The fields are lifeless, no sound can be heard, and the house is immersed in an ocean of stillness. Inside, too, no one has spoken for a while, the silence broken only by an occasional sigh or a tired yawn.

Night in the country, the day’s work done.

Mem sits by the window, as she does every evening, looking out over the countryside as she knits. Almost no one is about at this time of day, just a few cows or a fisherman still straining his eyes out to sea.

Two people are coming over the Cliff,’ I hear her say. Hait answers the broken silence with an indistinct mumble. I turn over and pick at the scab on my arm. One edge has come away and I try carefully to continue the painful process of levering it off. Just so long as it doesn’t start to bleed again.

Silence, nothing moves, except for the scab slowly coming off.

‘It’s two women.’

I can hear Hait turn his chair around. His footsteps move across the floor and the door gives a sharp creak.

Mem yawns and shifts in her chair. There is the noise of the pump in the shed: Hait is filling his mug. I can hear the gurgling flow of the water.

‘They’ve got bicycles.’ Mem gets up, her voice growing agitated. Hait has come back inside and I hear him put the mug on the table and then drink in slow gulps so that I can follow the course of the water as it passes through his body with funny little sounds.

‘They aren’t from round here, they’re wearing townish dresses,’ the report continues, getting faster.

I push one of the cupboard-bed doors a bit further open and see Mem leaning against the window, one hand over her eyes to see better. ‘What could they possibly want here, so late?’ Hait has moved next to her. The evening sun falls over their faces and lingers on a piece of furniture. Dust whirls in the late light, astonishing quantities of minuscule particles on silent, everlasting journeys.

Why do I just lie there, why don’t I move?

‘Oh, my goodness, they’re turning this way!’

I gather that the two women have left the dyke and are coming in the direction of our house. Two women from the town. My heart begins to thud, an unreal feeling pervades my body.

‘They’re pointing at our house,’ says Mem, now clearly excited, ‘could it possibly be for Jeroen?’

I sit up straight, petrified.

‘Take it easy, man, nothing’s going to happen,’ says Meint and blows his nose noisily.

‘They’re climbing over the fence, they’re either going to Trientsje, Ypes next door, or coming here. Goodness knows which. My, oh my!’

She drops back into her chair, looking like a goddess sensing disaster. Then she gets up, looming large in the low room, and goes to the back of the house. The outside door rattles violently.

‘Could well be your mother come to fetch you,’ says Hait and opens the cupboard-bed doors. I am sitting bolt upright, completely at a loss. There are more voices from the other cupboard-beds and Meint beside me gives a protesting cough.

My mother.

If it is her, then the war is definitely over…

But is it her? Has she really come? Has their longing for me finally become strong enough? My body feels feeble and limp, my belly seems to have dropped to the floor. When I try to take a step, my knees are out of control and I have to cling to the wall in case I collapse.

I can’t believe it and I mustn’t believe it either: I can’t afford to any more, it’s sure to be just another empty hope drifting by like a useless tuft of sheep’s wool.

I stand in the doorway and lean my head outside just far enough to take in the stretch from the side of the house to the fence. Hait and Mem are standing halfway down the path, and when I see that Hait has quickly slipped on his Sunday jacket my knees start giving way all over again: what’s going to happen next? Mem is busy with a lock of hair that refuses to stay in place, her hand patting her head and running down her hip in turns. Seeing her standing there, solemnly, yet on her guard, watchful as if she were about to have her photograph taken, makes my breath escape with a jolt, like a gasp. I am suddenly very aware that the inevitability of the moment has been impressed on everything around: on the gusts of wind bending the tall grass, on the evening sky as it dims to pale grey, and on the expectant silence of the landscape in which the two dark figures have now become motionless. I had tried to steel myself against my own fantasies and dreams, but all of a sudden I have become defenceless and vulnerable, an abject and easy target.

As if sensing that I am hiding in the doorway, Mem turns and looks straight at my face peering around the corner. She takes a few steps towards the house and calls out in an attempt at a whisper, ‘Surely you’re not standing there in your underclothes? Hurry up and get dressed, they’re nearly here.’

I dash back into the room, breathlessly pull my trousers on, wrestle with the buttons and leave my shirt undone.

‘Don’t bother with your socks,’ says Diet, when she sees me bending over. They are all sitting up in their cupboard-beds and are following my frantic scramble with curiosity but also with some awe: I feel that I have suddenly taken the centre of the stage, that tonight I have taken over the main role in the household’s doings, that they are all aware that the denouement of an unfinished tale is about to be played out.

The first thought to spring to my mind when I see her climb over the fence, loose-limbed and youthful, is that she doesn’t look in any way hungry or poor and that makes me feel almost cheated and disappointed. Quickly and apprehensively the two women walk towards Hait and Mem. I can see that they are talking to each other nervously and that they are feeling ill at ease on the grass without a proper road under their feet.

I recognise my mother at once, her movements, her hair-do, her familiar yellow dress. Both of them are wearing colourful summer frocks, billowing out behind them.

Mummy, I think, as the sound of her girlish voice suddenly reaches me. For a moment it seems as if I have lost all control over my muscles and am about to wet my pants. Desperately I squeeze my legs tight together and arch my back.

‘Oh, my goodness,’ I hear Mem say as the slight figure in the yellow dress walks up to her, ‘isn’t this wonderful. So you are Jeroen’s mother.’

Far away on the sweltering horizon I can hear an indistinct threatening rumble, as if the war is still going on, and behind the deserted dyke the sky is a luminous white. The evening is stifling and the air full of dancing mosquitoes. I watch them shaking hands, laughing, their delighted surprise: we have made it, we have found you!

Suddenly, as if on command, all four turn round towards the house. I can hear their footsteps in the grass. If I go back to bed, I think, I might be able to put off having to meet them until tomorrow.

‘Come on, Jeroen, it’s your mother. Here she is now.’ Mem’s voice sounds like a trumpet in the night air. ‘What are you hanging about back there for?’ and she adds in an apologetic tone, ‘He had already gone to bed, Mevrouw.’

I don’t move, pressing myself against the wall. All at once I have become suspicious and mortally afraid of the moment for which I have been waiting for nearly a year. I look down at the floor and keep quite still.

‘He’s never like that normally, is he now, Wabe? He’s a bit shy because everything has happened so suddenly.’

Gently insistent, Mem pushes me towards the back door. I can feel the pressure of her large warm hands as they lie calmly but firmly against my shoulders. Outside stands my mother, a stranger still, somebody I know no more than vaguely and have no wish to know better than that.

‘Hello,’ I say and walk towards her. ‘Hello, Mum.’

She throws her arms around me, kisses me, and then holds me at arm’s length and says in a choking voice, ‘How tall he’s grown, and how he’s filled out! My word, son, don’t you look well, haven’t you put on weight!’

I recognise the catch in her voice, the same pinched way of speaking she used when there was an argument at home and a row suddenly flared up with Daddy.

Don’t cry, I think, please don’t cry, not now and not here.

But she doesn’t cry, her eyes shine and her hair dances in light curls around her forehead. Her joy is something I recognise and it sets off a thrill inside me, as if to drive home to me how strong the ties between us are.

She pulls me back against her once more and this time I am aware of the gentle slope of her belly and the curve of her thigh. The familiar smell of her clothes tickles my nose and brings me closer to home, to our street. I can see the bedroom again, the kitchen, the veranda, the stairs.

Mechanically I put one arm around her, but it feels awkward, artificial. When I turn my head a little I see Hait and Mem standing stiffly side by side in the doorway with lost little smiles, as if they don’t know quite what to do with themselves or about the situation. When I meet Mem’s gaze she nods at me with gentle, helpless eyes and raised chin, as if trying to stifle a sneeze.

And then recognition floods up from deep inside me, a wave that runs through my knees, my belly, my gullet and stays stuck in my throat. My hand makes a few panicky movements and finds a small hole in the soft material of my mother’s dress. I bore my finger into it, a burrowing, frantic finger. I can feel the material give and gently tear.

‘What are you doing?’ My mother’s voice has a sharp, nervous edge to it. ‘Are you trying to ruin my dress? My only good dress!’

She gives a childlike laugh and abruptly pulls my hand from her body. When she sees how crushed I look she bends down and kisses me warmly. How odd to be kissed without the rasping prickles of a beard; it takes me by surprise and I’m not sure if I like it.

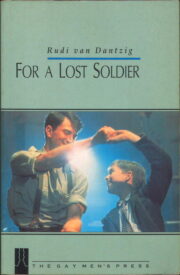

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.