‘Have you heard from home yet?’ I ask. I must remain friends with him, the two of us are going back together to Amsterdam. Jan spits into the palms of his hands and rubs them together vigorously.

‘No,’ he says, ‘but I don’t care, I’m staying on here anyway. I like it better here.’ There is a soft shadow on his sweaty upper lip and little white spots of sleepy dust in the corners of his eyes. He gestures with his head in Trientsje’s direction, gives me a knowing wink, and says, ‘She’s a bit of all right. Mind you squeeze her good and proper.’ He digs me in the ribs and runs across the road, right in front of the brass band. The noise thunders over us and overwhelms me. The musicians march past taking small shuffling steps, the sound they make rising up like a cloud of dust into the sky.

I can see Meint blowing his trumpet, red-faced, his eyes starting from their sockets. He keeps his gaze fixed rigidly on the sheet music clamped to the front of the trumpet, looking neither up nor down. My throat tightens at the sound of the music, I am being ground down between the mournfulness of the melody and the doleful counterpoint. A small open car follows behind the band with a soldier at the wheel and beside him another military man with a cap who brings his hand up to his head every so often in solemn salute. A tulip with a bright green leaf comes sailing out of the crowd, lands on the bonnet and lies there limply.

The car behind is full of soldiers hanging over the side and waving, some holding bunches of flowers in their hands. I look for a special face among them, but in a few seconds the procession has passed by. The people throng the road once more in the wake of the car and walk together towards the church.

I look around, but Trientsje has disappeared. Someone puts two arms around my neck from behind. ‘But if your father and mother come and fetch you, then I’ll go back with you,’ says Jan, continuing our interrupted conversation and pulling me back. ‘Remember, now, don’t you sneak off without me. Just tip me the wink, that’s what friends are for.’ He gives my shoulder a friendly push which sends me stumbling into a garden fence.

The brass band is lined up on the road in front of the church playing a solemn tune, the crowd joining in hesitatingly. Over their heads I can see the top of the army car. I walk towards the side where Hait and Mem are standing between villagers. Hait is singing. Mem looks impressive in her Sunday frock, a broad dark shadow engulfing Hait at her side. She listens with her chin raised, looking subdued and helpless, a little as if she badly wants to sneeze. Now and then she rubs her eyes awkwardly and nervously with a handkerchief. Hait could be her child, standing there beside her with a shy smile, his mouth moving as he sings.

When the song is over an engine starts up and the car with the soldiers drives off. The man in the cap has stayed behind; he walks up the church steps as if proudly showing off the gaudy stripes on his uniform jacket. In gleamingly polished shoes he goes up to the church doors, and stands there stiffly to attention.

As the car nudges a path through the crowd I try to get as close to it as I can. Isn’t that Walt, that soldier hanging on to a strut with upraised arms? Is he looking for someone or am I just imagining it? I use my arms to push through to the front, but the car is already too far away and gathering speed.

The church clock starts to chime and while everybody looks up, a gigantic flag is hung out from the tower. A hush descends over the houses: all that can be heard is the chiming of the bell and in the distance the drone of the car driving away through the village. I follow the crowd as far as the church doorway, then disappear as quickly as possible along the side of the little graveyard to the back of the Sunday school. A bit further on I find myself standing in the quiet street and without hesitating start running quickly across the bedecked road in the direction of the canal.

Walt is standing on the bridge as if he knew I was coming. He is hanging over the parapet and straightens up when he sees me, calm and relaxed, a lifebuoy to which I can swim.

‘Good morning,’ he says and kicks a pebble neatly into the water. He presses my head to his chest as if he were my father, then crouches down and lifts me up. ‘Hungry? Eat?’ We are walking to the field with the tents, his boots making a hollow sound over the water. Outside the biggest tent, several soldiers are sitting at a long table, listening to crackly music coming from a small radio. Walt sits down at one corner and pulls me down beside him.

‘Jerome,’ he says and turns me to face the men as if he were selling me. They mumble something and someone taps hard on the table with a spoon.

‘Eat,’ says Walt and pats his stomach.

I keep my eyes trained on the table-top and listen to the voices and the sound of the dinner things. Will the two soldiers from yesterday be there as well? Sun, music and the smell of hot food. I am handed a metal mess-tin and walk with Walt to the tent where somebody shovels a helping of crumbly, snow-white rice into it. ‘Enough?’

A young fellow with gleaming, freckled arms ladles a thick sauce with a sharp smell over the rice. I swallow and suddenly feel terribly hungry: American food, soldiers’ food, I really seem to belong here!

Staring into my tin, I start to spoon the food into my mouth, but I am so overwrought that I can’t taste anything, everything burns on my tongue and in my throat. Just so long as they don’t look at me. I can feel Walt’s knees against my leg under the table, pushing gently but insistently. The touch is electric. Carefully I edge my leg away from his.

Rice, chunks of meat, raisins, voices I do not understand and the sun shining in my eyes. My head swims. His leg is touching mine again, shaking gently as if it were laughing. Quickly I take a sip from a small mug Walt has pushed towards me and hold back a shiver. A soldier on the other side of me starts talking to me – slowly and emphatically. I try to listen to the patient voice steadily repeating the same words and short phrases as if I were at infant school, but all I am really taking in is the pushing knee demanding my attention.

I can still hear the bell in the distance. Now they are sitting in the church, I think, and feel a pang of regret. Am I going to be able to get away from here soon? With a shock I recognise the blond soldier who has come up and is standing next to Walt. They are reading something Walt has taken out of his pocket. Seeing the soldier’s hand on Walt’s shoulder makes me feel uneasy.

A bit later we are walking through the tents. Walt has placed a hand on my neck and is using the pressure of his fingers to steer me while he talks to the blond soldier. I am like a dog on a lead.

They stop by a small tent in which a man is lying down writing something. The blond soldier goes and sits beside him and unties his boots. ‘See you,’ he says. We walk to the last tent, at the very edge of the field. Suddenly I feel sorry that the other soldier is no longer with us. Walt seems lost in thought and says nothing. Swallows are darting over the grass and the sun feels warm on my back; from a long way behind us a monotonous voice is talking on the little radio.

Walt throws the tent flap open and crawls in. I crouch down: it is dim inside and smells of oil, like the sails of our boat.

‘My house,’ he says and rolls out a sleeping bag. I sit down on it when he points and see a rifle lying next to it. He takes a small book from a bag lying at the back of the tent and hands it to me. Photographs, some in colour, have been stuck in it behind transparent, shiny paper.

‘Me,’ he says, and points to a face staring tensely into the camera among a number of other boys’ faces. Can that skinny young boy really be the man sitting next to me? I bend over closer to get a better look.

The soldier puts an arm around my shoulder. I catch an immediate smell of metal. ‘School,’ he says and bends his head close to mine. ‘Me, school.’ I see the same boy at the edge of a swimming-pool and again with a dog on a lawn. Then suddenly I realise that the boy is obviously Walt. He is sitting on a floral settee beside a beautiful woman with a big, smiling mouth, their heads leaning affectionately together. I look carefully: who is she, this woman who is so obviously fond of him? His mother? She could just as easily be his sister or his fiancee. With her red lips and her blouse with its large open collar, this woman is smarter and more beautiful than our queen in the pictures I saw back in the village. Her hair falls neatly in glossy curls around her face.

I feel empty and disappointed: I look at all the people I do not know but who belong to him, who are his friends and more important to him than I am; the people in the photographs, and the two soldiers, too. I turn the pages automatically: Walt in a garden with the same dog – and even the dog bothers me – and with another boy, their arms slung amicably round each other’s shoulders. I turn the page quickly. Walt crawls across the tent, takes off his boots, sniffs at his socks and puts them outside on the grass.

When I close the book I realise that he has undressed. He is folding his clothes deliberately, wearing nothing but the shorts I saw him in on Sunday behind the sea wall. Opening a letter, he lies down next to me, scratches his knee and reads. I quickly open the album again and pretend to be looking at photographs.

A buzzing fly bumps along the tent wall, falling down from time to time on to the sleeping-bag. Time passes slowly, the letter rustles between his fingers and now and then he gives a long drawn-out yawn. A small card falls out of the album, a tiny photograph of Walt as he is now, with short hair and pinched, sunken cheeks, ‘Narbutus, Walter P.’ written under it in printed letters. So that’s what his name is.

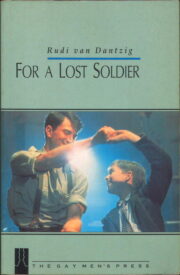

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.