If we stopped, I could look around, even explore a little along the path. The road seems familiar, those overhanging trees and the low bushes on the verge.

‘How about a short rest, Mum? I’m as stiff as a board.’ It’s no more than the truth, because I have to sit on the luggage carrier with my legs spread wide across the two full panniers and the insides of my thighs feel as if sandpaper had been run over them. But my mother pedals on obstinately until we catch sight of the other two by a side-road.

We sit down on the verge and Jan’s mother unwraps a packet of sandwiches. ‘It all seems to be forgotten again,’ I hear my mother say in a half-whisper, ‘how quickly things change: one moment they’re crying and the next they’re having the time of their lives.’

I chew my sandwich and look down the side-road for a roof between the trees with a small dormer-window. When I think of that room I can still smell the wood and the blankets on the mattress.

Jan, who is already starring on his third sandwich, sits leaning against a tree on top of the verge. He flicks off the ants running over his legs with his fingers, aiming them towards me. ‘Nice, a trip like this, isn’t it? You get to see quite a bit.’

He doesn’t realise that I have been here before and much further too, with an American soldier, in an army car. From where I am sitting I can look up his trouser leg, up his smooth, slim frog’s thigh. But I am unmoved and can hardly believe that once upon a time – long, long ago – I used to yearn so desperately for that body, that I would dream about it, torturing myself with the mere thought of it.

I walk as nonchalantly as possible to the other side of the road and peer between the trees to see whether there is a clearing or an old railway track inside that wall of green. The hairy legs tighten around my hips and the jaw rasps painfully across my neck and cheek while I listen to the breathless voice: ‘Hold it, yes, go on, move. Yes.’

The bicycles have been lugged up from the verge with much groaning and sighing and they are all looking at me

impatiently. Jan’s mother rings her bell. ‘If you don’t hurry up you’ll have to walk to Lemmer!’

Awkwardly, I manoeuvre myself, hopping and wide-legged, onto the luggage carrier and aim a furious kick at the bulging panniers.

‘Try and put up with it a bit longer. Just another hour, I think, and then we’ll be in Lemmer.’

She is pedalling again, the chain creaking and the wheels making heavy weather of the forest path. I am tired, I want to rest my head against her back. Any moment now I’ll fall off the bicycle. There is rye-bread stuck in my mouth which has a sour taste. I run my tongue over my teeth and chew on a left-over morsel.

If only I can remember Walt’s taste, his breath and his spittle in my mouth. But how do you do that, how do you remember a taste, a smell?

Chapter 13

…Two men in blue overalls are standing by the boat, one carrying a rifle and looking ready to go into action any moment.

A small group of people has gathered on the quay, but to join them we must go past the two men.

‘Come on,’ says my mother, ‘nothing to be afraid of.’

I look back for Jan who is still standing with his mother by the small office where we paid for our boat tickets.

‘They’re coming. If we hurry we’ll be able to find a good spot on the boat.’

I walk with her up to the men, who ask to see her identity card, open up the panniers on the bicycle and search them thoroughly and suspiciously.

‘What on earth are you after, I thought the war was over?’ She says it curtly and yet her voice sounds cheerful. When the panniers are closed again, they start joking with my mother and I hear one of them call her ‘sweetheart’. I feel excited and almost flattered because they are being so nice to her, but at the same time they make me nervous and their easy laughter infuriates me.

‘Is the boy with you?’ they ask. ‘Is he going on the boat as well?’

‘He’s my son. He’s been in Friesland for a year and now we’re going back to Amsterdam. I’m fetching him home.’

The conversation comes to a sudden halt. Someone is bringing our bicycle up the narrow gangplank and we follow behind carefully. I can see the black water below and hear it making gurgling noises between the ship and the quay.

The ship looks enormous to me, bright and white and full of little stairs, doors and corridors. The wooden floors are wet, the puddles giving off a soft salty smell, reminding me of holidays and of Walt’s tent, of lashings of sweet-scented security.

‘Come along,’ says my mother, ‘let’s go and sit up on the deck, it’s lovely weather.’

We clamber up an iron stairway and I run to the rail and look down. The little town is quiet, there are just a few small houses around the harbour. I can see a baker’s shop, some fishing boats, a large pile of crates and the two men leaning against a fence and concentrating on smoking a cigarette.

‘How quiet it is,’ says my mother,’ I think there’s hardly anybody else on board. Can you see Jan and his mother?’

As I bend over further I hear Jan’s voice and see him running up the stairway.

‘Wow, what a great place.’

We race along the railing and go down another stairway, making for the front of the ship to watch the crates being loaded on board.

‘See that fellow? What a he-man,’ Jan says admiringly. But, secretly, I compare the man’s arms with the ones that I know, and look away unimpressed.

Our mothers are sitting silently on a bench in a sunny corner of the deck, suddenly looking tired and anxious. My mother has laid her head on her arms, looking across the water. Jan’s mother lies slumped over her bag with her eyes shut.

‘Are you tired, Mum?’

‘Just leave us be for a moment, darling. We’ve been bicycling for three hours, with you on the back, and we’re not used to it.’

I sit on the floor next to the bench and run my hand over the silky, uneven surface of the planks. The sun is hot and dazzles me. I look at the pannier and wonder what other food might be in it. Then the boat begins to judder, the planks shake softly under my hands and the trembling spreads right through my body. After a slight lurch I see that the quay has moved, that the houses are slipping away from us. I jump up and run over to Jan who is calling to me and hanging over the railings gesticulating wildly. Then there is a deafening noise, a shattering, almost unbearable hurricane in my ears that nearly scares me to death: the ship’s funnel emits a dark cloud of smoke like black vomit being blasted up into the sky.

My mother has clapped her hands to her ears, her face looking pale and miserable, and suddenly I realise that this is farewell to Friesland. I run back to the railing and stare at the harbour which already seems an amazing distance away from the boat.

My mother puts her arm around my shoulder. ‘Here we go,’ she exclaims and I have to listen very hard to hear what she is saying. ‘Take one more look. But next year we’ll go and visit them, that’s allowed again now.’ She sighs and then gives the receding little town an impulsive wave. ‘Bye Fries-land!’ She pulls me towards her and suddenly everything feels pleasant and carefree, as if nothing had happened. ‘That adventure is behind you now.’ Her hand touches my hair lightly, and I feel an irrepressible longing for the hand that slid down my back fingering me roughly and yet carefully and attentively. Suddenly I feel sick.

‘Are we going to have anything to eat? My stomach hurts.’

‘In a moment. We’ve only just started. Go and find Jan but don’t stay away too long.’

Listlessly I walk through the ship. The flag flaps above the bubbling water, making the same sound as a big fish flung by Hait onto the deck where it would beat on the planks, thrashing about, contorted with desperation.

The ship’s propeller churns up clouds of sand and air in the water and rolls them up to the surface, creating an eddying grey maelstrom, binding us to the mainland like a living, twisting cord.

The small town and the coastline have become a blur, an unknown domain I have never visited and at which I now stare with a stranger’s eyes. The sea is covered with scales of glittering and sparkling light that hurt my eyes. We have been cast into the void, adrift in a shoreless sea, and I would not be in the least surprised if Amsterdam never appeared, if our passage turns out to be a journey without end. Amsterdam, what is that to me now, what am I going there for?

Jan has joined me; he spits overboard and tries to follow the course of the blobs until they touch the water.

In the distance ships lean in the wind and I strain to make out the letters on their brown sails. Imagine if Hait suddenly drew up alongside to give me a surprise and I saw those familiar faces close-to again: Hait, Popke, Meint. Aren’t they coming nearer, isn’t one of them getting a little bit bigger?

The water glitters and the wind blows tears from my eyes. The little boats have hardly moved. When Jan calls to me, I quickly turn my head away in case he thinks I am crying.

‘There are soldiers on board,’ he says a little while later. ‘They’re keeping to themselves, they’re probably not allowed to mix with us.’

I almost force him to take me then and there to where he has made this discovery, and a moment later, peering furtively through some little round windows, I see the green uniforms and hear the familiar sound of voices speaking an incomprehensible language.

We clatter down a stairway. How can we find where they are, where is the way in? People are sitting about who look at us silently, bags and parcels beside them. They seem tired and worn out.

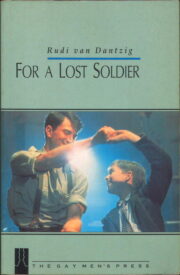

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.