‘Go and fetch us some hay, boys!’ Meint runs back to the barn and throws an armful of fragrant grass onto the ground in front of the cow. She shakes her head stupidly at first, then the tufts of hay begin to disappear steadily into her grinding mouth, nothing else seemingly able to distract her attention. The bull is brought up again, but this time Hettema has to use all his strength to slow him down. He rises up like a furiously rearing horse, the prize-fighter’s muscles so powerful and contorted that we beat another hasty retreat.

A long, shiny spear, scarlet and naked, protrudes from the belly of the rearing animal, a defencelessly displayed sex organ probing and trying to find its way. Dribbling, the bull clumsily seeks support with his forelegs on the cow’s back, while she continues to chew absent-mindedly as if failing to notice that the point of the spear is being pressed quickly and battle-ready into her body. Mesmerised, I watch as the bull, with a vacant, confused expression, takes impatient little steps along the cow’s back, moving jerkily like a lamb tugging at an ewe’s udder. On the other side of the animals, which loom up between us like a mountain range, stand Jantsje and Meint. I meet their eyes, feel deeply ashamed and turn red. Are they laughing at me? I suddenly break into a sweat and my skin starts to prickle. Why are they looking at me like that?

The bull is standing on all four legs again, with what is now no more than a long thread dangling from his belly. ‘Well, that didn’t give him much trouble,’ says Hettema, flicking a cigarette butt over his shoulder, ‘but then he’s an old hand at it.’ He gives a short laugh.

The bull snorts and blows along the cow’s flanks, licking the soiled skin with a caressing movement, showing such devotion and gentleness that I feel myself going weak at the knees and am afraid of falling. Did the bull really go deep inside those elongated, dark folds, into that sticky place he is now licking so quietly and patiently? Was that fucking I had just been watching, the ‘doing nookie’ that the boys in Amsterdam were always whispering and smirking about so mysteriously at school?

The emp’ror of China,

He often fucked Dinah,

It sounded like thunder…

Was that what I did with Walt, fucking? Surely you can only do that with girls, fucking has nothing to do with boys, has it?

‘Go in the barn, I’ll get you all something to drink.’ Hettema picked up a few mugs and poured milk into them from a tin. I look at the manure lying all over the floor in lumps and puddles and think of the sticky thread dangling under the bull. ‘Fresh from the cow,’ says Hettema, ‘full-cream milk, the best you can have. It’s still warm, have a taste.’

The milk rolls about heavily in my mug, little black bits floating on its surface.

…It sounded like thunder,

As Dinah went under.

And didn’t they snigger,

As her belly grew bigger…

As soon as I have the chance and no one is looking, I pour the mug out into the straw.

Jantsje and Meint stay behind to play in Hettema’s yard but I go back to the road and start walking towards the harbour. Pieke, weaving along on her lame leg, trudges behind. Why doesn’t she leave me alone, why does she keep following me, can’t she tell from my mood that I don’t want her company?

I wait for her to catch up with me. Panting because the dyke is too steep for her, she smiles, baring a set of milk teeth full of gaps in a grateful grimace.

‘Did the bull frighten you?’ she asks.

‘Don’t be so stupid.’

What do they all want from me, why do they look like that and ask questions all the time? When we reach the pier she takes hold of my hand, startling me with her touch.

‘Shall we wait until Hait gets back from the sea?’ She careers towards the little beach and hops about collecting pebbles. Sitting at the water’s edge, my arms tight around my knees, I think of Walt, of the leg he threw over me and the impatient thrusts after that. Now I long for those hurried actions that frightened me at the time, I pine for the touch of his belly, of that private, secret place that had need of me. My longing is so strong that it makes me feel weak and ill.

I watch Pieke squat right next to the place where the kitten lies buried. Does it matter if she finds the grave? The paper flower is still there, faded and crumpled now, no longer looking like a rose. Everything else has vanished.

‘I think I can see a boat.’ I am lying, but Pieke hops towards me and peers along my outstretched arm. I stare across the water and fling a pebble into the waves. Plop, a mean little sound, a splash, the beginnings of a ripple and then it is all washed away. I try to picture my mother but I can’t, I am no longer able even to imagine that she still exists. Probably everything has gone, all of them, our house, all vanished in the war, swallowed up in an abyss of horror.

Plop…

I try to pretend that I don’t really care about the letter that doesn’t come, that I almost despise the whole idea. What difference can it make now? And Walt, where is he, is he still having to fight the war? The sea wall he lay behind is across the harbour. That’s where he was waiting for me and where I walked towards him over the rocks. How far away it all seems.

Plop, another pebble…

I don’t think about Jan any more. It doesn’t bother me at all that I hardly ever see him these days, it all seems quite unimportant, a dim memory. The minister’s wife is with God, she can see everything that happens, and perhaps my mother is with her too and they are looking down together to find out what I am doing. I place three pebbles next to the little rose, one for Walt, one for my mother and one for the minister’s wife, in that order.

They are sitting together on a large, grey bench, fused into an ageless whole. Their eyes are not cast down but look out across the mass of grey-white cloud that stretches before them. And yet they see me, they follow me and speak about me, tonelessly, without words.

Are they pleased with the pebbles, have I made them feel more kindly, can I mollify them, win them over?

Bye, angels, I think, oh, angels, bye!

The boat comes into harbour like an all-conquering, dark-brown bird. Pieke shouts and we hop, skip and jump to the landing stage as fast as we can.

While we are walking back home Hait puts his hand on my shoulder familiarly, as if I were a man, a mate of his. ‘Don’t look so unhappy, young ’un, that won’t get us anywhere. You’ll see, there’ll be news very soon, things are happening very fast now.’

I bite my lips. Who will hold me tight, who will take me in his arms, let me feel another person’s warmth? I am dark and dirty inside and out, and that’s how it will always be if his mouth is not there, the tongue that licks me clean, that i ouches me considerately and selflessly, beyond my shame.

‘Pieke, girl, come on, make Jeroen laugh for a change!’

At table I toy with my food and use my fork to make two piles on my plate, intending to leave the bigger one uneaten.

That’s all the thanks we get,’ says Mem. ‘Don’t ask me what’s been wrong with him these last few days. But you don’t get down from this table until that plate is empty.’

‘Lord, we thank Thee for this food and drink. Amen.’ Everyone gets up, while I am still wrestling with myself. The bull’s gigantic body rears up threateningly and yet helplessly, the spear stuck out in triumph like a blood-red flagpole…

I have laid my head in my arms and sniff at the oilcloth on the table. Overhead I can hear a fly caught in the flypaper, a piercing, penetrating buzz. All of a sudden Diet pulls my chair back so that I nearly fall to the floor; the world does a half turn in front of my eyes and my heart misses a beat. I let out a shriek and run sobbing out of the house, across the meadow in my stockinged feet. As I race through the grass I can still hear my scream, a ludicrous yet terrifying cry, echoing in the emptiness that I feel all around.

When I go back home a little later the sheep are standing huddled together behind the fence, looking at me with cold, searching eyes. One of them is smiling at me, pointedly and sardonically.

Chapter 10

Rarely does the postman come out to Laaxum; generally he waits until somebody can take the letters, if there are any, back with them to our small hamlet.

Halfway home on our way back from school we run into him, bending far over the handlebars of his bicycle as he pedals against the stiff wind, and a ray of hope shoots through me, even though I have gradually managed to eliminate all feelings of expectation.

While Jantsje and Meint quench their thirst at the pump, I hurry into the little passage as inconspicuously as I can. The house is unusually quiet, the living-room door is closed and Mem is nowhere to be seen, which is odd. When I push the door open with a gesture of apparent unconcern, she is sitting idly at the table, her hands on her knees and she gives me a strangely gentle look, dreamy and far away. Her jaw makes soft movements to and fro. Is she trying to suppress a smile? Before I can open my mouth she stands up and, as if caught out, starts to move the little framed portraits on the mantelpiece, rearranging them.

I let my eyes run over the room and almost instinctively spot where the change is: on the little chest there now stands a square white envelope, modestly tucked away behind a little vase. There is a green postage stamp in the top right-hand corner, but the place where the handwriting of the address should be is hidden from my view by the little vase.

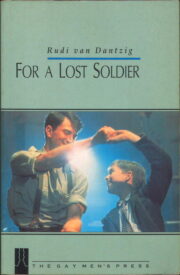

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.