I see a long, coiling fish circling lazily in his head, through his open mouth and in his eyes, feeding and searching with a lisping, slippery tongue and sliding through the torn, white vest. Where his hair used to be, green, slimy seaweed waves about, and his chest moves, rising and falling, in and out…

I stare into my plate at the indefinable morsels and narrow my eyes to slits. Don’t start crying now, go on eating, if I don’t do any chewing, and swallow very quickly, then I won’t taste a thing.

‘It’ll take two weeks to turn into a skeleton, we’ll keep on looking and see how it happens.

Back to school again: Walt will be there, he’s waiting, of course he’s there, he waves and smiles without a care in the world. Nothing wrong!

The afternoon heat scalds my throat and eyes making me feel sick. I must go to bed; my blood is beating in my throat and I can’t move. But I have to get to school, to the village, where he will be sitting relaxed and patient in the car, where he will lift me up, touch me, fondle me. we thank you. v = victory… I have to get there. Come along now, you lot, don’t dawdle, keep walking, honestly, that gull hasn’t changed yet, we can look at it tomorrow. Keep walking, or I might miss my lost soldier…

The village is empty and hot, the road stretching lazily

between small gardens with shrubs in bud and young plants flowering profusely. A goat bleats like a plaintive child and a cat crosses the road slowly, sits down and licks its fur, one paw extended high in the air.

The church, the crossroads. But there is no car outside the school.

‘We thank Thee, Lord, for granting us good health this day in one another’s company. Forgive us our sins, of which we have a multitude, and help us to confess our misdeeds.’ The master walks to the door and holds it open for us.

And suddenly I am sure they must know all about it at home, that they are angry with me and that my last foothold is about to splinter under me.

‘Go away, get out of here, we detest you, you and your townish ways.’ They have always known about it and have simply been biding their time. Now they will pack my suitcase and put me down by the dyke. And they are right, I am disgusting, I am a sinner, I am sure to go to Hell. I shall be punished, tormented…

As I sit by the window and look at the birds still flying about in the cool, noiseless evening air, Mem brings me a mug of milk. She pats my cheek and says, ‘Don’t fret, my boy, everything will turn out just fine. You’ll be getting a letter from them any day now, I think the post in Amsterdam is working again.’

I wake up because my body is shivering, my limbs shaking uncontrollably. I press myself flat into the mattress and clench my teeth. Beside me Meint is sleeping the calm, docile sleep of the young. I stare into the dark, but it stays black and void, his face, his voice, his smell, not reaching me, no matter how desperately I seek them.

Next morning I fold my shirt carefully with the breast pocket turned inside and quickly store it away in my suitcase. I do not so much as glance at the small photograph.

We go back to school and once more I run ahead of myself, up the road and through the village to the crossroads. But each day my haste seems to lessen and I slow down: I seem to be marking time and quite often freeze into immobility right in the middle of running.

I realise that it is all in vain, my hurrying, my hoping, my waiting. He has gone.

Chapter 9

The sheep behind the fence look at me with chilly, inscrutable eyes as they scratch their fleeces against the fence; one of them appears to be giving me a sardonic smile, chewing continually with its mouth askew. I have to turn my eyes away: does everyone know my secret?

I pretend to be reading, but my eyes see neither the words nor the lines, just a dazzling bright spot that shimmers and glitters in front of me. Everything appears faded and washed out: the sleeves of my pullover, my socks, the reeds beside the ditch.

From the other side of the house comes the dull, thumping rhythm of a ball bouncing against the wall; every time I hear the sound it is as if somebody were banging away persistently in the middle of my head. I look at the hundreds of letters making up the sentences and flick impatiently through the pages of the book. I must read it properly and not keep thinking of other things.

He has been gone for nearly two weeks now and with every passing day he is hundreds of miles further away, his distance from me growing unimaginably great. Is he thinking of me, is he planning to come back? At first I was convinced he was, but now I am no longer certain. I pluck a dandelion from its stalk and the milky sap that wells up out of the little ring leaves black marks on my fingertips. Then I pull off the yellow petals and reduce them to a few sticky, powdery wisps between my fingers.

The thumping behind the house has stopped to make way for an ominous silence: why aren’t they playing any more, are they about to come over here? The small bouncy ball, a construction of orange rubber bands wound tightly round each other, flies past me, rolls through the grass and comes to a halt close to the ditch. I quickly bend over my book.

‘Are you still sitting there?’ While Jantsje runs after the little ball Meint leans over me and says, ‘Still on page twenty-one, I see. Haven’t you got anything better to do with your time? Come on!’

I turn over a page. I can hear them snigger and whisper conspiratorially behind my back. Why do I always feel so tired these days, with that empty, sick feeling in my body that doesn’t want to go away?

‘Come over to Hettema’s with us, just wait till you see what’s going on there, it’s fantastic…’

The sheep are walking alongside the ditch now, their feet sinking in the mud, so many round balls of wool stuck onto four brittle little sticks. Soon they will be shorn and thin as dogs, then it will be my turn to smile sardonically and chase those nosy riffraff all over the countryside. Stupid creatures.

I allow myself to be pulled up from the grass, but then Mem’s voice rings out from the house. ‘Jantsje, you aren’t going anywhere. Pieke’s always being left here all by herself, none of you ever give her a thought. Either she goes too or else you are all going to stay right here.’

‘Make her hurry, that’s all, we’re not going to wait for her, everything takes ages when she’s around.’

As if to prove how quick she is the little girl hops lickety-split through the grass, tossing and flailing her arms about, her callipers clattering over the tiles that serve as a path through the meadow. She stops out of breath by the fence and stands there waiting until we heave her impatiently and roughly over it. On the other side, in the lee of the dyke, lies Hettema’s farm, surrounded by tiny fishermen’s cottages like a big mother hen ruling over her roost.

‘Come on, you lot, hurry up or it’ll all be over!’ We run through the sheets of mud in Hettema’s yard towards the stables. A large animal stands four-square on a narrow path behind the barn, two men keeping it under control. The beast grunts protestingly and shakes its enormous head, making a jingling sound.

‘Albada’s bull from Warns,’ Meint whispers, ‘he could go straight through a wall if he wanted to. Just look at those legs!’

The soft nose, wet and dripping slime, has a thick iron ring stuck through it on a solid chain that one of the men is pulling while the other beats the animal’s flanks with a piece of wood. ‘Get moving, blast it, you lazy devil…’

Hettema is standing by the cowshed. ‘Not behind the beast, Meint, get the children away from there, he can turn nasty.’

Goaded, the bull turns its head from side to side in soundless protest, then lets out a bellow as if maddened by pain. I can see a streak of blood in the slime from the nose and cringe suddenly with every blow I hear. I’m not going to stay here, I tell myself, I’m going back home.

Then the bull is thwacked on its hindleg and moves forward reluctantly, meandering along the narrow path. Meint grips my arm. ‘It’s all right, it’ll all be over in a minute. And they don’t feel that hitting at all.’

They’re going to slaughter the bull, I think, fascinated by that large chunk of life that for mysterious reasons will suddenly cease to be, like a storm that dies down in the twinkling of an eye. In Warns I once saw them slit a cow’s throat: a sure, razor-sharp movement of a piece of steel across the soft skin, the eyes turning surprised and glassy, before a moment of dazed silence, and then, suddenly, a gush of blood and the huge body caving in as blood and shit spattered up the walls. I was frightened that time, going rigid with revulsion and yet I didn’t avert my eyes for a single moment.

As the bull stamps rebelliously past the barn Pieke and I watch from a safe distance, our hands excitedly clasped together, while Jantsje leaps to and fro, nervous as a hare.

‘The cow’s over there,’ says Meint solemnly. ‘Now you’ve got to pay attention, that’s what the bull has come for.’

The bull is brought round behind the meekly waiting cow, stays standing for a moment stock-still, then heaves his unwieldy, leaden body up onto the thin, tottering hindlegs, snorting violently as if under enormous exertion, and places his front legs comically on the cow’s back.

‘He’s dancing,’ laughs Pieke, ‘can you see, he’s going to do a dance!’

Meint pushes us anxiously along the wall to the front. ‘Otherwise you won’t see a thing.’

The animals take a few clumsy, stumbling steps as in some primitive fox-trot, until one of the cow’s legs slides off the path into the mud and the bull loses his balance and falls back onto his own legs. For a moment there is nothing but angry bellowing – we have all run away giggling nervously – then the cow starts to trot about impatiently, her udders swaying under her stomach. Where the path meets the fence she tries to turn round, but the men have already grabbed her by the head.

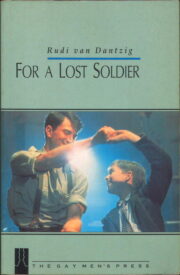

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.