“What’s the matter, Amber? What’ve I done? What’s got into you?”

Angrily she wrenched her hand free and ran out. For she now felt herself above such trifling with men of Tom Andrews’ station and was only eager to get upstairs and into bed where she could lie and think of Lord Carlton and dream of tomorrow.

The kitchen was deserted except for Sarah, sweeping the flagstoned floor one last time before going to bed. There were three or four rushlights burning, a circle of tiny moths darting about each tenuous reaching flame, and only the bell-like song of the crickets invaded the evening stillness. Matt came in, scowling, and without a word went to the barrel of ale which stood in a far cool corner of the room, poured himself a pewter mugful and drank it off. He was a middle-sized serious man who worked hard and made a good living and loved his family. And he was conscientious and God-fearing, with strong beliefs as to what was right and what was wrong, what was good and what was bad.

Sarah gave him a glance. “What is it, Matt? Is the foal worse?”

“No, she’ll live, I think. It’s that girl.”

His face was sour and now he went to stand before the great fireplace which was surrounded on all sides with blackened pots and pans, gleaming copper, pewter polished till it looked like silver. Bacon and hams, in great nets, hung from the overhead beams, and there were several thick tied-up bunches of dry herbs.

“Who?” asked Sarah. “Amber?”

“Who else? Not an hour since I saw her come out of the dairy and a minute later Tom Andrews followed her, looking like a whipped pup. She’s got the boy half out of his noddle—he’s all but useless to me. And what was she doing, pray, down at the inn with a pack of gentlemen?” His voice rose angrily.

Sarah went to stand the broom just outside the door and then closed it, throwing the bolt. “Hush, Matt! Some of the men are still in the parlour. I don’t think she was doing anything she shouldn’t have. She was just passing by and saw them—it’s natural she should stop.”

“And come home alone in the dark? Did it take her an hour to hear that the King’s to return? I tell you, Sarah, she’s got to get married! I won’t have her disgracing my family! D’ye hear me?”

“Yes, Matt, I hear you.” Sarah went to the cradle beside the fireplace where the baby had begun to stir and whimper, took him out and put him to her breast, then she went to sit down on the settle. She gave a weary little sigh. “Only she don’t want to get married.”

“Oh!” said Matt sarcastically. “So she don’t want to get married! I suppose Jack Clarke or Bob Starling’s not good enough for ’er—two of the finest young fellows in Essex.”

Sarah smiled gently, her voice soft and tired. “After all, Matt, she is a lady.”

“Lady! She’s a strumpet! For four years now she’s caused me nothing but trouble, and by the Lord Harry I’m fed up to the teeth! Her mother may have been a lady but she’s a—”

“Matt! Don’t speak so of Judith’s child. Oh, I know, Matt. It troubles me too. I try to warn her—but I don’t know what heed she pays me. Agnes told me tonight—Oh, well, I don’t think it means anything. She’s pretty and the girls are jealous and I suppose they make up tales.”

“I’m not so sure it’s just tale-telling, Sarah! You’ve always got a mind to think the best of folks—but they don’t always deserve it. Bob Starling asked me for her again today, and I tell you if she an’t married soon not even Tom Andrews ’ll have her, dowry or no!”

“But suppose her father comes, and finds her married to a farmer. Oh, Matt, sometimes I think we’re not doing the right thing—not telling her who she is—”

“What else can we do, Sarah? Her mother’s dead. Her father’s dead, too, or we’d have heard some word of him—and we’ve never found trace of the other St. Clares. I tell you, Sarah, she’s got no choice but to marry a farmer and for her to know she’s of the quality—” He made a gesture with his hands. “God forbid! The fellow who gets her ’s got my pity as ‘tis. Why make it any the worse for ’im? Now, don’t give me any more excuses, Sarah. It’s Jack Clarke or Bob Starling, one or t’other, and the sooner the better—”

CHAPTER TWO

IN their painted blue and red wagons, on foot and on horseback, every farmer and cottager within a twenty-mile radius converged upon Heathstone. With him he brought his wife and children, the corn and wheat and livestock he had to sell and the linens or woollens woven by the women during long winter evenings. But he came to buy also. Shoes and pewter-plates and implements for the farm, as well as many things he did not need but which it would please him to have: toys for the children, ribbons for his daughters’ hair, pictures for the house, a beaver hat for himself.

Booths were set up on the green about the old Saxon cross, making lanes which swarmed with people in their holiday dress—full breeches and neck-ruffs and long-sleeved gowns—all many years out of the style but nevertheless kept carefully in wardrobes from one great occasion to the next. Drums beat and fiddles played. The owners of the booths bawled out their wares in voices which were already growing hoarse. Curious crowds stood and stared, each face contorted with sympathy, to watch a sweating man have his rotten tooth pulled, while the dentist loudly proclaimed that the extraction was absolutely painless. There was a fire-eater and a stilt-walker, trained fleas and a contortionist, jugglers and performing apes, and a Punch and Judy show. Over one great tent flew a flag to announce that a play was in progress—but the Puritan influence remained strong enough so that the audience inside was a thin one.

Amber, standing between Bob Starling and Jack Clarke, frowned and tapped her foot as her eyes ran swiftly and impatiently over the crowd.

Where is he!

She had been there since seven o’clock, it was now after nine, and still she had seen no sign of Lord Carlton or his friends. Her stomach churned with nervousness, her hands were wet and her mouth dry. Oh, but sure, if he was coming at all he’d be here by now. He’s gone. He’s forgot all about me and gone on—

Jack Clarke, a tall blunt-faced young man, gave her a nudge. “Look, Amber. How d’ye like this?”

“What? Oh. Oh, yes, it’s mighty fine.”

She turned her head and searched the gleefully yelling group about the jack-pudding who stood on a stand, covered from head to foot with a mess of custard which had been thrown at him, so many farthings a custard.

Oh, why doesn’t he come!

“Amber—how d’ye like this ribbon—”

She gave them each a quick smile in turn, trying to drag her mind away from him, but she could not. He had been in her thoughts and heart every waking moment, and if she did not see him again today she knew she would never be able to survive the disappointment. No greater crisis had ever confronted her, and she thought she had met many.

She had dressed with extraordinary care and was sure that she had never looked prettier.

Her skirt, which did not quite reach her ankles, was made of bright green linsey-woolsey, caught up high in back to show a red-and-white-striped petticoat. She had pulled the laces of her black stomacher as tight as possible to display her little waist; and after leaving Sarah she had opened her white blouse down to the valley of her breasts. Wreathing the crown of her head was a garland of white daisies, their stems twisted together, and in one hand she carried a broad-brimmed straw bongrace.

Now, must all that trouble go to waste on a pair of dolts who stood hovering over her, jingling the coins in their pockets and glaring at each other?

“I think I like this—” She spoke absently, indicating a red satin ribbon which lay in the pile on the counter and then, frowning again, she turned her head—and saw him.

“Oh!”

For an instant she stood unmoving, and then suddenly she picked up her skirts and rushed off, leaving them to stare after her, bewildered and astonished. Lord Carlton, with Almsbury and one other young man, had just entered the fair grounds and were standing while an old vegetable woman knelt to wipe their boots according to the ancient custom. Amber got there out of breath but smiling and made them a curtsy to which they all replied by removing their hats and bowing gravely.

“Damn me, sweetheart!” cried Almsbury enthusiastically. “But you’re as pretty a little baggage as I’ve seen in the devil’s own time!”

“God-a-mercy, m’lord,” she said, thanking him. But her eyes went back instantly to Lord Carlton whom she found watching her with a look that made her arms and back begin to tingle. “I was afraid—I was afraid you were gone.”

He smiled. “The blacksmith had gone off to the Fair and we had to hammer out the shoe ourselves.” He glanced around. “Well—what do you think we should see first?”

In his eyes and the expression about his mouth was a kind of lazy amusement. It embarrassed her, made her feel helpless and tongue-tied and awkward, and a little angry too. For how was she to impress him if she could not think of anything to say, if he saw her turning first white and then red, if she stood and stared at him like a silly pea-goose?

The old woman had finished now and as each of the men gave her a coin to “pay his footing” she went on her way. But she looked back over her shoulder at Amber who was beginning to feel conspicuous, for everyone was watching the Cavaliers and, no doubt, wondering what business a country-girl might have with them. She would have been delighted by the attention but that she was afraid some of her relatives might see her—and she knew what that would mean. They must get away somehow, to a safer quieter place.

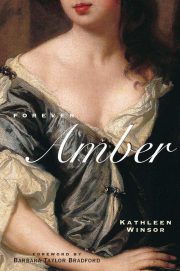

"Forever Amber" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Forever Amber". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Forever Amber" друзьям в соцсетях.