Walt snatches the little card from my hand, pushes it back into the album and folds his letter up. As he touches my hand, I notice that my fingers have gone numb and are ice-cold, as if they are about to snap in two.

‘So?’ he says and adds a questioning, ‘Now what?’

He lies down and touches my knee. I can see the gentle curve of his back and the breath moving his stomach. I don’t have to be afraid, he is a nice man, anyone can see that. Gently, he pushes me over backwards.

Narbutus, Walter P., I think. I must remember that for later, then I can write to him.

He grips my hand and my heart throbs in my ears: everything has gone too still, why doesn’t he say something? When I swallow I have the feeling it can be heard all over the tent. I grope sideways with one arm and touch the cold barrel of the rifle. The fly buzzes up the slanting walls and I can see a patch of grassy field and the cloudless sky through the open tent-flap.

The soldier sits up and, reaching across me, tries to tuck the letter into a pocket in the side of the tent. As his body, leaning over, edges further forwards, I can see that his shorts have got stuck and that the naked spheres of his buttocks are emerging from the bunched-up material. I can touch them if I stretch out my hand.

He is lying there with a bare bottom, I think, his pants are coming off and he hasn’t even noticed.

When the letter has been put away in the side pocket, he lifts his body until he is arching over me like a bow and looks at me from under his arm. He gives his backside a few resounding slaps, takes my hand and repeats the action. The contact with the softly moving curves makes my hand begin to glow, a burning sensation as if his bare skin is contaminated with some mysterious substance.

He drops down and moves closer to me, propping his head up on his hand. Deliberately he unbuttons the top of my shirt, slipping his hand inside under my vest, until it meets the top of my pants. My heart beats wildly, I seem to be spinning over backwards, tumbling deeper and deeper. Don’t be frightened, nothing will happen: but my heart hammers furiously, ready to burst. ‘Okay, Jerome. No problem.’ He pulls his hand back. The hairy place in his armpit is close to my face. He uses his upper arm to wipe away a drop that is running down his ribs. Metal, the smell almost stupefies me. He places his lips on mine, I remember that from before and obediently open my mouth in the shape of a soundless scream. He is sucked fast to me and conducts a scrupulously close examination with his tongue. I dare not resist, he is bigger than I am, and stronger. He has a gun.

He speaks words I cannot understand, repeating the same sound over and over, and draws wet lines across my face with his tongue. Outside everything is still, the fly buzzes monotonously in the tent and further away someone whistles a tune. Walt fumbles clumsily with my clothes, pulls my vest out from under my belt and pushes it up. A button snaps off, making a tiny sound as it rolls to the side of the tent.

Suddenly he stops, lifts up his head and listens: voices are coming closer. What if they are people from the village, what if Hait and Mem missed me at church and have come here to look…

Walt crawls to the front of the tent and I breathe freely again. It’s over now and I’ll be able to go. But I am wrong: carefully he draws the tent-flap tight, shutting out the stretch of green field and the summer sky. On his knees he turns towards me and pushes his shorts down his legs.

What naked bodies I had seen up to now had always appeared in a flash, during embarrassed quick fumblings in the school changing room or at the swimming-baths. All I ever got to see were glimpses of lean, bony bodies, angular knees or part of a skinny ribcage hastily covered with a piece of clothing. Only Jan had been different, at the Cliff, a pale and fleeting memory.

The soldier kneeling over me is a collection of threatening shapes – shoulders, thighs, neck, ribs and arms – under which I lie imprisoned.

At night, on our street, we had sometimes talked about grown-ups, about what they do in bed. We would speak about it in excited whispers and then choke with laughter. Now this man is shoving my pants down, tugging at my vest and running his hands over me, touching me with his big fingers. My heart is like an overwound spring about to give one fatal bound and break. I push him away from me and try to say something, stumbling over my words. The raised-up body of this stranger is a grotesque reflection of all our whispered juvenile confidences, a feverish dream in which things swell to a monstrous size.

He spits into his palm – in a flash he has become a mirror image of Jan – and runs his hand between my legs. Then, warily, as if I might break, he starts to lie down on top of me, a building collapsing above me, a loosened rock about to crush me in its fall. He leans on his arms, his eye right above me, and gives me a reassuring smile. As he reaches down with one hand, he says, half-whispering: ‘Socio…’

I feel something – his hand? – making a smooth unchecked dive between my tightly squeezed legs. He slides down and in one short movement squeezes all my will power out of me. His arms seem to hold me in an embrace, but he is involved in a grim battle, snarling and straining convulsively as his breath comes fast and furious and his bristly hair brushes against my face.

When he raises himself up on his knees he looks past me as if I do not exist. Much as I once watched the hands of a doctor reaching for the gleaming instruments with which to snip the tonsils in my throat, so I watch his movements now. He spits large gobs into his hand, and then resumes that frantic activity of his. Why am I making no sound or protest, why am I not screaming out loud?

Suddenly he bites the top of my arm hard with knife-sharp teeth, and then I do give a twisted scream, tears burning in my eyes. The soldier has a red smear across his chin. Annoyed, he puts a hand over my mouth and makes a hissing sound.

His fingers smell of tobacco and iron. He is cutting off my breath and throttling me slowly, a great roaring pressure in my ears, a swelling-up of noise. Then he heaves himself up a little and something shoots across my body, running on salamander-like feet over my belly and my ribs in a thin line. As he collapses on top of me our bodies give a strange squelch, like a wet foot in the mud.

His voice is against my ear, whispering words: I can make out my name. A. hand travels groping down my belly: you have to pull, and to push… Embarrassed, I draw my legs up, I want to lie still like this, I don’t ever want to move again, ever see anybody again. He kisses me and looks at my arm. I feel no pain; I am shaken and drained, and dirty. The fluid between our bodies is turning cold and sticky. ‘Jerome, okay?’ Sweet and gentle. He pulls my vest down, there are damp patches on it. He wipes a cautious hand across my wet skin, pulls me up and puts my arms around his hips. I tremble, first in my hands and elbows, then all over my body. He pulls my pants up, fastens the buttons and buckles my belt, touching me all the time with his lips.

I crawl to the front of the tent. ‘Wait,’ he says, ‘tomorrow, swim.’ He picks up a piece of paper, writes something on it and puts his hands up, ten outspread fingers. ‘Tomorrow, yes?’ He is sitting with his legs apart, and with his finger he picks up a thin thread running from his sex to the sleeping bag and wipes it across my mouth. Then he kisses me. I shudder, the foulness of it all, all the things I was taught never to do… He pushes me towards the opening of the tent: ‘Go.’

The light outside is blinding: ditches, farms, the road. I can hear him coughing inside the tent. It’s as if I had never been inside: all over and done with, the cough just that of a stranger. I walk past the tents. Soldiers lying in the grass give me an unconcerned ‘Hello’. Do they know what happened inside the tent, do they think nothing of it?

I stand still on the bridge from where I can see the flags in the village: a great day. I look for his tent, the last one, a small green triangle in the field, peaceful and remote. No movement, no feelings, nothing, only the piece of paper in my hand. When I walk on, the wet patch on my shirt feels unpleasant against my skin. I pull my stomach in as far as I can.

Hait is sitting by the window, a shadow looking out into the colourless night. Now and then he rubs his foot and says under his breath, ‘My oh my oh my…’ It has a contented and reassuring sound. The family is safely back in its home again, the celebrations over for the day. We have been eating as if we were dying of hunger: white and rye bread, bacon, milk. Now we are waiting for the bar of chocolate that lies invitingly in the middle of the table, I keep seeing eyes straying towards it, but nobody will touch it and the mysterious object remains intact. My arm is burning; a small dark red stain has appeared on the sleeve of my shirt. Every so often I try to touch the spot and soothe the burning without being noticed.

‘That was a lovely celebration,’ Mem says, ‘and a lovely sermon, I haven’t heard the minister preach like that for a long time. And so many people, they were spilling out of the church.’

Pieke leans against my chair and rocks gently to and fro. Darkness is spreading without a sound and enveloping us.

Diet puts the enamel teapot on the table and hands mugs around, the steam from the pot rising in grey wisps.

‘Are we going to have a piece of chocolate now?’ asks Pieke.

The soldier crouches over me like a beast, threatening and watchful. Frightened, I look at Hait.

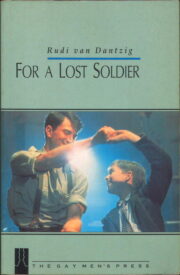

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.