At the back of the church the doors are closed noisily and the organ falls silent. I can hear the sound of the bells outside dying away, thinning out raggedly to a whisper. Through a small door at the front of the church a group of men walk inside in a row, one behind the other. Immediately the shuffling and coughing is hushed, which means that these men must be very important people. With a jolt of pride I see that Hait is with them. I watch him sit down in the pew beside the pulpit, next to the schoolmaster and the man who brought me to Laaxum on the bicycle.

‘Who are those men? What are they going to do?’

‘Elders,’ whispers Meint. ‘They’ll be collecting money in a minute.’

The shirt Meint is wearing is frayed at the edges and has been patched with pale blue material. He looks ill at ease in the buttoned-up shirt: instead of just his head he turns his whole body towards me as if his back hurts.

The minister has a young, unwrinkled face above a chalk-white pair of starched bands. He wears thin, gold-rimmed spectacles which he pushes up his nose with a finger. He has come in without my noticing, and stands there in his full, black garb like an apparition. Without looking at anyone he walks quickly in a half-circle around to the short flight of steps to the pulpit, places a small book next to the large open Bible and looks out over the congregation attentively.

I wonder if he has seen me, if he realises that I am new. Perhaps ministers know everything. I make myself small and cast my eyes down. Just don’t let him call me out of the pew.

‘Dear people, let us pray…’ All this praying has become torture for me: we pray before and after every meal, at school and before we go to bed. I entreat food and health for those at home, I implore for a letter from them, I invoke their deliverance from death. The most repellent and shocking images pass before my shut eyes, visions I conjure up and no longer know how to banish.

The minister reads out passages from the Bible and after that he holds forth, endlessly and incomprehensibly. Interminable, dreary boredom.

I look at the tall elongated windows through which I can see branches and a piece of the sky and a swallow that swoops twittering in through one window and out of the other. Do the others notice as well, do they see it, or am I the only one watching its nimble flight? Unerringly the little bird darts out through the narrow gap to cut through the blue sky, and I wait patiently to see through which window it will return.

‘Woe unto them! for they have gone in the way of Cain, and ran greedily after the error of Balaam for reward, and perished in the gainsaying of Core. These are spots in your feasts of charity, when they feast with you, feeding themselves without fear: clouds they are without water, carried about of winds; trees whose fruit withereth, without fruit, twice dead, plucked up by the roots…’

Streams of disjointed words without meaning, pouring out unstoppably, phrases that baffle me and turns of speech that make me first giddy and then sleepy. How much longer will he go on, surely he can’t keep talking for ever? Clouds move by in the blue sky and the leaves on the branches are beginning to rustle. It won’t be long before it rains.

If I stare at the minister long enough perhaps that will make him stop, perhaps he’ll realise then that enough is enough. I glance at the faces all around me, weather-beaten, tired, rapt. They listen with a kindly, childlike attention that looks like wonder. Do they really understand it all, and is that because I hey have heard these words all their life?

They sing: dour, dragging melodies played through first by the organ, then fumbled through routinely by the congregation. Meint holds the text in the little book up to me and I try to sing along looking as natural as possible. Sometimes my voice goes suddenly in the wrong direction, an unexpectedly loud sound, an incongruous and blatant discord. I grope for the right tune, floundering helplessly among the notes, and in the end do nothing but move my lips industriously. Perhaps the minister will not hear my mistakes, though the master may well have told him about them already. Moses, Joseph, David…

With the next bit of the sermon I am suddenly back home in Amsterdam, looking stealthily at a book with an exciting illustration: a woman without clothes is sitting down and bending forward, her white flesh making fat, soft, curves. Behind her, two old men are standing with surly, furtive expressions. One holds his chin reflectively, the other places a surreptitious hand on the woman’s bare belly. ‘Susanna and the Two Elders’ it said underneath and I hear these very words in the sermon.

The men at the front of the church are called elders. How can that be? Could those men, and could Hait…? I can’t imagine that, him doing it to Mem, those bony hands on a round, bare belly. Why do they talk about that sort of thing in church?

At the end of the sermon the elders walk one behind the other down the central aisle. They stick out black pointed velvet bags on long handles and people put their hands into them. The men shake the little bags and the jingling of money rings through the church.

I put in the cents Mem gave us when we left home. At first I had thought I would keep the money, it would prove useful for our escape, but then God might have seen it and punished me. When my coins jingle I look up: You see, God, my money is inside.

The sticks move on through the church like scythes, making greedy, poking movements, fingers pointing at each successive victim. An ill-omened, avaricious dance of death.

I squeeze out of the church and breathe in the smell of the meadows.

When we are walking back home, back to Mem, back to dinner, my life seems happy, light and carefree. I see everything through brand new, clean-washed eyes, as if I were looking down from a cloud and watching everyone, myself included, walking down the road like small, contented insects.

When we leave the road and start to cross the meadows, I can already smell the food. Mem stands waiting for us by the door and as soon as we are inside she begins to move pans .Hid dishes about. On Sunday her cooking is always a little bit Special: there are gooseberries in a bowl, or cooked apples, bid sometimes warm buttermilk porridge with syrup.

If it is buttermilk porridge then my Sunday is very nearly spoiled, the smell alone makes me feel sick. And if, following persistent urging, I take a mouthful, all my good resolutions carried away from the sermon vanish together with that spoonful of sour-sweet, slimy sludge.

‘Go on, eat up,’ says Mem, ‘it’s good for you, it’ll make a man out of you.’

Heavy and full of food we go back to church in the afternoon. Most Sundays Mem comes along as well. It is the only day in the week she ever leaves Laaxum.

After the afternoon service, which seems even more incomprehensible than the one in the morning and spreads a sleepy boredom over us all, the children go on to Sunday school while the parents visit friends or promenade up and down the village street. Downcast, and with a bitter taste of helplessness in my throat, I sit in the gloomy, damp little building with the cast-iron windows. I look at the spot where I sat that first morning, at the cupboard with the folded clothes, the table where the driver sat. It is a classroom filled with the memory of the group of waiting children with troubled, grubby faces.

Weary, grumpy or resigned, we allow a fresh stream of religious learning to wash over us. All the while I keep thinking of Jan, of how he left this place without so much as a glance in my direction. Why did my father ever allow me to leave home, to end up with this lonely existence, stumbling about as I vainly try to find my feet? And how can I be sure that things won’t go on like this for evermore, that the war won’t continue for years and years?

I am filled with anger and resentment against my new home, against this life with its endless sanctimony concerning eternity, sin and redemption, trickling its way drop by drop, word by word, into my weary head. Dispirited and beleaguered I try not to let anything more filter through to me, try to cut myself off from the monotonous voice, the booming bellow, the echoing drone.

‘The panting hart, the chase eluded,

thirsts as ne’er before for joy…’

When Pieke sees us coming back home she runs staggering across the field, her little arms flailing the air helplessly. ‘Just look at that,’ says Jantsje, ‘she can’t wait.’ Rebellion and impotence grate inside me. Bells keep ringing in my head, my eye sockets feel hollow and empty. I no longer want to live. Why do I have to go on with it all? Drained, I cross the road and watch Pieke, that maimed bit of life who, shamelessly disregarding the day of rest, is making her way towards us with flailing arms, distracted with joy.

Chapter 7

The red cliff rises from the flat land like a strange growth. From Laaxum the path runs along in the lee of the sea dyke and then up the slope of the Cliff to the top. At the highest point you can look far across the countryside, you can see Laaxum and Scharl, where Jan lives. Much further towards I lie horizon, the steeple of Warns church sticks up, and to the lilt, where the dyke makes way for a mass of tiny roofs, masts and treetops, lies Stavoren. Everything seems small and still. The sea, which makes up the other half of the view, puts an abrupt end to the all but treeless stretches of pasture, the dyke creating a sharp divide between the green land and brownish-black water.

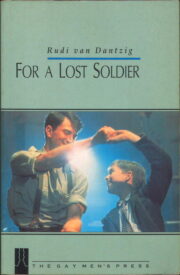

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.