Befuddled, I look into a small basin Mem is holding in front of me. A long thread of slobber is hanging from my mouth and stinging morsels burn in my throat. Mem pats me patiently on the back.

When I try to clutch Mem’s hand so as to have somebody to hold on to, she has already gone. I can hear her clogs in the lane and a dragging sound as if she is moving something, or somebody. Who? I sit up.

But perhaps it’s just the wind…

In the evening, Trientsje softly opens the cupboard-bed doors. ‘Aren’t you sleeping?’

I can see the others in the room having a cold meal, hear the clicking of knives, distant voices, and I see Hait nod to me. Mem feeds me porridge, her hand rises insistently each time to my mouth, and dutifully I accept the spoon. Afterwards, I feel better, the warmth settling like a cossetting wrap around my body. Content and babylike I let Mem get on with the business of wiping my face and neck with a wet cloth and then she tucks me in firmly under the blankets.

‘He’s on the mend, his temperature is down,’ she reports to the room.

Could I ask them for my coat? I want to smell the sleeves and have the soldier near me. I must know what he smelled like again…

When I feel somebody beside me I sit bolt upright, in a panic.

‘I shan’t eat you, you fool,’ Meint chuckles.

In the dark I listen to the creaking of the floorboards and feel him tugging at the blankets.

‘Can you get anything you like from that soldier? Even chocolate?’

I pretend to be asleep and say nothing. If only I had my coat with me, I long for his smell. I turn to the wall and try to recapture his face, the slope of his cheek, the broken tooth.

Meint is asleep, I can hear him breathing gently and regularly.

Did I get sick because I had somebody else’s spit in my mouth, is that dangerous? Then I remember with a shock that he had wanted to take me for another drive today. My body grows hot and wet: will he be cross with me, did he wait for me? I can feel small drops on my forehead and my heart is beating fast.

The soldier crouches on the rails behind the small barn. He looks at me, holding me prisoner with his eyes.

Chapter 3

Because she thinks I am still sick, Mem tells me not to go to church next morning. The dirty breakfast things stand on the table in chaotic confusion. The living-room is deserted.

I step outside and watch Hait, who is walking down the road to Warns with the children. It is glorious spring weather, the girls’ coats are unbuttoned and Popke and Meint are gaily sporting white shirts. An army car comes towards the small group of church-goers, hooting loudly as it passes them, tearing a hole in the Sunday morning stillness.

The car turns off on to the sea dyke, stops a bit further on and a few soldiers get out and walk along the dyke. They look around before disappearing out of sight down the other side. I stroll back indoors and look through the window: the car looks lost on the road, like a motionless decoy, frozen in silence. I am in two minds whether to go up to it or stay at home. Mem is sure to find it suspicious if I’m suddenly well enough to go to the harbour.

I take a few faltering steps. ‘I’m just off to the boat, to see if everything’s all right.’ Obediently I put on my coat. ‘Else you’ll get sick again,’ Mem calls after me.

There’s not a soul at the harbour. A white goat is grazing at the end of a rope and gives a piercing bleat as I pass. The boats’ masts rock lazily to and fro, gleaming like knitting needles. The quay is deserted. I kick a stone into the water: placidly ebbing circles. Should I go back? My longing for the safety of my cupboard-bed into which I can creep and shut out the world becomes stronger with every step I take: the darkness and the seclusion, and the caring hands of Mem bringing food and straightening the blankets.

I walk to the other side of the little harbour. Seagulls flying over the sea wall retreat when they see me, still gobbling helplessly struggling fish in their hooked beaks.

Further along the dyke sheep are grazing. From a long way off I can hear the regular sound of their grinding jaws tearing out the grass.

Silence and wind, not a living soul, no soldier, nothing. A metal drum makes ticking noises as if the heat were blasting the rust off it in flakes. I walk up to it under the nets hung out on poles and lay my hand against the hot surface. A hollow sound. I look at the reddish brown powder that has stuck to my hand and smell it. Iron.

I am vaguely reminded of the smell of the soldier; how is it that I can remember the smell of his touch? On the pier which protects the little harbour from the sea I walk alongside the beams of the weathered sea wall, placing my feet carefully on the rocks, afraid to lose my balance. In the shelter of the timber boarding the heat is suddenly overwhelming. I sit down, my head swimming.

A broken beam gives me an unexpected view of the sea, a greenish-grey surface moving restlessly and filled with light. The wind blows straight into my face and when I open my mouth wide to catch the current of air it is as if the inside of my head is being blown clean, and the last remnants of my lingering sickness are swept away.

The turbulence of the water washes away my lethargy. I stick my head through the opening between the beams and look out over the wide, empty expanse of the coastline. On the distant rocks the vivid, irregular shape of a human figure intrudes upon the splendour of the view, a man lying on his back in the sun, a completely isolated, insulated being.

I quickly turn my head away as if my mere look could disturb the perfect stillness and privacy of that distant man. My gaze settles on the quiet tedium of the harbour boats bobbing against the quay and roofs dipping away behind the dyke. But the sunbathing figure behind the sea wall draws me like a magnet, pulling me with invisible threads that tremble with tautness as if they were about to snap.

Without hesitation I climb over the fencing and am suddenly quite alone at the mercy of the hurrying waves and the solitary sunbather. Holding tight to the beams, I balance across the stones towards him. Every so often, the water splashes up between the rocks and makes white patches of foam in the bright air.

The sunbather has heard me and turns towards me, calling out something cut short by the wind: it is my soldier. He lies stretched out on a rock and smiles at me with his eyes screwed up. When I am quite close, he sticks out his hand. I take it and immediately let go of it again. ‘Hello, good morning.’

Best walk on calmly now, as if I had to be getting on, as if I were on my way to somewhere else. But his hand clasps my ankle so that I can’t move. ‘No, no. Where you go?’ He tugs at my leg and pulls me closer. He is wearing nothing but khaki shorts. ‘Sit,’ he says, ‘sit down.’

He moves up to make room for me and then stretches out in the sun again. His arms are folded lazily under his head and he surveys me with an almost mocking look. The front of his shorts gapes open a bit, confronting me with a part of his body I am not supposed to see. Embarrassed, I turn my head away and look out across the sea as if something in the distance were suddenly attracting my attention. Even his hairy armpits, exposed so nonchalantly, make me feel that I should not be looking: there is something not quite right, something that doesn’t fit.

The soldier pulls me down next to him on the rock. Now and then I throw a quick glance at his half-naked body in the hope that his flies will have closed again. ‘Jerome,’ I hear him say. ‘Sun. Is nice, is good.’

He yawns, stretches and slaps himself on the chest with the flat of his hand, hollow, resounding slaps. I feel relieved when he sits up. His legs dangle down from the rocks and his feet have disappeared in the water. His back is a smooth, unblemished curve with a pronounced hollow down the middle. The unevenness of the rock has left white impressions on his skin and some sand and pieces of dirt have stuck to his shoulders. He makes splashing sounds with a foot in the water, but every so often, as if to take me by surprise, he turns his head towards me; trapped, I quickly avert my gaze. From out of the corner of my eye, I see him get down and stand in the water, one hand on his hip and whistling a tune between his teeth. A jet squirts straight and hard from his body into the water making a frothing patch of little bubbles and foam in the waves. Before he sits down again, he walks up to the fencing and looks over it, searchingly.

The water has a salty tang. A small white fish drifts about between the rocks, staring up with a dull, sunken eye as it continually collides with the dark volcanic rock. Casually the soldier taps a slow rhythm out on his thighs. Spread over the edge of the rock, his upper body moves about jerkily, and he hums softly to himself. Above us two gulls hover on motionless, outstretched wings, their heads turned inquisitively towards us as they keep us under close scrutiny.

Suddenly he stretches his arms and makes flying movements, uttering screeching noises in the direction of the birds. I make an attempt to laugh. The gulls slip away, but keep their heads turned suspiciously towards us. The soldier stands up, then squats down by a small pile of clothes and lights a cigarette. I lay my hands on his trail of wet footprints on the rocks. It suddenly seems important to me to do this and I want to memorise the contact: the foot of a liberator I have touched, have felt with my fingers.

The soldier leans against the sea wall, puffing hard at his cigarette and smiling at me. From further away he seems less overwhelming, the feeling of oppression he gives me and the memory of what he did with me have begun to fade.

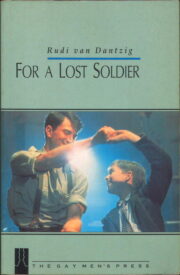

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.