I turn that thought over and over, chew it and chew it again.

Outside, the farmsteads have been as good as swallowed up by the dark and an alarming red glow has traced a fiery tear on the horizon. Suddenly I feel cold and when I try to move I realise that I have grown stiff.

I shiver, as if I have just woken from a bad dream. Of course it is good to be here, I like this tent and Walt is my friend. If I go away with him he will look after me well.

Everything will be all right, then.

From the house we had continued along a different road; so now it was going to happen, my journey into the unknown had begun. But the start hadn’t been very pleasant; Walt had said almost nothing, all he had done was yawn every so often and then smile apologetically. I wondered if he felt the same as me. My body seemed to be a jumble of separate parts that had been pulled to pieces and then thrown haphazardly and painfully together again. Was that why he was being so unfriendly?

But then, unexpectedly, he had seized me roughly and pushed my head into his lap. Now and then his hand would slip down from the wheel and move over my face which made me feel less uneasy. Where were we going, how far had we come?’

‘Come.’ I had heard the car slow down and from his movements I had understood that I was to sit up. When I had looked out I was confused, but then I recognised the tents and the camp and the bridge beyond – it was just that I was approaching them from a different angle. We had come round in a circle to the same place.

The first thing I had felt was disappointment: so we were back in Warns after all. But perhaps it was only for a short while, perhaps Walt had things to settle before we left.

We had walked to the big tent where a few bored soldiers were sitting at the table. One of them had poured us coffee and while I finished off the tepid liquid that tasted strong and bitter, gulp by gulp, I had listened to the sound of their voices and tried as hard as possible to be one of them, sitting on my chair like them, leaning on the table and drinking from my mug just as they did. The more everything was done like them, the better.

A little while later two of them had dragged a large crate from under a tarpaulin and carried it to the car. Walt had started to walk with me towards his tent, then stopped and pointed to it.

‘Wait there.’

As I walked on I saw him go towards the car, a bag over his shoulder. He stopped for a moment and waved his arm. ‘Go in!’ It had sounded brusque, like an order, and obediently I had opened up the tent and slipped into the quiet, warm little space that was both tidy and empty.

Later he had come in, changed his shirt for a clean one, squatted down for a bit and then gone out again.

‘You wait. Me…’ He had mimed bringing food up to his mouth and pretended to chew.

‘Jerome wait. Okay?’

He had placed a finger to his lips and given me a conspiratorial look.

‘Good boy.’ It had sounded like praise and approval and had banished my feelings of disappointment. Even when he had been gone for a long time I hadn’t dared move, had touched nothing and waited.

When he throws the tent flap back it is almost completely dark outside. For a moment it is as if he is surprised to find someone there. Had he forgotten me or had he expected me to have gone? Then he puts down an apple for me and tears the wrapping from a bar of chocolate, rolls the sleeping bag out and sits me down on it.

The smell, the odour of metal filling the tent!

He crawls in behind me and speaks in a lowered voice while he looks for something in the dark. Stopping what he was doing he puts his mouth to my neck. But I don’t move, just sit there motionless, waiting.

He lies down beside me, breaks off a piece of the chocolate and carries it to my mouth. ‘Eat. Come on, eat!’ He is whispering and yet his voice sounds loud. I grow giddy with the sweet taste that floods through my body, with the smell of his clothes and with his caressing hand on my knee. I feel as if I am softening and melting like the chocolate between my fingers: this is the way I want to live, of course, so long as he is there to fill the tent with warmth and smells and food.

He looks in the side pocket of the tent, rustling envelopes and paper, switches his torch on and shines it on something he is holding in front of me.

It is a photograph of him standing with his arms folded across a blue check shirt, leaning against a wall. I recognise his watch. He pushes the photograph into my shirt pocket and pats it.

‘For you. Jerome, Walt: friends.’

He pulls me towards him and I disappear into his arms.

Feeling a heaviness in my eyelids, I slowly start to doze off. Outside I can hear a soldier talking softly and somebody seeming to hum an answer, everything sounding vague and far away. Are we going to sleep now?

He loosens his belt, picks up my hand and takes it inside his clothes. Why doesn’t he leave me alone, can’t he see how tired I am? Will it always be like this?

Soft and curled up, the thing lies sleeping contentedly under my palm. I touch it gingerly, afraid to wake it up. The sleeve of Walt’s jacket presses against my eyes and sleep overwhelms me.

‘Don’t stop.’

The murmuring voice sighs in my ear. I am stroking it, aren’t I? Wearily I notice that the silkworm, as if scenting danger, is beginning to straighten, suddenly springing upright, like that dog I never dare touch in the village.

‘No, hold it. Move.’

I move it.

‘Don’t stop.’

I don’t want to any more, I am tired, we must go to sleep. The thing stands on stiff, threatening paws. Its upper lip is drawn back, the hairs on its back bristle and it bares shiny yellow fangs…

‘Faster, yes. Do it.’

…and utters angry and repulsive sounds.

I bury my face deep in Walt’s sleeve until he lets go of my hand and I can hear him moving about in the dark. Then everything is still.

The quietness takes me by surprise. It is as if I have been left alone in a deserted, empty room. But Walt is close by: the pressure on my shoulder is the arm he has thrown across me. Are we going to sleep with our clothes on, and without any blankets?

When I hear whispers and suppressed laughter outside I have to use great effort to force my eyes open. Walt sits up and pulls his sleeping-bag over me. The childrens’ voices are close by, I can hear their smothered sniggers. Then a corner of the tent is lifted up and I see the smudge of faces bent down looking under the canvas.

Who are they, do they know me, do they know that I am here? But it doesn’t matter, I’m leaving here anyway, they won’t ever see me again…

When Walt leaps up and shouts something at them, they run away, a flock of excitedly cackling chickens. He crawls outside and sticks a peg back into the ground, talking meanwhile to some soldiers in another tent. Then he sits down beside me and turns on his torch: one side of the tent is hanging in loose folds. We wait and listen. I can hear his breath and the beating of his heart. The crackle of a small radio comes from a neighbouring tent.

‘Okay,’ he says, ‘baby.’

He leads me in the dark along the ditch. I stumble over holes and rough ground as if sleep-walking. He holds my hand tight, which surprises me, here where everyone can see us even if it is dark.

He stops close to the road and winds my hair round his finger until it hurts. What are we going to do now, where is the car?

‘Okay,’ his catchword, ‘sleep well.’

He gives me a firm slap on the bottom and pushes me up the road.

Whistling softly, he walks back, his feet moving audibly through the grass. I watch his shadow move past the faint circles of light shining in several tents, then it disappears.

I walk to the bridge: and I had thought that I would be staying with him, living with him in his tent, sharing his mess-tins…

The village is quiet. I can see people behind lit windows.

The ditch beside the road has a black and oily sheen. If you didn’t know any better you might have mistaken it for a path you could walk on, so solid and firm does it appear. Above the dimly glowing horizon is a venomous, thin little moon, a trimmed fingernail.

What shall I tell them at home? This is the first time I have missed the evening meal.

But in my heart I know that I am never going to go back. I shall carry on walking and no one will ever see me again. I shall carry on walking until I am back in Amsterdam.

Chapter 7

The master clears his throat noisily and gives a pointed cough. I start and look at him: the cough is definitely meant for me. His eyes are fixed on me as if he can sense that my thoughts are not on the composition.

‘That’s quick,’ his voice is mocking, ‘for once you actually seem to be the first in class.’ He walks up to my desk and swivels my exercise book around: again that disapproving look. As if in disgust, he guardedly turns a few pages over and gives me a questioning look. He is wearing an orange rosette in his jacket, a favour that does not suit him.

He could be nice enough when he needed me to do the drawings, I think, but now…

He turns the exercise book back to me abruptly and stalks off to the front of the classroom. It is stifling inside the room, the heat of the sun seems to release the smell of children’s sweat and of stables from our clothes.

I bend over the paper and try to construct a sentence. I can still feel the master keeping an eagle eye on me and I break out in a sweat which dampens my hair and then starts to trickle down my back. Grimly scratching my head, I write two words. ‘…I walked…’ My hand falters, again the pencil is suspended lifelessly above the white paper. All around me pencils are scraping steadily away and now and then a page is turned over with a rustling sound. The boy beside me raises his head: ‘Finished, master.’

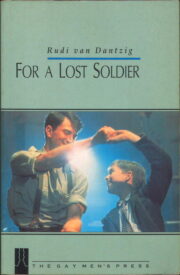

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.