I peer over at his exercise book and see two pages covered with writing.

‘When we heard the war was over, I walked…’ It looks as if I shall never get beyond these few words and I read the unfinished sentence over and over until I feel I’m going mad. I run my finger over the WI have scratched with a nail into the corner of my desk: there is nothing I need write beyond that W; it is my whole liberation story.

I can hear the loudly tapping feet of a bird hopping angrily to and fro in the gutter. After a short silence, seemingly to catch its breath, it starts to whistle: gently swelling notes that turn into excited twittering, now high, now low, as if it is choking on its own passionate sounds.

I lean my head on my hand and shield my eyes. The pencils continue to write. Whatever can they all have to say? I look for a handkerchief and blow my nose. It presumably wouldn’t do to burst into tears about a composition that refuses to come.

When the master collects the exercise books he leaves mine untouched.

‘I am curious to find out what you have to say about the past few days, to read what is bound to be a wonderful record of this unforgettable time.’ He coughs solemnly. ‘From now on everything is back to normal, the celebrations are over, but when, in the future, you re-read your compositions, these days will again shine bright before you. Our liberators have other duties, they will be leaving us now, but we shall never forget what they have done for us…’ Silence and a penetrating look. ‘They have rid us of a curse, the Lord has sent us help just in time. If ever you are at your wits’ end and no deliverance is at hand, do not forget, God does not abandon you. How true the words of the hymn are.’

I brace myself at my desk, spent, squeezed empty.

‘Let us therefore pray.’

A little later I hear the voices fade away across the school yard. I am sitting alone in the classroom, forcing myself to put down one word after another, making short sentences that are stupid and meaningless: it doesn’t matter to me as long as there’s something.

The master comes in and draws a curtain to keep the sun off his desk. He leafs through the exercise books and yawns.

…‘Stop now,’ I hear him say, ‘just bring me what you have done.’

Punctiliously, his eyes follow the lines I have written. ‘Later you will realise what momentous events occurred in these days, and then you will be ashamed that you could find so little to say about them.’

I look at the dry hand shutting my exercise book. ‘Pity,’ he says, ‘truly, I feel sorry for you.’ He walks before me through the door and holds it open for me affably. ‘Is everything all right at home? Do give Akke my kind regards.’ Taken aback by his genial manner, I walk along the corridor by his side. ‘No doubt you’ll be going to join the rest at the bridge, the whole class went there I think. But all of them will have gone by now, of course.’ He locks the outside door carefully. I cross the little yard. It smells of summer in the village, you can almost hear the trees bursting into bud and growing.

‘But all of them will have gone by now, of course…’ What did he mean by that, why does that sentence keep sticking in my mind? Reluctantly I walk towards the bridge, Meint is sure to have gone straight back home, why don’t I do the same then? Hadn’t I made up my mind never to go there again?

The people in the village are sure to have seen through me long ago: ‘There he goes, off again to the soldiers, what do you think he can be up to there?’

I feel more and more anxious, and slow down. Shall I turn back? A farm cart overtakes me, I run after it and hang on to the tail-board, hoping it will get me there more quickly.

The cart stops by the canal. I jump backwards from it, out of breath, take a few steps to the edge of the water and stand stock-still. The light is overpowering. Across the canal lies a cleared and trampled-down field. Wheelmarks run through the grass and it is easy to tell from the flattened areas where the tents used to be.

What have they done, what has happened? I run across the bridge and up the road: their cars must be parked somewhere. The fields are bare and empty. I stand still, then run back, hollow footsteps over the bridge and strange sounds in my head. People in the street turn around to watch me race past. My thoughts spin furiously upon a single point until I turn giddy and fall. Blood runs from my grazed knee. I race up the road to Bakhuizen, stop suddenly, and race back, a well-trained dog.

The bridge and the spot where the tent had stood: in a frenzy I chase around in circles, an animal looking for a prey that has vanished from sight. There has to be a sign, a note, a letter with some explanation, an address… I have been left no name, no country, no destination, neither his smell nor his taste… I feel panic, smell fear: where are you, where am I to go?

The blue sky, birds tumbling and calling. Untroubled.

God, I think, You were going to raise me up, You were going to help me. Oh, God, together we were going to perform miracles…

Where his tent stood there is now a square in the grass, a flattened shape of bent stalks and trampled-down flowers, a clearly outlined, life-sized sign. I run over to it and kick my foot into the grass, claw at it, digging, finding nothing but a rusty, bent fork.

Go home, I think, he’ll be waiting along the road, of course.

Winding broadly, the road runs through the summery landscape to Laaxum.

Chapter 8

I move the bar of soap between my hands and then lather my forehead and neck. I look at my face in the slanting little mirror, a normal face with small, tired eyes, sleepy and drained white. I can no longer see traces in it of the anguish, the terror and the despairing rage that seemed to turn my eyes to stone, emptied of tears, hard and dry as if stuck together with clay so that they would not open in the morning.

I can hear voices and footsteps in the cookhouse, the creaking of the pump, and I feel an arm nudging me: ‘Get a move on, it’s our turn.’ I am here and I am not here.

The hard-ridged pattern of the coir matting bores into my feet and the ice-cold water etches tingling spots on my face. I lean closer to the mirror: are there really no tell-tale signs left of my laborious breathing, of the hollows around my eyes, of my panicky distress? I curl my toes and move my feet in little circles over the matting.

When I put my shirt on I feel the flat little place on my chest where his photograph is. I don’t take it out because I know for certain that he will never come back if I look at it now. I must be strong and wait.

At table they all talk and laugh, everything is as usual. I force myself to eat the bread and butter which piles up in my mouth, turning into a solid gag. Take a sip of tea, swallow, work it down, another sip; all is well, no one seems to notice anything. Is okay, Jerome, is good…

Of course he hasn’t left, he is in the village, waiting in the car: suddenly everything inside me lights up and I feel a sense of freedom and relief. He is sitting behind the wheel, waiting for me to come. I must hurry to school before he goes… Come on you lot, get that food down, don’t dawdle, can’t you see I’m waiting, that I’ve been ready for hours? Come along, hurry up, please, before I miss him, do hurry up, I’m in a terrible hurry…

Meint and Jantsje are still a bit sleepy and take their time walking to school through the countryside, breathing in the cool morning air and stillness. They chat and laugh and I feel forced to join in. We stop for a long time beside the twisted body of a dead gull at the side of the road, its rigid claws sticking up into the air. Walt, I think, don’t go away, I’m just coming, I’ll be with you in a moment.

Why don’t I go on ahead, why don’t I run, why do I hang about with them meekly instead? Meint shoves the gull over the edge of the ditch with his clog. ‘It’ll take two weeks to turn into a skeleton,’ he says, ‘we’ll keep on looking every day and see how it happens.’

We walk on, a bit more quickly now, but in my thoughts I am racing ahead, careering up the road, flying to the crossroads, to the church, to the bridge. He is sure to be there, somewhere not far away, my patiently waiting liberator, and everyone will see me step into his car. I shan’t be ashamed, not even when his puts his arm around me. We shall drive off and leave the gaping villagers behind and I shall hold tight to his jacket and never let go again.

At lunch, Mem puts a dish on the table with a gigantic, furiously steaming eel laid out on it. It is pale and shiny and the thick skin has burst open revealing its greasy, white flesh. The smell of fish hangs heavily in the small room, seizing hold of me and clinging to my nostrils, mouth, skin and clothes. I shiver.

Hait slips a long knife along the blue skin, splitting the hideous bicycle tyre into two steaming wet halves. I reluctantly hold out my plate. Hold it, yes, go on…

‘They eat corpses,’ a fisherman in the harbour had once told us with a laugh as he emptied a bucket of squirming eels into a crate. ‘They crawl into anything lying dead at the bottom of the sea and suck it dry.’

It lies steaming on my plate, the potatoes swimming in a white, watery fluid with yellow islands of fat floating on top. Mem is proud of her big fish and looks on anxiously to make sure that Hait has given everyone a good helping; I am going to have to eat it all up or she will be angry.

Walt is suspended upside down in the water, his round, muscular arms relaxed as they float above his head, moving gently in the sea current. He has a wild, distant look in his eyes and a mouth like a fish, wide open, as if he wants to scream. But all sounds have been silenced.

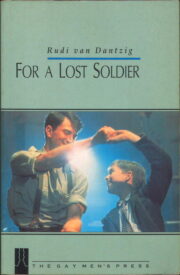

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.