing her to be weary, to be retiring supperless to bed, congratulated themselves on the easiness of their mistress, and took themselves to their own quarters. Somewhere, alone in his room no doubt, William prepared the supper. Dona did not ask. It did not matter.

She went to her own room, and stood before her wardrobe, pondering which gown to wear. She chose one cream-coloured, which she had worn often, and which she knew became her well, and she placed in her ears the ruby earrings that had belonged to Harry's mother, and round her throat the ruby pendant.

"He will not notice," she thought, "he is not that sort of person, he does not care about women, or their clothes, or their jewels," and yet she found herself dressing with great care, combing her ringlets round her fingers and setting them behind her ears. Suddenly she heard the stable clock strike ten, and in a panic she laid the comb aside, and went downstairs. The staircase led direct into the dining-hall, and she saw that William had lighted every candle, even as she had told him, and the bright silver shone on the long table. William himself was standing there, arranging dishes on the sideboard, and she went to see what it was he had prepared. Then she smiled. "Oh, William, now I know why you went down to Helford this afternoon, returning with a basket." For there on the sideboard was crab, dressed and prepared in the French fashion, and there were small new potatoes too, cooked in their skins, and a fresh green salad sprinkled with garlic, and tiny scarlet radishes. He had found time too to make pastry. Thin, narrow wafers, interlaid with cream, while next to them, alone in a glass bowl, was a gathering of the first wild strawberries of the year.

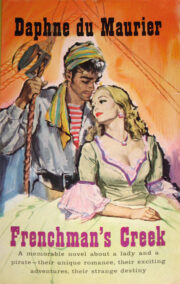

"Frenchman’s Creek" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Frenchman’s Creek". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Frenchman’s Creek" друзьям в соцсетях.