Now I ought to put my arms around her neck, hold her tight and never let go again, tell her everything that happened while she listens patiently and finds the answer to all my problems. But again I don’t move and just stand there sullenly between the adults.

‘What do you say, young ’un, isn’t that something now? They must have gone at a fair lick to get here so quickly, musn’t they?’ Hait bends down and shakes my shoulders gently as if waking me from a deep sleep. ‘Don’t just stand there. Say something to your mother. Why don’t you show her round the house?’

I nod and say nothing. The words won’t come and my throat refuses to move. I lift my head to see if my mother is looking at me and discover that Jan’s mother is standing next to her with an arm around her. What is she doing with her hand over her eyes? Is she crying?

Then we all move into the house, somehow.

‘Why don’t you say hello to Mevrouw Hogervorst?’ My mother’s voice sounds worried, she whispers the words almost inaudibly into my ear. My feet are wet and cold from the grass and I put one on top of the other to warm them. Jantsje and Meint are standing huddled together in the semi-darkness of the room. I can hear their suppressed laughter and see that Meint is trying to draw my attention by waving his hands about urgently.

‘Scharl is a bit further back, you passed it on the way here.’ Hait is standing by the window and points into the dusk for the benefit of Jan’s mother. ‘In the daytime you can see it clearly, it isn’t far.’

Of course, they’ve come for Jan as well. Will they go back again after that, will everything be as before, this family, this little house, my loneliness? For a split second I fervently hope so.

‘I’ll walk with the lady down to the harbour to find Popke, then he can show her the way to Scharl. And I’ll bring your bicycle over the fence at the same time.’

My mother sits at the table, her eyes radiating light. As she looks around the room, her gaze always ends up on me so that I begin to feel ill at ease. It is strange to see her here, small and slender, a little bird unflustered by her sombre surroundings. She doesn’t belong here, I think, she makes the room look strange. The yellow dress, her townish ways of talking, the little shoes that she had kept on inside the house.

‘How small it is in here for so many people,’ she says, ‘it must be terribly hard for you with so large a family. Jeroen did tell us in one of his letters, but I never imagined it would be this small…’

Stop, I think, for goodness’ sake stop.

She strokes my cheek and I draw back shyly. ‘It was awfully good of you to be willing to take in one more.’

‘My goodness me,’ Mem folds her sturdy round arms, ‘it’s no more than our duty. God arranged it that way.’ She pours tea into the best cups with careful, almost respectful movements. ‘It’s nothing to feel grand about and for us one more doesn’t make that much difference.’

I hear a mixture of modesty and pride in her voice and her eyes are filled with the gentleness that always disconcerts me.

‘Jeroen has been a good boy. He’s never given us the least trouble. He was like one of our own.’

My mother pulls me towards her and takes me onto her lap. ‘Darling,’ she laughs brightly, ‘you come and sit with me. You’re a little bit more used to me again now, aren’t you?’

I strain away from her slightly.

The children are sitting around the table, unusually still and obedient, staring at the lady from the town without uttering a sound. I feel the gulf, plainly and painfully, and am ashamed.

‘Has he always been as quiet as that here?’ my mother asks softly and anxiously, as if I shouldn’t be listening. ‘Was he homesick a lot? You know, he always was a bit different, always a dreamer. He could sit in a corner playing for hours, not a bit like a child. Hey, Jeroen?’

Suddenly I fling my arms violently round her and cling to her tightly.

Walt, why aren’t you here? Why did you go away like that?

From her movements I can tell that she has begun to sob uncontrollably, although sometimes it almost sounds as if she were laughing wildly. I look at her in astonishment.

‘Yes, we’ll be going back home pretty soon now,’ she says. ‘Back to your Daddy and your little brother. Don’t cry.’

I am not crying.

Won’t Mem find it odd to see me sitting on somebody else’s lap, since I still belong a little bit to her too?

‘Are you glad that we’ll be going back home soon?’ asks my mother.

‘But not straight away,’ I say quickly and almost imploringly. It suddenly hits me that if we leave here, Walt will never be able to find me again; I will have vanished without trace.

In the cupboard-bed Meint whispers to me. ‘How pretty your mother looks, she could be your sister.’

I hear subdued voices from behind the cupboard-bed doors, and time and again they speak my name.

‘Perhaps I’ll be staying on here all the same,’ I say hopefully.

‘I’m sure she’s not taking me back with her.’ I no longer know what I really want. Leaving seems unthinkable and yet I don’t want to stay here either.

‘Ah, well,’ says Meint with a laugh and gives me a dig under the blankets. ‘In a month’s time you’ll have forgotten all about us.’

I hear footsteps and then the little doors open a chink. ‘Keep quiet and go to sleep,’ says Hait, ‘dream about being back home.’

When I am about to say my prayers I realise with surprise that I won’t need to pray for my parents any longer. The only one left will be Walt.

God, please keep him safe. Don’t let him be wanted for the war and please let him come back. I’ll always go to church, even in Amsterdam. If he just comes back.

He unbuttons my clothes and puts his hand inside my shirt, sliding it down between my shoulder blades. I shiver and stiffen.

Not until next morning does it really sink in that my mother is here, and then the day seems unimaginably bright and carefree. I scramble up the attic stairs to wake her up, but she is already sitting on the edge of the bed pulling her socks on.

‘How peaceful it is here,’ she whispers, ‘what a wonderful time you must have had. All I can hear are the birds.’ She looks at me long and hard. ‘Thank your lucky stars you were able to come here, you look so well. Back in Amsterdam we had a horrible time. Aunt Stien’s little Henk is dead, and Mijnheer Goudriaan as well. Thank goodness, darling, all that horrible business is over now. Won’t Daddy be surprised to find you looking so well!’

We walk around the house and I show her everything, the sheep, the little plant I sowed myself under the window, my collection of pebbles. As for the grave, I think, I’d better not show her that, because a little bit of her is buried there. My prayers have changed now and the grave feels different as well: it is as if all the cornerstones of the life I have built up here have caved in.

‘Look, that’s where Jan lives.’ I point across the sunny landscape to the group of trees in the distance. I recall with surprise how long ago it was that I used to stare across to those trees, sometimes day after day, longing for Jan and weaving fantasies around him.

Her bicycle is leaning against the wall at the side of the house, old and rusty but with real tyres. ‘Daddy got those from a colleague at work,’ she says, ‘especially for our trip. But they are old ones, let’s just hope we don’t get any punctures on the way back.’

I walk round it and touch it. So I shall be leaving Friesland on that. I look inside the pannier bags hanging from the carrier, and see that they are empty. ‘That’s where we can put your bits and pieces. It’s easier than a suitcase. We’ve got quite a long way to cycle.’

After breakfast we go and see Jan. During the meal Pieke had stood right next to my mother the whole time, fondling her and clamouring for attention. She had admired everything, the dress, the shoes, the watch, and by the time we went outside the two of them were as thick as thieves.

‘If we go on the bicycle, she can come along too, on the back,’ says my mother, but I insist that we walk and that we go alone. Suddenly I feel that I don’t want to share my mother with anyone else. We walk along the dyke, and near the spot where the car had parked she says, ‘Is the sea behind this? Let’s have a look!’

She runs up the dyke and spreads her arms out wide. ‘Wonderful,’ she shouts, ‘oh, isn’t this wonderful!’ The wind blows her yellow skirt up as she comes flying through the grass. ‘Come on,’ she says, ‘I’ll race you.’

I do not want to go up the Red Cliff. ‘It’ll take too long,’ I tell her, ‘we’ve got a lot to do still. First we’ve got to go to Jan.’

Jan’s mother is sitting in the front room with the farmer’s wife looking at photographs spread out on the table.

‘Jan?’ The farmer’s wife opens the door to his little room and calls up.

‘He’s probably in the barn,’ says his mother, ‘he’s full of it, he talks of nothing else.’

She shows a photograph to my mother.

‘Just take a look at that,’ she says. ‘You can’t tell from looking at it, but he’s dreaming of cows and sheep. He is set on being a farmer.’ She roars with laughter at the thought. ‘He’s a real boy, that’s for sure!’ she says bluntly, looking straight at me. What does she mean, a real boy?

The farmyard. I seem to be seeing it all in slow motion now; the light over the tiled roof, the stinking yellow-brown manure heaps, the weeds shooting up in corners, the muffled sounds from the stables, it all comes home to me suddenly and I go cold for a moment: am I here for the last time?

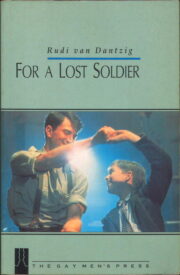

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.