‘Got it! Come on, now we can go and catch some frogs.’

If we go back home I shall never be able to get away. I take the tin and, lying on my stomach, scoop up some water with it. ‘It leaks, it’s got a hole in the bottom. It’s no good.’ I try to fling it into the water, but Meint snatches it out of my hand.

‘Don’t be stupid. I can easily mend it with a bit of tar.’ He makes for the shack and disappears behind the banging door. Instead of following him I race past the little building up a grassy slope, drop into a hollow and press myself close to the ground. Meint calls out, first round the back of the shack and then towards the side where I am lying hidden. ‘I can see you. Come on out, I’ve mended the tin.’

Why don’t I go along with him, catch frogs and play by the ditch? I have to stop myself from raising my head. When I hear the sound of his clogs. I peer through the grass and see him disappear behind the dyke. Doubled over, I take to my heels and run across the bare, open fields towards the Mokkenbank. I don’t know if I’m too early or too late, but I keep running, away from Meint, away from the frogs, away from deciding whether to go back.

The sandbars of the Mokkenbank lie grey in the advancing and receding waves. Overhead the gulls climb like whirling scraps of paper, hover in the wind and dive down. I clamber on to a fence and look around: not a soul in sight. Straining my eyes I scan the line of the distant sandbars; maybe he is there already, lying in the sun or taking a swim.

On the other side of the fence I stop to scrape the mud from my clogs. Isn’t he coming, or has he already been and gone? The sun is broken by the sea into dazzling splinters of light. I go and sit down at the foot of the dyke and shut my eyes tight against the glare. A cricket makes bright little chirping noises beside my ear, the sound becoming thinner and thinner, a wire vibrating in the sun.

I wake up when a pebble plops into the grass next to me. Walt is lying close by, looking at me. I feel dizzy. The earth is filled to overflowing with sounds, all nature seems to have sprung to life. Walt says nothing, he just whistles – I remember the tune – and turns over onto his back. I had thought the two of us would rush up to each other, that it would be like yesterday and he would be pleased to see me.

A little later we are walking through the marsh grass towards the sea. He carries me over a swampy patch, taking long strides and pressing on my burning arm. I am suspended in the air, without speech or will. Where is he taking me? Suddenly he stops, turns round and pushes me down roughly in the reeds. Two cyclists are riding along the dyke, I can hear the squeak of pedals and snatches of conversation in the distance. ‘Sssh. Don’t move,’ he says and pushes me further down. ‘Wait.’ He watches the approaching cyclists, his hand patting my knee reassuringly. ‘Kiss me.’

We stay there crouching for a moment longer, then he pulls me along to the beginning of the sandbar and goes and sits down in the cover of a circle of reeds. He holds me at arm’s length as if looking me over, brushes the hair from my forehead and tweaks my nose. He pulls off my clogs and draws me between his knees, pursing his lips to kiss me, a dry mouth against mine. He pulls his clothes up a little and puts my hand on his bare waist, a warm curve under my fingers.

‘You happy? You like?’ He has closed his eyes as he talks to me. I keep my hand nervously where he has put it, but his hand lies softly kneading between my legs. My body gives answer, I can feel it move under his touch and stretch out in lis hand, and I turn away to one side.

‘Jerome, come on.’ He speaks gently, as if whispering to me in his sleep, and pushes my mouth open. I let him do it, but remain tense under the squeezing and kneading of his hand. ‘Sleep,’ he says then, takes off his jacket and kisses the hillock in my trousers. Humming softly he lies down next to me; I listen: everything he does is beautiful and fascinates me. When I place my arm on his he looks at me in surprise.

The sand turns cold and wet under me, as if the sea were seeping into my clothes. He has stopped moving, his head has drooped to one side and his breath is heavy and deep. Above us the gulls complain and call.

I look into his defenceless face, the mouth that has fallen open slightly and the small white stripe between his eyelids. Every so often he makes a sound like a groan. He’ll take me away with him, I tell myself, if I don’t hear from home I’ll stay with him, he’ll wait for me in his car and then we’ll drive away to his country.

His cracked lips, the hollow sloping line of his cheeks, the eyebrows that almost join and his strong round neck, I pass them all in review, taking them in carefully, the colour, the outline, every irregularity, every feature: I must never forget any of them!

I slip my hand cautiously back under his shirt. He opens his eyes and looks at me in surprise, as if wondering how he has landed there, on this sandbar, with this boy and in this situation. He makes a chewing movement and swallows audibly.

I would like to say something, to talk to him; the long silences are oppressive and each time add to the distance between us. With a moan, he moves closer to me and I bury my face in his sandy hair. He folds his cold hands between our bodies.

Why does he keep falling asleep? I had thought he would do the same as yesterday; I was frightened of that, but now that he doesn’t I am disappointed. I think of Amsterdam: will I ever hear from them again, from my father and mother? What if they are dead, what will happen then?

I feel cold and tired; I ought to get up and go home or else I’II be late again, but Walt is sleeping peacefully, like a child. Now and then there is a rustle in the reeds as if someone were moving behind us and I lift my head quickly to look. The waves make startled sounds against the shore, over and over again the glittering water sucked into the sand.

Time passes, why doesn’t he move? A small beetle runs across his hair, trying laboriously to find a way through the glistening tangle. Then he is awake and scratches his neck.

‘Baby.’ He looks sleepily at me.

I am no baby, I am his friend. He looks at his watch, gets up with a start and pulls me to my feet.

‘Go,’ he says and gives me a gentle push. ‘Quick.’

It feels like being sent out of class at school. I slap the sand from my clothes and slip into my clogs.

He doesn’t remember, I think; he’s forgotten what we did yesterday. And he probably won’t be taking me away with him, everything is different from what I imagined. ‘What about tomorrow?’ I want to ask, but how?

He sits down by the edge of the sea and lights a cigarette. No kiss, no touch?

When I am standing on the dyke he is still sitting there just the same. I want to call out but a hoarse noise is all my voice will produce.

The rest of the day seems endless. In the afternoon we go down to the boat with Hait and help him bail water out of the hull. I do the monotonous job of emptying a tin mechanically over the side of the boat, filling the tin with a regular movement and listening to the dull splashes beside the boat, time after time, first Meint, then me, in endless repetition. Meint keeps talking to me while Hait gives us directions. I pretend to listen. They mustn’t notice anything. I mustn’t I give them the slightest inkling of suspicion, but must act as if nothing is happening. I speak, I eat, I move about, I bail water out of the boat, I answer Hait and make jokes with Meint, everything as usual…

But later, doggedly, I run a little way back up the dyke and scan the horizon. Clouds of white gulls rise brightly against the darkening grey sky: I can hear the far-off screeching very clearly.

I stare intently: that’s where he was, that’s where we lay…

‘Give us a hand, come on,’ says Diet and pushes’ the breadboard into my hand, ‘don’t just sit there daydreaming.’ The evening meal is over and I help her clear away. ‘You must have met a nice girl at the celebrations yesterday. I can tell by just looking at you.’ It sounds like an accusation.

I pretend to be indignant: me? In love?

‘Don’t try to deny it, it’s nothing to be ashamed of!’ She throws her arms around me aggressively, sticks her head out of the door and shouts with a laugh, ‘Hey, boys, Jeroen is courting, he’s going to take a Frisian wife!’

I find a big marble in the grass and walk back towards the harbour. The sun is low and deep red between long strips of cloud and the grey walls of the shack have taken on a pink glow, as if lit up by fire.

I go and sit beside the little grave among the stones. I push the marble into the sand, a beautiful one with green and orange spirals running through it. Over towards Amsterdam the horizon is a bright line. Will a letter ever come? How will I ever find my way back to them?

Chapter 6

The same house. It stands hidden between the trees at the end of the overgrown path. I recognise it at once: this is where we were.

The engine is turned off. The soldier gets out cautiously and walks towards the garden behind the small building, then disappears around the corner. A moment later he hurries back, his feet crunching on the gravel path. ‘Quick,’ he takes my hand and pulls me impatiently to the door. It feels pleasantly cool in the shade of the house after the hot car. I take a deep breath. The cry of a bird echoes clearly and challengingly among the trees.

Before putting the key in the lock the soldier listens out and looks back at the road a few times. We stand like thieves outside the deserted house. The turning of the key seems to break the spell, shattering the stillness.

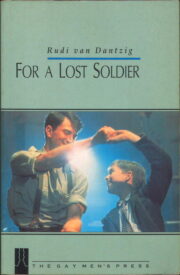

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.