‘You’ll have to ask Trientsje, the Americans gave it to her. She must decide.’

He moves his chair closer to mine at the table. Still I see the soldier, naked and large.

‘Ask, and it shall be given you, knock, and it shall be opened unto you,’ says Mem. ‘Asking, we’ve been doing that for a long time, haven’t we, Wabe? How often didn’t we ask God for an end to the war. And now it’s here!’ She drinks her tea with small, careful sips.

The finger moves from his prick to my mouth and rubs along my lips. I feel sick and swallow hard. ‘How did the minister put it again, that we have opened our hearts to our liberators, that they are guests in our souls?’

‘Be not forgetful to entertain strangers, for thereby some have entertained angels unaware,’ Meint says fervently.

I squeeze my legs together so as not to feel that movement between them any more, and tense my belly. I must think of something else. Hait looks at me. ‘And you, my boy, did you have a good day?’

I slide down from my chair, glad that I can move about freely, and go and stand beside him. He breaks Trientsje’s bar of chocolate into pieces and neatly wraps what is left into the silver paper. I make for the door.

‘I’m going to pee.’

The darkness outside descends upon me, an on-rolling ocean of muffled sounds; a voice calling in the distance, the short nocturnal cry of a lapwing.

The sheep are huddled against the wire fence in a grey clump, making human sounds, mumbling and coughing. In the distance are the small glowing spots of illuminated windows.

‘God,’ I say, and hope he can hear me, ‘let the soldier be my friend, let me always be with him. And don’t let anyone ever find out.’

I stand there, the cold spreading upwards from my feet. ‘I shall always go to church and always pray, I promise You. Please make him take me along with him.

I can hear a door opening in the house and a gust of speaking voices that wafts out and is quenched.

‘Jeroen?’ calls Trientsje.

I say nothing and crouch down in the dark. I put my hand inside my shirt and gently rub the sore place.

She takes a few steps outside and looks around the corner of the house, then steps into the cookhouse.

It hurts, I think, but it doesn’t matter if he stays my friend.

Suddenly I feel happy, he is probably lying in his tent right now thinking of me, or perhaps he’s at the table with the other soldiers, writing me a letter.

I feel the piece of paper in my pocket and clench it in my hand. Tomorrow he wants to go swimming with me, I shall be seeing him again, and I shall no longer be frightened. He is a liberator and he has chosen me, perhaps with God’s help. Thank You very much, God. With audible wing beats a silent shadow glides low across the meadow. I run to the ditch and look towards Warns. There is the bridge, there are the tents. I want very much to shout out into the dark over the still countryside, or to kneel in the grass, to do something.

When Mem calls me in an annoyed voice, I act surprised and innocent.

Shivering in the sudden warmth I get undressed and leap into bed before Meint has a chance to see my stained shirt and bruised arm.

I stare at the wall. His naked buttocks are so shamelessly close to my face that I hug them tight, a redeeming round shape that keeps me afloat…

The blood rises up inside me, beating in my throat and through my lips. Vaguely I hear Meint climb into bed and shut the little doors as quietly as he can.

Say nothing now, and don’t disturb my dreams…

Chapter 5

I hardly sleep that night. Every time I turn over I wake up with the pain in my arm, thinking of the soldier. A small shutter falls open in my head and I have a clear vision of all those things he did with me, as if it had all only just happened. Afterwards I can no longer close the shutter, I feel so guilty.

You must not kiss, kissing isn’t allowed, no one had ever kissed me, except at home, quickly and softly on the cheek. And there he had lain on top of me, naked, something that was completely forbidden. Suddenly I feel afraid: if I don’t go to meet him tomorrow, will he come here and take me prisoner?

My arm burns and my back is wet with sweat. I crawl over Meint to get out of bed and go to the privy. I pause at the back door; there are figures hiding everywhere in the dark, holding their breath, but I can sense their watchful presence as they lurk in the dark, waiting to pounce on me. I flee back to bed where Meint mumbles protestingly and turns over with a groan.

If you kiss a person, it means that you like him: Walt had held me tight in his arms, as if he wanted to squeeze the life out of me. Why did he do that, he didn’t even know me… I shut my eyes and try to sleep. Don’t think of ‘that’… Is it bad someone goes stiff down there? Diet says it’s a sin to talk about such things, but when it’s to do with an American it surely can’t be a sin; they only do what’s right and proper.

Just make the burning in my shoulder stop. He comes sneaking down on top of me and grins as he hisses at me to keep quiet, because no one must hear us. His hind legs are hairy and his tongue hangs pink and long from his snout. He is a dead cat…

I wake up with my head swimming. The mere thought of having to get up fills me with despair. Meint is already out of bed, yawning and stretching exaggeratedly, but curled up motionless I sullenly pretend to be fast asleep. I shall say I am sick so that they’ll let me lie in, life outside this bed seems bleak. There is nothing I want any longer.

In two minds I pull the blankets over my head; the hard patches on the bottom of my vest and the pains in my arm are problems I don’t want to face. But Mem flings the cupboard-bed doors open and whips the blankets off me. ‘Up you get, boy, this isn’t a holiday camp.’

Hait and Popke are still sitting at the table. It’s like a Sunday morning, everyone up late after the celebrations and still at home. Trientsje helps Mem clear the dishes and looks at my pale face.

‘Well, poppet,’ she says, ‘the celebrations are over now, so it should be back to work again. But the farmer’s going to have to do without me this morning. If all of you have been let off school, I don’t see why I can’t skip a morning as well.’

The water is ice-cold on my face and when Trientsje is not looking I push a wet hand inside my shirt and place it on my arm; it feels as if needles are being stuck into the wound. Mem is in a bad mood and sends all the children outside. She can’t seem to cope with the irregularity of this free morning. I have a slice of bread pushed into my hand, ‘Here, go and eat that outside.’

Hait strolls uneasily with Pieke along the fence, a free morning and no church! Meticulously he plucks tufts of sheep’s wool from the barbed wire and kneads them into a ball. I chew on my bread, my throat tight. There is the clattering noise of something falling inside the house, followed by raised voices. Jantsje rushes out sobbing and disappears into the barn. The celebrations are playing on all our nerves now.

I walk to the back of the house where the wind is less strong and fling my buttered bread across the ditch. The folded piece of paper lies in my trouser pocket, fingered so much that it feels as soft as a piece of cloth. I want to read it, I want to see those letters again, that secret message, and feel it between my fingers like a priceless possession.

Meint is crouching by the ditch parting the duckweed with a stick. The sun sends a shaft of light right to the bottom of the still, black water where a water-beetle is moving about amongst the weeds, its little legs furiously thrashing. ‘It eats tadpoles,’ Meint whispers, ‘we’ve got to kill it.’

I poke the water. The duckweed folds up over a small crimson creature that wriggles down towards the bottom in agitated circles.

‘We’ve got to find something to keep frogs in,’ says Meint, but I go off to the wooden privy without helping him.

‘Wednesday, 10 o’clock,’ and the thin lines with the letters L and W and the small cross showing where we are to meet. It looks like a capital T, the downstroke is the road from Warns to Laaxum and the cross-stroke must therefore be the dyke. Ten o’clock, how much time have I got left?

Meint bangs on the door. ‘Haven’t you finished your shit yet? I’m off to look for a tin at the harbour. Come on!’ Through a crack I can see the deserted, sunny road to Warns. I push my pants down, sit on the round hole in the plank and hope Meint will go off to the harbour by himself. I pick at the crusts on my stomach. My life is like a funnel that gets narrower and narrower, constricting me until I can’t escape. I tear up the piece of paper and let the snippets flutter down through the hole into the stinking pit below. Meint puts his face to the crack and makes spluttering noises with his tongue. ‘Shit-house,’ he laughs.

Crossly I go back into the house. ‘When is dinner?’

Mem laughs. ‘You’ve only just had your breakfast, we don’t keep going non-stop, you know.’

Down at the harbour I keep my distance from Meint, who is hunting about among stacks of crates on the other side. I must try to slip away unnoticed, which means hiding myself when he isn’t looking. My legs, dangling over the quay wall, are reflected in the water. The heat is oppressive and there is no one else in the harbour. Now and then the door of the shack bangs shut, breaking the silence like gunfire. Meint gives a shout and triumphantly holds up a tin can which he has fished out of the harbour with a stick. Thick blobs of sand drip out of it.

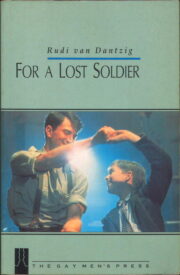

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.