A hush did not fall until the father said commandingly, ‘That will do for now.’ He had come in on black wool-stockinged feet, wearing an old, too-short pair of trousers on his skinny body. He surveyed me with a small lop-sided smile in the corners of his mouth.

‘So you’ve come from the city to see for yourself how we get on here, eh? Well, we can show them a thing or two in Amsterdam, eh, boys?’ He looked around the room. ‘We’ll soon make a man out of him.’

He put a hand on my shoulder and then sat down facing me. Preparing for a new cross-examination, I thrust myself back in my chair as far as I could. The man bent over forward and rubbed his feet, one after the other, an agonised expression on his face. The lame girl went to her father’s side with an exaggerated show of affection. She placed her hand on his knee and leant her head against the back of his chair, looking at me curiously as she did so. I could see she was putting this on for my benefit.

‘That’s your new comrade, Pieke, her father had said. ‘Go and show him round the house, so that he’ll know his way about.’

But the two of us kept our distance and didn’t move. I tried to avoid meeting the girl’s eyes and looked uncertainly at the father. I could sense he was a gentle man and that he was taking me for what I was, without any fuss. His gestures were made with deliberation, it looked at times as if he were caressing the air. He sat very quietly, and his look in my direction was friendly and reassuring.

While he’s there, I thought, things will be a bit easier.

The girls came in with the plates and the cutlery and pushed everything about on the table, making a great deal of noise. The father put his hand on my shoulder and showed to my place. ‘Between Popke and Meint. All the menfolk together.’ He looked round to see if everyone had sat down and said briefly, almost inaudibly, ‘Right.’

The scraping of chairs stopped. Stillness settled over the .mall room like a heavy blanket. The family sat with folded I lands, heads bowed. I looked at the big woman who gave the impression of watching me even with her eyes closed. She made a strange movement with her mouth, as if her teeth had slipped forward a little. I quickly shut my eyes and took up I he same posture as the others, peeping out of the corners of m v eyes to see when the prayer was over. Suddenly there was a chorus of mumbled voices, ‘Bless, oh Lord, this food and drink. Amen.’

‘Don’t your people say grace before meals?’ the woman asked. I searched for an explanation that would ring true but I her father answered for me.

‘People in the city are used to something else, eh boy? Aren’t they?’

He gave a brief laugh as though he had seen through me.

Potatoes with meat. I can’t remember how long it has been nice we last ate meat in Amsterdam. And here you can have i; much as you like, all you need to do is hold up your plate.

The meal goes by silently and quickly. Things I was never allowed to do at home seem quite all right here: they put their elbows on the table and bend their heads low over their plates. They watch me eat. I have difficulty getting the food down and have to swallow hard. I try to put down my fork without being noticed, but I can feel the woman’s eyes upon me. The smell of the food gives me a queasy feeling in my stomach. Now and then someone says a few words, then they go on eating in silence. I listen to the sound of the forks and the swallowing and chewing.

My stomach gives a spasm and before I can hold it back I belch violently. I feel myself turning red with embarrassment, but no one seems to pay any attention to my lapse. Only the woman halts her fork halfway up to her mouth and stares at me.

When everyone has finished eating, the father says ‘Diet,’ in the same brief tone. The girl in the tight dress gets up and takes a book from the small sideboard.

‘Moses commanded us a law, even the inheritance of the congregation of Jacob.’

The book lies open on her lap and she reads in a monotonous drone. I try to understand what she is saying. Every so often she reads a few words twice over, the second time altering the pitch of her voice and allowing the sound to die away. That means it’s the end of a sentence.

‘And he was king in Jeshurun,

when the heads of the people

and the tribes of Israel were gathered together’

Her voice is high-pitched.

‘Were gathered together.’

Her voice falls and tails off.

During the recital, everyone seems to be dropping off into an after-dinner nap. The girl claps the Bible shut and puts it back on the sideboard matter-of-factly. The mother looks pleased and satisfied, even with me. When they all fold their hands again, I know that the meal is over. Suddenly I am hungry. Will we be getting a cooked meal tonight as well?

A shiny strip of sticky paper in twisted coils hangs over the table, strewn with little black lumps of flies. One of them is still buzzing, so violently that I can feel the vibrations all along my spine. Dear God, please let me go back home soon. Help them in Amsterdam and protect them. I shall do whatever You say. Do I have to pray for the fly as well?

The chairs are pushed back from the table and everybody gets up. What next? Something new, or back to my chair? Meint and the disabled girl leave the room. I feel a push from the father’s hand. ‘Go have a look outside, why don’t you.’

When I step out of the door the wind hits me with great force, taking my breath away and nearly blowing me over. I lean into the billowing wind, gasping for breath, and am

driven two steps back.

The two children disappear around the corner and sit down on a small bench by the side of the house where the wind is less fierce. I trail after them awkwardly and try to think of something to say or to ask.

‘Behind that dyke,’ says the boy, ‘is the harbour. That’s where our ship is.’

He points. The girl makes room on the bench. Carefully I push in next to her. The long grass on the dyke is forming fanciful shapes in the wind, rippling like swirling water.

‘I’m Meint,’ says the boy and holds out his hand. ‘We are brothers now.’

Where the road runs up along the dyke, I can see several masts between the roof of a farmhouse and the top of a tree, bobbing to and fro in an ungainly dance. ‘Are you allowed to go sailing in the boat sometimes?’ I ask the question carefully, but the girl explodes into derisive laughter as if I had said something stupid.

Meint gives her a prod so that she tips over onto the grass. ‘She had polio, and now she’s got a bad leg. She isn’t used to city talk,’ he adds apologetically. The girl hobbles restlessly to and fro in front of us as if trying to wear herself out. A little bird in a cage.

Our house is the last in the small village. It stands apart from the other houses that lie at the foot of the dyke. Quite a long way past the village I can see how the dyke slopes gently upwards in a tapering hill, with cows grazing there, small as toys. ‘That’s the Cliff,’ says Meint.

The sound of clogs can be heard from behind the house. The father and the boy called Popke walk outside. ‘Meint, will you bring the bucket along for us?’ Meint jumps up and races to the shed. He swings the bucket through the air, then runs and catches up with the two men. The girl lets herself slide off the bench and limps wailing after them through the meadow. She comes to a halt at the gate which the boy has climbed over and kicks angrily at the bars. Then she lets herself fall down on the grass.

I see the woman in her dark clothes rushing across the meadow. Her size and the speed with which she is moving have something intimidating about them. She drags the girl to her feet and propels her back to the house. By the shed she gives the sobbing child a slap round the ears and shakes her furiously. ‘You scamp, always the same carry-on. Things can’t be the way you want them all the time.’ She thrusts the shrieking girl in my direction. ‘Whatever must this boy be thinking, he’s never heard the likes of it.’

The girl scrambles back up on the bench next to me. I notice she has two big new front teeth. On either side there are gaps and the rest of her teeth are brown and uncared for. She kicks against the bench and the iron brace around her thin little leg makes a clanking sound with each kick. With every clank I shut my eyes. What would my father be doing now in Amsterdam?

I feel misery closing in on all sides, in the emptiness, in the outbursts, in the aimless sitting and waiting: it rushes through the pastures, it howls and screeches, it disappears behind the dyke swinging a bucket. Suddenly I am dying to find out where the woman has put my suitcase, I long to open it and to hold the familiar things from home in my hands. I must stow all of it safely away so that no one can find it. But I don’t know whether I’m allowed back in the house. Should I go and ask?

The oldest girl is busy cleaning the pans in the shed. The mother is nowhere to be seen. I walk back to the gate. Is every day going to be like this one? I can smell the sickly sweet smell of manure blowing on the wind. Everything around me is green and remote. When the sun breaks through the clouds for a moment, I suddenly see lighter patches and the brown of the roofs, the wall of our house lit up bright yellow. The girl is sitting sulking on the bench, her head hunched between her shoulders, and she is making angry kicking movements with her leg in the air.

Towards evening the men come back, their hands reeking of fish and petrol. With a triumphant roar Meint puts the bucket down on the little stone path. Dozens of gleaming, grey slimy eels are writhing together in apparent panic. They have pointed heads and staring, cold little snakes’ eyes. I look spellbound at the squirming tangled ball.

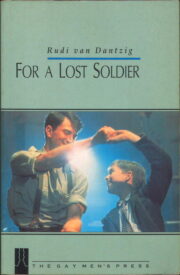

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.