I look away quickly, turn around and put my exercise book down. As I open it and pretend to be giving all my attention to what I am reading, I watch Mem out of the corner of my eye: she is standing leaning across the table, her head turned towards me. I wait, but she says nothing.

‘We’ve been given some really hard sums to do.’ I talk to break the silent tension between us. My mouth is dry and I bite my lips. I have an almost irresistable urge to push her out of the way and to read the writing on the envelope.

When Jantsje and Meint come in Mem sends them out brusquely. ‘Go and play with Pieke by the house,’ she says, ‘or give Diet a hand with the cooking. I’ll call you in good time.’

But I take care to slip out quickly with the others to avoid being left alone with her again. I don’t want to know – let her keep the secret to herself.

I wonder if she has read the letter, if the envelope has been opened. I try feverishly to recall the image of the small white square: what did it look like, had it been opened along the top?

What if it is a letter from home with bad news, a note from the neighbours to say that there is nobody left at home, that they are all dead… But it could just as easily be a letter from Walt, even though he doesn’t know my surname or our address, because all he would have to do is put ‘Jerome, Laaxum, Friesland’ on it and it would still get here, everyone would know that it was for me.

I go rigid. What if she has read it, what if she understands English? Perhaps that is why she’s been giving me such strange looks.

‘Is there enough time to go down to the harbour? I’ll make sure I’m back for dinner.’

Diet gives me a surprised look, she has pulled up her sleeves and wipes her wet hands over her hair. ‘You can see the food is ready, can’t you?’ She puts her head outside the cookhouse and points. ‘The menfolk are on their way now.’

I had wanted to escape, to put off the evil moment. They’re going to have to open the letter without me, I don’t want to be there when it happens. But how can I get out of dinner? Popke and Hait are already by the door, stepping out of their clogs and disappearing into the little passage, leaving behind them a salty tang of fish, tar and wind.

As we make for the table, Hait and Mem stop by the door for a moment and talk together in undertones. I squint at then-faces out of the corner of my eye while my heart beats fast; do they look serious, is it bad news? I dig my fingers into my thighs and move my palms across my trousers. God, be nice to me and help me.

After grace there is complete silence, as if everyone knows that something is about to happen. Hait stands up and walks over to the little chest, picks up the small white patch and carries it towards me. Why? I want to disappear under the table, I am horribly frightened and ashamed. How can I avert this evil moment?

‘A letter has come for Jeroen, from his father and mother in Amsterdam. I think it’s going to be a nice letter.’ When I don’t take it from his hands he puts the envelope down on the table in front of me.

So it’s not from him. Why do I think that, why is that the first thing to come into my head? He hasn’t sent me a message…

All of them are looking at me now, the whole table full of beaming faces, and still there is silence. Should I say ‘thank you’ now, open the letter and leave the room, or should I wait until after the meal?

‘Don’t you want to read it?’ Mem asks. ‘Would you rather Hait read it out to you?’

The white patch flickers before my eyes on the tablecloth, there is an enormous distance between us. Why aren’t I pleased, I think, how is that possible? But what I want is news from him, that’s what I’ve been waiting for.

Suddenly there is a large empty space under my eyes in which shiny flowers begin to take shape, little bunches of daisies, some roses, symmetrically placed garlands and blue forget-me-nots, all sprinkled with the grease spots the oilcloth has gathered over the years.

Hait’s voice reaches me from a distance, hoarse and solemn. I can tell by his tone that he is looking at me and addressing the words to me. I edge backwards until I can feel the back of the chair pressing into me. I hear snatches of sentences, a single word here and there, or a name, but the beating of my blood distracts me and drowns out even Hait’s steadily reading voice.

After dinner Mem keeps me in, leads me to the chair by the window and puts the envelope in my hand. ‘You’d best read it over quietly, by yourself,’ she says and sits down facing me. ‘Oh, my boy, what wonderful news this must be for you!’

The small sheets of paper come rustling out of the envelope. I unfold them and recognise my father’s handwriting.

Amsterdam, it says on top, 9th May. My dear son…

My eyes stop moving. My dear son, is that me?

Is that what Daddy calls me, does he mean me? Is that the eternity that lies between us, the longing, the poignant homesickness? Kiss me Jerome. Is good, I love you. My head rests against his neck and his hands clasp my shoulders tight as if he is afraid I might escape. Say it, baby: I love you. Yes, that’s good, very good.

My dear son,

At last a letter from us. We hope you are well and that you haven’t forgotten us completely! We’ve come though the war all right and now we are free.

It’s taken a long time for us to be able to send you this letter, but slowly and steadily everything is getting back more or less to normal. Bobbie is well, he has grown into a big boy, so you will hardly be able to recognise him. When you left he was such a skinny little baby, but now…!

It is still difficult in Amsterdam to get food, or to get clothes, or shoes. Still, everything is getting a little better, almost every day.

Everybody is very relieved and celebrations are being held everywhere, in the street and at your school. The school is being used by Canadian soldiers now, so you won’t be able to go back there for the time being. You won’t believe your eyes when you do get back! There have been some sadnesses, too, I am sorry to have to tell you. Aunt Stien’s and Uncle Ad’s Henk died suddenly from the cold during the winter and Mijnheer Goudriaan from across the road as well. It’s been really awful for Anneke, not having a father any more. Write her a card one of these days if you can, she’ll be terribly pleased if you do. Mummy and I want to have you back home as quickly as possible of course, but I think it’s best for you to be patient a little while longer until everything is a bit more settled. We don’t even know if you’re all going to be fetched back again, but if not, Mummy or I will come for you, and I think that Jan’s mother will probably come along too in that case. How is he? Please remember us to him.

We have written a separate letter to the lady who is putting you up. You must be very grateful to her for having looked after you for such a long time.

Dear Jeroen, I’ll do my best now to get this letter to you as soon as possible. Just a little while longer, and then all of us will be together again. Be a good boy and give everyone in the family there our kindest regards. They’ll all have to come to Amsterdam soon!

And then, in a schoolgirl’s hand:

Hello Jeroen, Daddy has written almost everything already. We’re having a good tuck-in now with all the things you can get in the shops again, real milk sometimes, and white bread, and powdered egg, it tastes wonderful. Your little brother is turning into a real fattie, he is almost too heavy to lift up. When you get back home you’ll be able to take him walking by the canal, we are trying to get a push chair for him. Is everything all right in Friesland? Mummy.

Is that all? I turn the sheets of paper over. Nothing. Mem has got up and looks at me expectantly. Her eyes are soft and she comes and stands close to me.

The lady who is putting me up.

‘Isn’t that lovely?’ she asks. ‘Now everything is sure to be all right.’

‘Were they liberated in Amsterdam by different soldiers to ours?’ is the first thing I want to know. ‘Ours were Americans, weren’t they?’ I look at her, but she shrugs her shoulders.

‘I don’t exactly know, my boy, you’d best ask Hait about that.’

‘The letter was sent on the ninth of May,’ I say, ‘what day is it today?’

She goes up to the small calendar and slowly counts the days.

‘The twenty-seventh,’ she says, ‘it took a long time getting here.’

I put the letter back in the place where it stood, behind the little vase on the chest.

In the little passage I take my coat off the hook and press my face into the cloth. I move my nose slowly over the sleeves, the collar, the back.

Sometimes it is as if I can vaguely identify his smell, that mixture of metal and hospital, and when I do I am indefinably happy and reassured. But now I can smell nothing, no matter how fiercely and desperately I try.

Without warning, Mem opens the door and gives me a somewhat disconcerted look. ‘Don’t you want to put the letter away in your suitcase? Then it won’t get lost.’

‘No,’ I say. I hang my coat back on the hook.

Chapter 11

The living-room floor creaks, a chair is pushed back, a plate clatters across the table. Meint is not yet asleep, he has a cold and his breath sounds laboured and congested. Outside it is still warm and light, but I can tell from the muted impenetrability of the sounds that the heat is dying down and seeping into the earth.

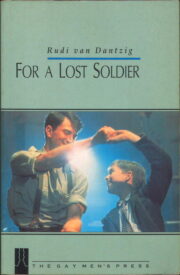

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.