“Whatever your Grace knows,” said Amber, “I hope is true.”

“True? Of course it’s true! Let me tell you something, madame—I’ m the means by which her Ladyship’s complete and final downfall was accomplished.” He seemed smug now and satisfied with himself, as though he had performed an act of unselfish service to the nation.

Amber looked at him narrowly. “I don’t understand you, sir.”

“Then I’ll speak more plainly. I knew Old Rowley’s wish to be rid of her—but I knew also the kind of bargain she’d try to drive. It was very simple: I merely told him that the love-letters she’s been threatening to publish were burnt many years ago.”

“And he believed you?” Amber was now inclined to think that he had ruined Barbara, duped the King, and was maneuvering to take some advantage of her.

“He not only believed me—it’s the truth. I saw ’em burnt myself. In fact, I advised her to do it!” Suddenly he slapped his knee and laughed, but Amber continued to watch him carefully, not at all convinced. “She’s in a blazing fury. She says she’ll have my head for that one day. Well, she can have it if she can get it—but Old Rowley’s mighty well pleased with me just now—and I’ve got a mind to die with my head on. Let her scheme and plan how she may—her fangs have been drawn and she’s helpless. You’re looking somewhat cynical, madame. It can’t be you think I’m lying?”

“I can believe you told him about the letters—but I can’t believe he won’t take her back again; he always has before. Why should he give her that house and promise her a duchy if he had done with her? It runs through the galleries he even had to borrow money to buy Berkshire.”

“I’ll tell you why, madame. He did it because he’s softhearted. When he’s had all he wants of a woman he can never bring himself to throw her aside. Oh, no. He must always deal fairly with each of ‘em, recognize their brats whether they’re his or not, pay ’em off with great sums of money to keep ’em from being slighted by the malicious world. Well, madame—I should think this would be good news to you. It was never my opinion you and Barbara Palmer had overmuch fondness for each-other.”

“I hate her! But after all the years she’s been in power—I can scarce believe it—”

“She can scarce believe it herself. But she’ll get accustomed to it before long. I was tired of her vapourings—and so I took steps to be rid of her. She’ll hang on here at Whitehall, perhaps for years, but she’ll never count for anything again. For once Old Rowley is thoroughly tired of anyone, whether man or woman, he has no further use for ’em. It’s our best protection against the Chancellor. Now, madame, it’s occurred to me that this leaves a place wide open for some clever woman to step into—”

Amber returned his steady stare. No ally of Buckingham’s was much to be envied. The Duke engaged in politics for nothing but his own amusement. He had no principles and no serious purpose but followed only his temporary whims, rejecting friendship, honour, and morality. He was bound to no one and to nothing. But in spite of all that he had a great name, a fortune still one of the largest in England, and high popularity with the rich merchants, the Commons, and the people of London. Even more persuasive, he had a streak of vindictive malice which, though not always persistent, could do vast damage at one impulsive stroke. Amber had long ago made up her mind about him.

“And suppose someone does take her Ladyship’s place?” she inquired softly.

“Someone will, I’ll pass my word for that. Old Rowley’s been governed by a woman since he first took suck from his wet-nurse. And this time, madame, the woman might be you. There’s no one in England just now with so happy an opportunity. Those gentlemen who are keeping company with the Duchess of Richmond these days are but washing the blackamoor. She’ll never please his Majesty long—that empty-headed giggling baggage. I’ll venture my neck on it. Now, I’m an old dog at this, madame, and understand these matters very well—and I’ve come to offer my services in your behalf.”

“Your Grace does me too much honour. I’m sure it’s more than I deserve.”

The Duke was suddenly brisk again. “We’ll dispense with the bowing and nodding. As you know, madame, if I like I can help you—in your turn, you may be of some use to me. My cousin made the mistake of thinking that all her business was done for her in bed and that it made no difference how she carried herself otherwise. That was a serious error, as no doubt she understands by now—if she has wit enough to see it. But that’s all water under the bridge and need not concern us. I admit to you freely, madame, I’ve made a lifelong study of his Majesty’s character and flatter myself I know it as well as any man who wears a head. If you will be guided by me I think that we might go near to molding England in our own design.”

Amber had no design for molding England and no wish to invent one. Politics, national or international, did not concern her except in so far as they affected the course of her personal wants or ambitions. Her intrigues did not extend—intentionally, at least, beyond the people she knew and the events she could observe. She was inclined to agree with Charles that his Grace had windmills in the head—but if it pleased the Duke to imagine himself engaged upon great projects she saw no reason to argue with him about it.

“Nothing could please me more, your Grace, than to be your friend and share your interests. Believe me for that—” She lifted her glass to him, and they drank together.

CHAPTER FIFTY–SEVEN

FRANCES STEWART WAS not long satisfied with her life in the country. She had always lived where there were many people, balls and supper-parties, hunting and plays, gossip and laughter and a continual rush of petty excitements. The country was quiet, days passed with monotonous similarity, and compared with the Palace her great house seemed lonely and deserted. There were no gallants to amuse her, flatter her, run to pick up a fan or help her down from horseback.

Her husband spent much of his time in the field and when he was home he was too often drunk. The steward managed the house—which she had never been trained to do anyway—and the idle hours bored her desperately, for no one had ever encouraged her to learn to be happy alone. She did not like being married, either, but of course she had not expected to like it.

She had married because it had seemed the only way that she could be an honest and respected woman—and that had been the wish of her life. No doubt the Duke really loved her and was grateful she had married him, but he seemed to her dull and uncouth compared with the well-bred gentlemen of Whitehall who had a thousand amusing tricks to make a lady laugh.

And love-making revolted her. She dreaded each night as it began to grow dark, and invented many small illnesses to keep him away. She had a horror of pregnancy which sometimes made her actually sick, and more than once she experienced all the symptoms without the actuality.

Constantly she thought of the Town and Court and the fine life she had had there—which she had not valued at a great price then but which now seemed to her the most pleasant and desirable existence on earth. She spent endless hours dreaming of the balls she had attended, the clothes she had worn, the men who had gathered around her wherever she went to fawn upon and compliment her; she lived over again and again each small remembered episode, feeding her loneliness on them.

But more than anything else, she thought of King Charles. She considered now that he was the handsomest and most fascinating man she had ever known, and she had found to her dismay that she was in love with him. She wondered why she had not been wise enough to know it sooner. How different her life might have been! For now that she had her respectability it seemed much less important than her mother had assured her it was. What else could a woman need—if she had the King’s protection?

She longed to return to London; but what if he was not ready to forgive her? What if he had forgotten he had ever loved her at all? She had heard of his most recent mistresses: the Countess of Northumberland, the Countess of Danforth, Mary Knight, Moll Davis, Nell Gwynne. Perhaps he had lost all interest in her by now. Frances remembered well enough that once people were out of his sight—no matter how well he might like them—he promptly forgot their existence.

She tried to take an interest in painting or in playing her guitar or in working a tapestry. But those things did not seem entertaining to her, done alone. She was thoroughly, wretchedly bored.

Finally she coaxed the Duke to return to London, and at first her hopes ran exuberantly high. Everyone came to her supper-parties and balls. She was as much courted and sought-out as she had been after her first triumphant appearance at Whitehall. She knew perfectly well that everyone now expected the King would soon relent and make her his mistress, and for the first time she was almost ready to accept that position with its advantages and hazards. But Charles, apparently, did not even know that she was in town.

That went on for four months.

At first Frances was surprised, then she became angry, and finally hurt and frightened. What if he intended never to forgive her? The mere thought terrified her, for she knew the Court too well not to understand that once they were convinced he had lost interest they would flock away, like daws leaving a plague-stricken city. With horror she faced the prospect of being forced to return to her life of idle seclusion in the country—the years seemed to spin out in an endless dreary prospect before her.

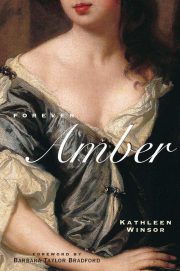

"Forever Amber" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Forever Amber". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Forever Amber" друзьям в соцсетях.