1644

THE SMALL ROOM was warm and moist. Furious blasts of thunder made the window-panes rattle and lightning seemed to streak through the room itself. No one had dared say what each was thinking—that this storm, violent even for mid-March, must be an evil omen.

As was customary for a lying-in chamber, the room had been largely cleared of its furniture. Now there remained only the bed with its tall head and footboards and linen side curtains, half a dozen low stools, and the midwife’s birth-stool, which had arm rests and a slanting back and cut-out seat. Beside the fireplace was a table with a pewter water-basin on it, brown cord and a knife, bottles and ointment-jars, and a pile of soft white cloths. Near the head of the bed was a very old hooded cradle, still empty.

The village women, all perfectly silent, stood close about the bed, watching what was happening there with tense, anxious faces. Sympathetic anguish, pity, apprehension, were the expressions they showed as their eyes shifted from the tiny red baby lying beside the woman who had just given it birth to the sweating midwife bending down and working with her hands beneath the spread blankets. One of the women, pregnant herself, leant over the child, her eyes frightened and troubled—and then all at once the baby gasped, gave a sneeze, and opening its mouth began to yell. The women sighed, relieved.

“Sarah—” the midwife said softly.

The pregnant woman looked up. They exchanged some words in low murmuring voices and then—as the midwife went to the fireplace and sat down to bathe the child from a basinful of warm red wine—the other slid her hands beneath the blankets and with firm gentle movements began to knead the mother’s abdomen. There was a look of strained anxiety on her face that amounted almost to horror, but it vanished swiftly as the woman on the bed slowly opened her eyes and looked at her.

Her face was drawn and haggard, with the strange new gauntness of prolonged suffering, and her eyes lay sunk in dark sockets. Only her light blonde hair, flung in a rumpled mass about her head, seemed still alive. As she spoke her voice, too, was thin and flat, scarcely above a whisper.

“Sarah—Sarah, is that my baby crying?”

Sarah did not stop working but nodded her head, forcing a quick bright smile. “Yes, Judith. That’s your baby—your daughter.” The baby’s angry-sounding squalls filled the room.

“My—daughter?” Even exhausted as she was, her disappointment was unmistakable. “A girl—” she said again, in a resentful tired little whisper. “But I wanted a boy. John would have wanted a boy.” Tears filled her eyes and ran from the corners, streaking across her temples; her head turned away, wearily, as if to escape the sound of the baby’s cries.

But she was too exhausted to care very much. A kind of dreamy relaxation was beginning to steal over her. It was something almost pleasant and as it took hold of her more and more insistently, dragging at her mind and body, she surrendered herself willingly, for it seemed to offer release from the agony of the past two days. She could feel the quick light beating of her heart. Now she was being sucked down into a whirlpool, then swirled up and up at an ever-increasing speed, and as she spun she seemed lifted out of herself and out of the room—swept along in time and space ...

Of course John won’t care if it’s a girl. He’ll love her just as much—and there will be boys later—boys, and more girls, too. For now the first baby had been born it would be easier next time. That was what her mother had often said, and her mother had had nine children.

She saw John’s face, the shock of surprise when she told him that he was a father, and then the sudden breaking of happiness and pride. His smile was broad and his white teeth glistened in his tanned face and his eyes looked down at her with adoration, just as they had looked the last time she had seen him. It was always his eyes she remembered best, for they were amber-coloured, like a glass of ale with the sun coming through it, and about the black centers were flecks of green and brown. They were strangely compelling eyes, as though all his being had come to focus in them.

Throughout her pregnancy she had hoped that this baby would have eyes like John’s, hoped with such passionate intensity she never doubted her wish would come true.

From the time she had been a very little girl Judith had known that one day she was to marry John Mainwaring, who would, when his father died, succeed to the earldom of Rosswood. Her own family was a very old one in England—their name had been de Marisco when they had first arrived with the Norman Conqueror, but during the centuries it had changed to Marsh. The Mainwarings, on the other hand, had sprung to their greatest power in the last century, sharing the spoils from the break-up of the Catholic Church. Their lands adjoined and there had been friendship between them for three generations—nothing could be more natural than that the eldest Mainwaring son should marry the eldest Marsh daughter.

John was eight years older than she and for many years he paid her scant attention, though he took it for granted that eventually they would marry; the betrothal papers had been signed while he was yet a child and Judith no more than a baby. All during the years that they were growing up she saw him frequently, for he came often to Rose Lawn to ride and shoot and fence with her four older brothers—but he was no more interested in her than in his own sisters and merely tolerated, with good-natured indifference, her awe-struck admiration. He went away to school—first to Oxford, then to the Inner Temple for a year or so, and finally off to Europe for his Tour. When he returned he found her a young lady, sixteen years old and beautiful, and he fell in love. Since Judith had always been in love with him and the families were so well agreed, there seemed no reason to wait. The wedding was planned for August: the August that war began.

Judith’s father, Lord William Marsh, immediately declared for the King, but the Earl of Rosswood—like many others—spent some weeks of indecision before joining the Parliamentarians. Judith had heard the two of them arguing, time and again, for the past year or more, and though they had often grown so angry that they began to shout and brandish their fists, at the end they had always agreed to drink a glass of wine and talk about something else. She never guessed that the quarrels might change her life.

The Earl of Rosswood had said a hundred times that he could stand Charles I’s absolutism, but not Laud’s church policy—while Lord Marsh was convinced that should the crucial moment come his friend would gather his wits and go with the King. When Rosswood did not he was shocked and furious, incredulous at first and then filled with bitterness and hate. Judith had not actually realized that England was at civil war until her mother coolly told her that she must think no more of John Mainwaring—the wedding would never take place.

Stunned, Judith nodded her head in agreement—but she did not really believe it. The war would be over in three months, her father said so, and when it was they would make up the quarrel again and all be friends. The war would be merely a brief unpleasant interval in their lives—it would change nothing of importance, undo no serious plans, destroy no old familiar customs. It would not really affect her or anyone she knew.

But when John came to tell her goodbye before he left for the army, Lord William rode out to meet him in a threatening rage and ordered him off the grounds. Judith cried for hours when she heard about it, for now he was gone away to war with never so much as a kiss between them.

A few days later Lord William and her four brothers went to join the King and with them went most of the able-bodied men on the estate and from the village. The war began to seem real to her now and she hated it, resented the intrusion into her life which had been so secure, so gracious and happy.

As Lord William had predicted, success ran with the Royalists. His Majesty’s nephew, gigantic, handsome Prince Rupert, won victory after victory, until almost all England but the southeast corner was in the King’s hands. But the rebels did not give up, and the months began to drag on.

Judith was busy, for there was a great deal to do now that the men were gone. She had no time to practice her dancing or singing, to embroider or to play the spinet. But no matter how much work she did she continued to think of John Mainwaring, wondering when he would come back to her, still planning for a future untouched by civil war. Her mother, who guessed easily enough at the reason for Judith’s thoughtful quietness, impatiently ordered her to put him out of her mind. She hinted that she and Lord William were planning another and more suitable marriage, to a man whose loyalty was unquestioned.

But Judith did not want or intend to forget John. She could no more have considered marrying another man than she could have accepted some strange new God thrust suddenly upon her.

When John had been gone five months he managed to send her a note, telling her that he was well and that he loved her. “We’ll be married, Judith, when the war’s over—no matter what our parents have to say.” And he added that as soon as he could he would come, somehow, to see her again.

It was mid-June before he was able to keep his promise. Then, making up some story to tell her mother, she rode out to meet him by the little stream which ran between the two properties. It was the first time in all the years they had known each other that they had been perfectly alone, free, and unwatched; and though Judith had felt apprehensive and nervously embarrassed—now she was off her horse and into his arms without hesitation or misgiving. Never before had she felt so sure of herself, so right and content.

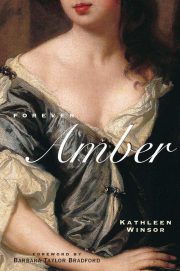

"Forever Amber" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Forever Amber". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Forever Amber" друзьям в соцсетях.