“Oh,” said Amber, suddenly crestfallen. “But I thought that Tunbridge Wells was frequented by persons of the best quality! My physician who sent me here told me that her Majesty was here with all her ladies only last summer.”

“Yes, I believe she was. But where there’s quality there are sure to be rooks. And it’s unworldly young persons like yourself of whom they’ll take the greatest advantage.”

While he talked Amber reached up to adjust the bow in her hair, as a signal for Nan who was waiting just outside and peeking in the window. “Oh!” she said, with a troubled frown, “how could I have been so foolish! I hope—”

At that moment Nan came in, out of breath, and stood in the doorway taking off her chopins. “Heavens, mam!” she cried excitedly. “The landlord at the inn refused the money! He says it’s a false coin!”

“A false coin! Why, that was one Mr. Kifflin gave me last night!”

Samuel Dangerfield turned in his chair. “May I see it?” He took it from Nan, rung it upon the table and felt of the edges while both women watched him. “It is a false one,” he said seriously. “So the young coxcombs are counterfeiters. That’s a sorry business—and a dangerous one. I wonder how many others they’ve got to change money with them?”

“Everyone who looked simple enough, I suppose!” said Amber indignantly. “Well, I think we should call the constable and put ’em where they belong!”

Mr. Dangerfield, however, was less inclined to be vindictive. “The laws are too harsh—they’d be hanged, drawn, and quartered.” That would not have troubled Amber but she thought it best not to say so. “I believe we can manage them some other way. Do you think, Mrs. St. Clare, that you could get them to come here on some pretext or other?”

“Why, they should be along any minute—they asked me to walk to the well with them.”

When they arrived, not much later, Nan opened the door. At sight of Mr. Dangerfield their mouths opened into broad grins—and then closed suddenly when he said: “Mrs. St. Clare and I have just been discussing the fact that there seem to be counterfeiters at Tunbridge.”

Kifflin raised his eyebrows. “Counterfeiters? Gad! It’s un thinkable! I swear the wretches grow bolder every day!”

While Wigglesworth exclaimed, as though he could not believe his own ears, “Counterfeiters at Tunbridge!”

“Yes,” said Amber. “I have a shilling that was just refused at the inn and Mr. Dangerfield says it’s not a true coin. Perhaps they’d like to see it, sir.”

He gave it to Wigglesworth and both young men examined it closely, frowning, while Kifflin cleared his throat. Their faces were beginning to shine with sweat.

“It looks good enough to me,” said Kifflin at last. “But then I’m such a simple fellow someone has always got me on the hip.”

Wigglesworth laughed, not very enthusiastically. “That’s exactly my case, to the letter.” He returned the coin.

“The constable,” said Mr. Dangerfield gravely, “will be along soon to look at this coin. If he finds it to be false I suppose he’ll examine every person in the village.”

At that moment a country girl went by outside carrying a basket over her arm and crying, “Fresh new eggs! Who’ll buy my new fresh eggs?”

Kifflin turned about quickly. “There she is, Will. I hope you’ll excuse us, Mrs. St. Clare, but we came to ask if we might wait upon you later in the day. We overslept and came out in search of some eggs for our dinner. Good-day, madame. Good-day, sir.”

He and Wigglesworth bowed, backed their way out of the room, and once outside turned and started off in all haste. Their pace increased, they passed the girl without giving her so much as a glance, and when they had gone two hundred yards broke into an open run and at last cut off the main street and disappeared from sight. Amber and Mr. Dangerfield, who had gone out to watch, looked at each other and then burst into laughter.

“Look at ’em go!” cried Amber. “I vow they won’t stop for breath till they’ve reached Paris!”

She shut the door again and gave a little sigh. “Well, I hope I’ve learnt my lesson. I vow I’ll never put my trust in strangers again.”

He was smiling down at her. “A young lady as pretty as you are should be suspicious of all strangers.” He said it with the air of a man who intends to be very gallant, without ever having had much practice. And when she answered the compliment with a quick upward slanting glance he cleared his throat and his ruddy face darkened. “Hem—I wonder, Mrs. St. Clare, if you’d care to put your trust in this stranger long enough to walk to the well with him?”

Confidence was beginning to sweep through Amber, and the intoxication she always felt when she knew a man was attracted to her. “Of course I would, sir. I think I know an honest man when I see him—even if I can’t always tell one who isn’t.”

Amber had acted in numerous plays depicting the rigid austere hypocritical life of the City families and, though all of them had been bitter and satirical and slanderously exaggerated, she had taken them for literal truth. Consequently, she thought she knew exactly what Samuel Dangerfield would admire in a woman; but she soon discovered that her own instinct was a surer guide.

For as she became better acquainted with him she began to realize that even though he was a City merchant and a Presbyterian he was nevertheless a man. And she found to her surprise that he bore no resemblance at all to the sanctimonious severe dour old humbugs who had occasioned such derisive laughter at His Majesty’s Theatre.

If he was not frivolous, neither was he grimly sober; his disposition was a happy one and he laughed easily. He had worked hard all his life, for he had accumulated most of that vast fortune himself, but he was all the more susceptible to a young woman’s gaiety now. His family life had been a close one, but that had given him perhaps a sense of loss, and of curiosity. Amber came into his life like a spring gale, fresh, invigorating, a challenge to whatever he had of dormant venturesomeness. She was everything he had never known before in a woman, and much he had scarcely suspected.

It was not long before they were spending hours out of every day together, and though Samuel insisted that she must grow bored with the company of an old man and urged her to become acquainted with the few young people who were there, Amber insisted that she hated young fellows who were always so silly and empty-headed and thought of nothing but dancing or gambling or going to the play. She kept in close and never went out when she could avoid it, for she was afraid that someone else might recognize her.

And she thought that she could guess pretty well what he would think of an actress, by his opinion of the Court in general. For one day, after some mention of King Charles, he said: “His Majesty could be the greatest ruler our nation has ever had but, unfortunately, not only for him but for all of us, the years of exile were his ruin. He learned a set of habits and a way of living during that time from which he can never escape—partly, I’m afraid, because he doesn’t want to.”

Amber, stitching on a piece of embroidery borrowed from Nan’s work-basket, observed soberly that she had heard Whitehall had grown a most wicked place.

“It is wicked. Wicked and corrupt. Honour is a sham, virtue a laughing-stock, marriage the butt for vulgar jests. There are still decent and honest men aplenty at Whitehall, as everywhere else in England—but knaves and fools elbow them aside.”

Most of their conversation, however, was less serious, and he seldom cared to discuss ethical or even political matters with her. Women were not interested in such things, and pretty ones least of all. Besides, she was his escape from them.

But Amber did often ask him to advise her about financial matters; and listened wide-eyed and with her head nodding every so often to his talk of interest and principal, mortgages, title-deeds, and revenue. She talked of her goldsmith and when she mentioned Shadrac Newbold’s name was glad to see how favourably impressed he seemed. She said that it was a great responsibility for her to handle her husband’s money—she represented herself as a rich young widow—and that she worried a great deal for fear someone would cheat her out of it. That was another reason, she said, why she was always suspicious of young men who wished to strike up an acquaintance. She also talked frequently about her family and what terrible things they had suffered in the Wars—recounting, with elaboration, tales she had heard from Almsbury about his own or Lord Carlton’s difficulties. By these devices she hoped to discourage him, had he been so inclined, from taking her for a fortune-hunter.

They played dozens of games of wit-and-reason, and she always let him win. She made him laugh with her mimicry of the fat middle-aged women and gouty old men who were there taking the waters. She played for him on her guitar and sang songs—not ribald street-ballads, but gay country tunes or the old English folk-songs: “Chevy Chase,” “Phillida Flouts Me,” “Highland Mary.” She pampered and flattered and teased him, treated him at all times as though he was much younger than he was, and yet was as solicitous for his comfort as if he had been much older. She guessed his age one day at forty-five and when he told her that his eldest son was thirty-five, insisted he could never make her believe that Banbury-story. She gave a lively imitation of a woman most thoroughly infatuated.

But at the end of three weeks he had not tried to seduce her and she was growing worried.

She stood at the window one evening just after he had gone and traced idle patterns on the frosted pane with her finger-nail. Her lower lip stuck out and there was a scowl on her forehead.

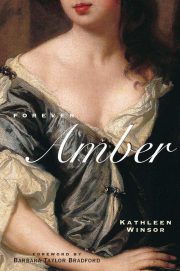

"Forever Amber" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Forever Amber". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Forever Amber" друзьям в соцсетях.