He sits down beside me and puts a cigarette between my lips; by way of demonstration he takes in a deep breath, but the smoke has already reached my throat so that I splutter and cough.

He lies back again and blows smoke rings in the air that float away leaving a sweetish smell behind. The more I try to hold back my nervous coughing the more violent it grows, as if about to choke me. He takes my wrist and brings it hesitatingly to his face, watching my reactions intently. He blows smoke teasingly at me, his lower lip stuck far out, while I try convulsively to stifle a cough.

He bites softly into my fingertips and licks my palm; I clench my fist and he laughs. Then my hand is led to his throat, and I feel a swallowing sound transmitted to my fingers. He guides my hand across his chest, an uneven and mobile surface radiating warmth. Under the skin, where little hairs curl under my fingers like crawling insects, I feel a heavy, hidden heart-beat, a booming that tells me that I am not alone, another life, real and throbbing, next to my own. My hand travels across the small hills of his ribs, then over an even stretch, across a little hollow into which my fingers sink and where they remain: I am a blind man being helped from place to place, standing still, waiting, going back. The soldier is taking me on a guided tour of his body, inch by inch. I am his doll, a plaything with which he does as he pleases.

I look at the sky, a vivid blue flag over the circling gulls. Why is this happening to me, why has my life changed so suddenly, so utterly? I feel his stomach, smooth and flat. When he presses my hand down, there is scarcely any resistance. But when he inhales smoke, the surface hardens, remains taut for a few moments until he blows the smoke out again, when it all gives and goes soft again.

Bouncy little sand heaps, that’s what it feels like. In Amsterdam we used to jump on the pumped-out sand at the building site until the ground turned elastic under our feet and the water would come up. We would jump and jump until our shoes sank down in the mud. Then we would go home with wet socks: Mummy would be furious…

Unexpectedly my fingers encounter the edge of his pants, which he raises and pushes my hand inside. I pull my arm back and sit up straight. Silence. The soldier looks at me sideways. He fumbles with his pants and his fingers manoeuvre a floppy brown shape out through the flies, a curved defenceless thing. He lays his hand over it protectively, pulls me towards him and presses his mouth to my cheek. His voice is soft and soothing. What is he saying, what is going to happen now?

My ear grows warm and wet and a slopping sound seeps into my head, stupefying me. I pull my shoulders up and goose-pimples shoot in sudden shivers down my back and up my arms. He is licking the inside of my ears, I think, and they’re filthy, when did I last wash them? I am filled with shame, not because of the tongue licking my ear, but because of the yellow that sometimes comes out of my ears on to the towel and which he is probably touching with his tongue right now.

He lifts his hand from the thing and starts to turn it around slowly. It falls between his legs, then rolls across his stomach and comes to a standstill between the folds of khaki. As he rolls it around I can see it grow larger and stiffer. It seems to be stretching itself like a living creature, a snail slipping out of its shell. My dazed eyes are glued to this transformation, this silent, powerful expansion taking place so naturally and so easily.

‘When you grow up, you’ll get hair on your willy,’ the boys at school used to say. I had had a vision of some misshapen, hairy caterpillar, and I had hoped that they were wrong or else that I would never grow up.

The thing is now sticking up at a slant from the soldier’s body. There are no hairs growing on it, though I can see some tufts through his open pants. He makes a yawning sound, lazy and relaxed, as if the way he is lying there were the most natural thing in the world.

‘Is good, Jerome,’ he says, ‘no problem. Okay?’

The thing has a split eye which stares at me. I try not to look at it, but my own eyes seem riveted to that one spot. It is a clenched fist, large and coarse, raised at me. The soldier grasps it roughly and a drop of liquid seeps out from the split eye in the pink tip.

My own prick and Jan’s are small and thin, slender, fragile branches of our bodies. When the soldier lays my hand against his belly, the lurking thing suddenly springs up higher still, flushed out of its lair by the touch.

Under the rocks the sea surges to and fro, eddying and making gargling noises. Suddenly I can see my little room in Amsterdam quite clearly, the books placed in orderly array on the ledge of the fold-away bed, the framed prints on the wall and the place where I like to sit, under the window, out of sight from the neighbours. The sun falls across the rough surface of the coir mat where I have put a toy donkey out to grass. The voices of children can be heard outside playing by the canal. It is after school and I can smell food and feel the summer languor in my stomach.

It is far away, almost forgotten, a steady way of life that often seemed boring, a monotonous stringing together of days.

Mummy, I think, where are you?

The soldier presses himself closer to me. I can smell his nearness. Like a blanket, his smell spreads over me, protective and threatening all at once. His quick breathing unsettles me and he pants as if he were in full flight. But I am the one who should be running, running away…

I try to get to my feet, but the soldier suddenly uses force. We have become opponents, doughty and fierce. ‘Come on.’ He holds me firmly in his grip, his voice curt and impatient, squeezing my fingers more firmly around the knob and throwing his leg across me, the painful pressure of his knee pinning me to the rocks.

‘Let go of me!’ I shout the words out in a panic, and days later I can still hear their shaming sound. I know he can’t understand me, but the weight of his body grows less and his grip weakens. My arms are trembling.

‘Sorry, baby.’ He relaxes but goes on moving my hand up and down. What does he want, why does he make me do this, this horrible clutching?

I had heard stories about men who kill children; perhaps that’s how it happens, just like this. The thrusting inside my hand grows fiercer, he again bends over me and I turn my head away. On the rock beside me lies the stub of his burning cigarette; the smoke climbs up in a straight line and then tangles and disappears. When voices can suddenly be heard, clearly and close by, I pull my hand away like lightning, paralysed with fear. The soldier has already stood up, trying hastily to hide the awkward shape in his pants. Two unsteady steps and he is standing in the water. He falls forward and swims a few side strokes.

Two soldiers have climbed onto the sea wall, one of them whistling shrilly through his fingers and shouting. Walt turns round and stands up in the waves on strong, tensed legs, the sun casting luminous patches over his wet skin. The water barely reaches his knees. ‘Cold,’ he calls out.

He lets himself drop over backwards and swims off, sending up fountains of splashing water. One of the soldiers strips and wades in after him, the other one sits down a little to one side of me and lifts up his hand to me indifferently; he has bright blond hair and broad, round shoulders which he fingers constantly with obvious satisfaction.

I squeeze against the sea wall and hope that Walt will swim far out so that I can slip away unnoticed, but the two swimmers clamber onto the rocks nearby and then walk into the grass.

The blond soldier points to the small pile of Walt’s clothes, waits for me to pick it all up and then runs ahead, leaping from rock to rock. Close to the dyke we put the clothes down in the grass. Walt has slung a shirt over his shoulders and shakes himself dry. The blond soldier disappears behind the dyke and comes back with a crate of small bottles in a folded piece of oilcloth. He puts the crate down in the grass and whips the tops off a few of the bottles with a knife.

‘Coke?’ Walt passes me a bottle. The contents have a strong smell and at the first gulp a charge of bubbles fly up my nose.

With tears in my eyes, I hand the bottle back and shake my head: I am convinced I have been drinking beer.

In Amsterdam I once saw drunken Germans, with beer bottles in their hands.

‘Swine,’ my mother had said, ‘what a nation…’ and walking quickly had dragged me away.

The soldiers lie chatting on the opened-out oilcloth, smoking and rapidly emptying the bottles. Now and then Walt turns around and calls something out to me. Then he sings the song he hummed earlier and the two soldiers whistle along shrilly.

‘Jerome, sing. Come on.’ He walks across to me, pulls me up and does a few dance steps making me stumble over his feet. The others laugh. ‘Sing!’ He gives me an almost pleading look.

What am I to sing? Every song I ever knew has been wiped instantly clean from my memory. Walt holds my shoulders tight and seems to be trying to force it out of me.

‘Come,’ he says and squeezes me against his hard body,’sing.’

Confused, I look at the soldiers, what must they be thinking? One of them puts a finger to his lips and gives me a conspiratorial look. He steals closer and pours the contents of one of the bottles down Walt’s back.

Then, shouting, the two of them chase each other up and down the dyke. I don’t know if it’s in earnest but whenever they catch each other you can hear resounding slaps. I go and sit a bit higher up on the dyke to watch the fight from a safe distance.

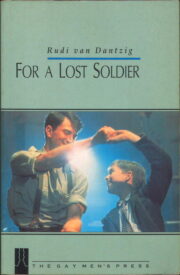

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.