‘Psst, come and look at this.’

We go into a w.c. cubicle with a sharp, penetrating stench. Jan points up to a corner of the wall where a small sign has been scratched, a sort of circle with a line through it and a dot in the middle.

‘Cunt,’ says Jan triumphantly. He laughs and slams the little door shut. I hear him racing up the iron stairs.

Our mothers have gone inside, because it’s too hot on deck, they say. We have a drink of milk from the bottle Mem gave us and eat a clammy sandwich. ‘The bread in Amsterdam must be less coarse than this by now,’ says Jan’s mother arid I wonder how this can be with the war hardly over.

I feel myself getting furious: they’d better not start running Friesland down all of a sudden.

Jan leans against his mother and goes to sleep; my mother has shut her eyes as well. There is a leaden silence and scarcely a breath of wind comes through the little open windows. For a while I listen to the muffled thudding of the engine, then I get up and walk quietly around the deck until I find the windows where we heard the voices. There is the sound of soft music and of people talking so low that I can hardly make anything out, even when I stand right next to the porthole. As soon as anyone comes by, I go quickly and lean over the railing, pretending to study the sprawling waves, but a moment later I am back trying to look into the little half-open window to catch a glimpse of what is going on inside, waiting for the sound of a familiar voice.

Suddenly someone is looking me straight in the face, then with a furious tug the small curtain is drawn.

Enormous numbers of close-packed houses, roofs, cranes, the commanding dome of the Central Station and everywhere people and bicycles, a mysterious, bustling, gloomy world: that’s how Amsterdam looks to us as we watch it slip by from the deck. Even Jan is silent and subdued. He leans on the railing, looking tired, and has nothing to say.

Army cars are parked alongside the station, not just a few but scores of them. I pretend to be looking elsewhere, at the milling crowd on the waterside, at the crowded quay, and I try hard to make conversation with my mother. But my mind is elsewhere.

‘Come on, pick up your things,’ she says, ‘it’s time we went down.’

We stand beside our bicycles anxiously and nervously, ready to disembark as quickly as possible.

‘Stay by me,’ says my mother, ‘hang on tight to the luggage carrier, or else I’ll lose you in the crowd.’

A lot of people are standing on the landing stage, some craning upwards as if looking for somebody, but most seem to be hanging about aimlessly. We go down a gangplank much broader than the one in Friesland, hemmed in by the other people from the boat. Dusk is falling and I feel cold.

‘Isn’t Daddy coming?’

‘Of course not, he doesn’t know when to expect us, this way we’ll be giving him a surprise. He’ll be at home as usual, looking after Bobbie.’

Bobbie! When I get home there will be a baby, a little brother waiting for me in this dark, mysterious city.

We tie on the luggage a bit tighter as Jan jumps up and down impatiently, dying to be off. As we start bicycling I can see that the soldiers, wearing rucksacks, are just coming off the ship. I wrench around so suddenly to look at them that my mother nearly falls to the pavement. Then, like an oppressive shadow, the back of the station engulfs us.

The evening sun shines over the Rokin where hundreds of people are milling about. Everywhere there are flags, placards, decorated lampposts and triumphal orange arches, an overwhelming riot of colour and sound.

And everywhere I can see uniforms and army cars, driving around or parked in the street; a truck full of singing soldiers brushes right past us. I shall find him again, of course he is here. I wonder if he is living in a house or if they have put up tents somewhere, near us perhaps, on the field by the Ring Dyke.

His bare legs will fold around me again, his fingers close teasingly about my thin neck. Keep bicycling, Mum, come on, quickly, I want to get home, I want to make plans!

We swing off towards Spuistraat and at the turning I look at Jan, waving both arms enthusiastically at him. ‘Don’t be silly, hang on tight or we’ll have an accident.’ I cling to the yellow dress again and feel the rotating hip joints.

The Dam is like an ant-heap, impossible to get through, and the street alongside the Royal Palace has been blocked off. We have to dismount and make our way through the crowd on foot, my mother ringing our bicycle bell for people to make way. I peer over the barrier into Paleisstraat; it looks eerily empty and deserted, as if some disaster has struck it. That’s where the lorry had stood, parked right next to the Royal Palace. The sparrows twittering in the sun seem to be the only thing I can still remember clearly.

The Rozengracht, and we get back onto our bicycle.

‘Mummy, a tram! Are the trams running again?’

We bump over the uneven road and I become steadily more excited as I recognise more places and as everything starts to look familiar and to tie in with my old life. On Admiraal de Ruyterweg workmen are busy laying sleepers under the rails, the large piles of wood surrounded by groups of curious neighbourhood children.

‘See how hard they’re working? They go on right through the night. Everything has to be repaired.’

I say nothing. We’ll be home in just a moment. How dark and bare it looks here, all the trees gone. Across the big stretch of sand I can see our housing block, sunny and out in the open, and children digging holes and chasing one another through the loose sand, shouting and laughing.

My heart beats violently and my joy evaporates. The boys, school, break: ‘Wait till we catch you alone, you’ll get what’s coming to you after school!’ Fleeing back home, back to the safety of our doorway.

Our street. Open windows and balcony doors, and yet more tricolours, stretched-out lines with little fluttering flags, strange white stripes chalked down the street like a sportsfield.

And, in the middle of the street, the patch of grass. The remaining rose bushes are in bloom.

I feel dizzy and dejected. What I would like best would be to disappear and arrive back home unseen. As it is, a lot of people seem to be standing at their windows especially to have a look, and when we dismount outside our door children come running up to the bicycle.

I shake Jan’s mother’s hand to say goodbye. Jan has already run across the road and is shouting up to the balcony where his father and little brother are standing. I walk quickly across the pavement past the children and bolt inside the building. I am so confused that I haven’t taken in who anybody is.

My mother puts the bicycle in the lock-up and I stand in the doorway and peer inside, listening to her rummaging about in the dark and untying the panniers.

‘Will you carry this?’ As we go up the stairs I can hear voices, and without having to look I know that somebody is hanging over the banister and looking down the stair-well.

The neighbours and my father are standing on the second-floor landing. He is beaming all over – What a funny face, I think – flings his arms around me and pulls me close. Dazed and numb I allow it to happen, and then we go on blankly to shake hand after hand.

‘Leave him be,’ says my mother in a whisper, ‘he’s tired, we’ve been travelling all day.’ And then, louder, ‘Hey, Jeroen, we’re going to go up now and then you can get in your own bed, won’t that be nice?’

‘Doesn’t he look terrific?’ she asks my father when we are upstairs.

They are standing side by side in the passage and look at me with the eyes of children who have wound up a toy animal that then begins to move as if by magic. ‘When you hear him talk you’ll hardly understand him. He’s turned into a real country boy.’

Inside, I see immediately that the furniture has been moved: this is not the room I kept thinking about in Fries-land, this one is different and strange. Against the wall, where the sideboard ought to be, there is a baby’s highchair. A small, solid person with fair, curly hair is sitting in it giving me a frank inspection with expressionless eyes as if to say, ‘What on earth are you doing here?’

‘Give him a kiss, go on.’ My mother pushes me gently towards him, but he begins to scream and leans far out towards my mother. Is she my mother any more? She lifts him out of the chair and tries to turn him towards me.

‘Yes, sweetheart, Mummy’s back, don’t cry. Just look who’s come. That’s your big brother, he’s back with us for good now. Say "Hello, Jeroen".’

She tries to drown the deafening screams. ‘He can say a few words already: dada. Go on, say dada. He can say mama as well and we’ve tried to get him to say Jeroen, sometimes he says toon.’

But the fair-haired little boy doesn’t say toon, it takes quite some time before the house is quiet again and I am depressed and aggrieved to see how often they keep on going to the cot to try and calm him down.

‘The shower isn’t working yet,’ says my mother. ‘Shall I give you a wash in the kitchen?’

How can I tell her that I’d rather do that on my own. ‘In Friesland,’ I say, ‘we always had to wash ourselves.’

She puts out a tub in the kitchen and mixes a kettle of boiling water with cold water from the tap.

‘You can go now,’ I say, and shut the kitchen door.

I remember in amazement how, before I left, she would soap me down every Saturday night while I stood shivering beside the little tub.

‘Here are some clean underclothes, I shan’t look, no need to get alarmed,’ she says teasingly and her arm places some clothes on the edge of the kitchen dresser. I allow her back in when I have put on my underpants.

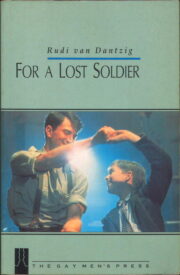

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.