We wake up with a start. The tail-board has banged open and a few of the suitcases have fallen out with a crash; I can hear them sliding around the road.

There is crying. A few children stand up confused and are pulled back down again. We thump our fists against the cab, but the driver keeps going. Outside it is pitch-black.

The lady leans out and swings the tail-board back up.

It could have been my suitcase, I think. No more underwear, no towel, no socks. Have I still got my registration card?

I feel in my trouser pocket. Jan’s arm slips off me. I must remember to keep my hand on my registration card, otherwise I’ll lose that as well.

The driver drives over the Dam with dipped headlights. That I ceaseless murmuring is the sea. A gull drifts over the road like a scrap of paper and disappears into the dark. The lorry is a mole burrowing through the night.

All the other children sleep, like animals seized with fear. I heir bodies shake in unison at every bump in the road. Only the lady is awake. She stares at the flapping canvas with mile-open eyes.

Chapter 2

Dishevelled, our faces grubby and apprehensive, we huddle together in the morning mist. Two hulking men have lifted us out of the lorry and now we are waiting, expecting the worst.

Jan is sitting on his suitcase, staring at the ground, yawning without stopping. No one says a word.

The lady and the driver have walked away from one end of the lorry. What are they talking about?

We are at a crossroads. I can see quiet country lanes disappearing in three directions. The village stretches out on two sides: small houses, little gardens, a church. Not a soul is to be seen, everyone is asleep.

The road in front of us disappears into dank pastures where the motionless backs of cows stick up out of the mist like black and white stones in a grey river. Is this Friesland? Surely it can’t be.

‘Friesland is one of the northernmost provinces in the Netherlands’, I was taught at school, which would make me think of frozen white mountains and snow-fields. The North Pole, Iceland, Friesland: they all conjured up a cold and mysterious image of icebergs and northern lights, of unknown worlds benumbed with cold.

But where we are now is just like those outskirts of Amsterdam that I would see when I had a day out bicycling with my mother and father during the holidays: green trees, a village street, small houses with low-pitched roofs, absolutely nothing to boast about later in our street back home.

But perhaps this is only a stop on the journey, a short break on the road to our mysterious destination. Several men come out of a gloomy little building with a pointed gable, something halfway between a church and a storehouse. Country people because they are wearing clogs.

They talk in low voices and walk unhurriedly, ponderously, towards the lady. One of them holds the doors of the little building open and beckons us: we are to go inside.

It smells damp in the building, musty, as if no one has been in it for a long time.

Warily we shuffle across the wooden floor and sit down quietly on the narrow benches lined up against the walls. The room is high and bare. There is a bookcase with rows of Hue-jacketed books and folded clothes, and hanging on two 11| the walls are rectangular slate boards, one of them chalked with mysterious letters and figures:

PS. 112:4 R. 8 + 9

I wonder if they have something to do with us. Perhaps they are check-marks to be entered on our registration cards so that we can always be identified and traced.

High up on the walls small windows in cast-iron frames let in a little dim light. I look at the row of bent backs on either side of me. There is some shuffling of feet and a bout of hoarse coughing. Jan is sitting some distance from me. He doesn’t move but his eyes are following the lady, who is being excessively busy with the luggage. She shifts and rearranges the suitcases as she notes down on a sheet of paper how many have already been brought in and which ones belong to whom. From time to time she looks at us thoughtfully and bites her pencil.

She is sharing us out, I think to myself. I must go up and tell her that Jan and I belong together, that we’ve got to stay together.

‘You’ll be given something to eat in a minute.’ She points to a table where a pile of bread and butter is lying half-hidden under a teacloth, beside a tin kettle.

‘As soon as you’ve eaten, you’ll be taken to your families. There is one for each of you here in the neighbourhood.’ What does she mean? All of us look stunned or half asleep.

She pushes two bags to one side and crosses something out on the list. ‘You are very lucky that these kind people are willing to take you in, so be on your best behaviour. They speak Frisian here, it’s hard to understand.’

She makes an attempt at a roguish laugh and pulls a childish face. ‘At first you’ll find you can’t make head or tail of it, I can’t understand half of it myself. But in a month’s time you’ll be speaking it really fluently, just you wait and see.’

We stare at her blankly, as if her words aren’t getting through to us. Why is she laughing, why are we having to sit here all this time?

I can see my suitcase, somewhere at the back, so it’s still there. But really I couldn’t care less, what does a suitcase matter?

Jan has already been given his food and is holding a mug of milk between his knees. He hasn’t spoken one word and looks straight through me, as if we had never known each other or even lived in the same street together. But I couldn’t care less about that any more.

A few men are standing round a table by the door. As they talk, they look at us and point or nod in our direction. Then one of them buries his nose in a writing-pad, as if he is doing a complicated multiplication sum.

One man points his finger at the paper while looking at us out of the corner of his eyes. Then he lifts the fingers of his other hand up, counting: one, two, three… When it won’t work out, he starts all over again: one, two…

We eat our bread and butter in silence, peering over our mugs as we drink our milk.

The driver sits a bit further back on a chair. He has a small pile of bread in front of him and chews steadily, looking peevish and disgruntled.

I have a plan. I’ll go straight up to him and ask him if the lorry is going back again, and if I may go along too. No one will notice if I disappear. I’ll save my bread and butter and if I give it to him he’ll be sure to let me. I look around: what am I doing here in this stuffy; dark room? Why did I ever allow myself to be taken to the lorry? I should have run away while we were still in Amsterdam. I am filled with regrets.

I picture the driver suddenly, giving me a friendly smile as he takes me along with him to the lorry. Unnoticed, we’ll start it up and drive away. Escape!

But I know that I shall go on dutifully sitting here waiting to lee what they will do with me. The driver stands up, talks to I the men by the table and unexpectedly walks out. Too late. I’ll have to think up another plan…

The lady takes the first two children by the hand and leads them out like animals to the slaughter. Everyone left behind stares after them.

They have no luggage with them: so it must have been their suitcases which fell out of the lorry last night. Outside the door we can suddenly hear loud crying and the furiously scolding voice of the lady. I can feel all the children in the hall growing smaller, terrified at the sound.

The silence that follows has something threatening about it and there is a strange tension between the adults and the children. The men stand close together. They seem to be uniting against us. Are they likely to hurt us, can we trust them? They talk in hushed voices and not one of them has a smile. They look at each other worriedly and then at us, as if we are an insoluble problem.

Greetje from Bloedstraat is part of the next group to go. She smiles at me with the corners of her mouth turned down, lop-sided like the limp bow in her tangled hair. She makes an almost imperceptible movement with her hand: bye.

Next it’s Jan’s turn. When the lady calls out ‘Hogervorst’, he picks his case up firmly and walks to the door. I follow him with my eyes. ‘If we just stay together,’ Jan had said. Now he is leaving the hall without even sparing me a glance.

Slowly but steadily all the children disappear. I am the only one left behind, just like what always happens during games at school when the boys pick who is going to play in which eleven.

It doesn’t surprise me, I never get picked, it’s all part of the same misery. The men look at me from behind the table; the papers come out again; there is a brief discussion. The lady shrugs her shoulders and looks at her watch. ‘According to the list you should have been a girl,’ she says impatiently, walking over to me. ‘They’ve made a blunder somewhere as usual. Nothing we can do about it now…’

I pretend to understand, smiling vaguely.

When I am suddenly told to stand up I feel a blinding fear. Stiff-legged I go over to my suitcase and walk out of the door. All their eyes are on me and I have the feeling that everyone is breathing a sigh of relief.

Before I know what exactly is happening, I am sitting on the back of a man’s bicycle, too scared to hold on to his coat.

In my terror I have failed to take a last look at the lady and the driver, the last people known to me. All at once I feel I can’t do without them, now that I am being left alone with this silent man who is pedalling away with his back bent against the wind. We leave a village street behind and then bicycle along a road that curves through sloping pasture-land and past quiet farmhouses. Here and there cows or sheep huddle sullenly together, their shapes reflected in still ditches.

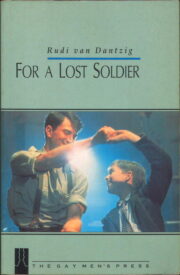

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.