Voices sound from the house, footsteps pass over the gravel, for a moment I am free and catch my breath as if coming up from deep water. Then he pushes me against the wall by my shoulders and tilts his head to listen. Nearby an engine starts, but the sound moves away from us and disappears.

Gently he wipes away a thread of spittle running down my chin, as if to console me. I am standing in the mud in my socks looking for a clog. Everything feels grubby to me, wet and filthy.

‘Jerome,’ he asks, ‘Jerome, okay?’

It happens all over again, the mouth, the hands, his taste which penetrates me, which I can’t shake off, and the rough lunges that suddenly turn gentle. I feel cold, my face is burning and hurts; from my throat comes a strange, strangled sound. I am afraid that if he lets go of me I shall fall down and will never be able to get up again, that I shall die here in the mud and the rain, forgotten behind an old barn.

He puts an arm around my waist and pushes me quickly through the wet shrubs alongside the barn. His car starts silently and quickly. A little further along the road he stops and pulls me to him. I start to cry, softly at first then harder and harder, my shoulder-blades, back, arms, knees, everything shaking and trembling.

Why is he smiling, how can he be so friendly and act so ordinarily? Why didn’t he do what I thought he was sure to do, leave me behind trampled flat in the mud?

He takes out the map and opens it, his finger follows a red line and then points to a dark spot: he is looking for a lonely place to throw me out at the side of the road.

‘House?’ I hear him ask, ‘Jerome house?’ I bend down over the spread-out map, which rustles on my unsteady knees.

‘Jerome, look.’

When I start to cry again, he holds me against him and lifts the map up in front of my face.

‘Warns,’ I read beside the small dot where his finger is. I point to Laaxum, printed there clearly in small letters. Is he taking me home, do they have to see me step out of an American car?

He kisses my eyes dry and to my horror licks away the threads running from my nose with a mouth that is coaxing and soft and cleans me lovingly.

We drive on again, the soldier stroking my back continuously. I no longer cry.

‘Say Walt, say it,’ he begs, ‘Jerome, come on, say Walt.’

In surprise I listen to my voice reacting hoarsely as it is asked. I feel an overwhelming urge to lie down on the seat, but stay sitting up, looking straight ahead with smarting eyes: I must know where we are. He takes my hand and places it on his leg where it remains limp and lifeless. The rain has stopped. His taste is in my mouth and refuses to go away. Will it stay with me for the rest of my life, this sense of being immersed, of being steeped in filth and fingers? I sag sideways on the seat while the soldier lights a cigarette.

He lets me out at almost the same place I got in. Awkwardly I remain standing beside the car as if waiting for something more, a sign or a command to disappear. He raises a hand and winks, then the door swings shut and I take to my heels without looking back. I race through the village, along the edge of the road, my head hunched between my shoulders so that no one can see my face. But the street is quiet, it is raining and there is no one about.

I can’t go home, that much is certain, I have to be alone and think what to do. Beyond the village I crawl down the side of a ditch, to the bottom where the ground is wet and the chill penetrates my clothes. I can feel his taste in my mouth, in my throat and on my tongue, a bitter smell clinging to me, a mixture of metal and hospital odours. When I sniff at my sleeve, the smell of the soldier is so strong and immediate that he might be sitting right next to me. I taste my spit, let it travel down my throat, dividing it with my tongue and gathering it together again. I want it to go away, I must be rid of it. I spit and it drips in a long stream into the grass.

Mem will know straight away what has happened to me, she’ll be able to read it in me as if it were written in large letters all over my body. I am sure that my eyes are bloodshot and swollen, and my face feels battered, grazed and smarting.

Without thinking any more I take the turning to Scharl and trudge towards the isolated farmsteads in the distance, pushing against the strengthening wind. Muddy pools sometimes cover the entire road, reflecting the yellow-white streaks that now and then break through the black clouds. A gust of wind blows a pair of screaming birds across my path. I keep an eye on Jan’s farm, wondering whether I should go over there and see him. He is the only person I can tell, but perhaps he, too, will just tease me and then go and tell everybody else. I stand still, in two minds. If he talks about it, then I’ll be utterly lost. Quickly I walk past his house and hope that no one has seen me. I must remain invisible, unnoticed.

A moment later, there is a downpour. I run past the dark slope of the Cliff and clamber across the dyke. The sea is a grey, tumultuous mass into which the torrential rain is drumming small punched holes. Near Laaxum, where the sea wall begins, I huddle close to the piles and sense the water under me, hurricanes of furious spray, foaming as it streams between the blocks of basalt. I run my fingers over my face. Everything appears askew, pulled apart. Can I present myself at home like this? I do not move and slowly start to stiffen.

At home they are still at table, a closed circle under the oil lamp. Faces look at me, all except Meint who continues to eat, bent over his plate.

‘Where on earth did you get to, why are you so late?’

I have no answer.

‘Don’t just stand there, take off your coat.’ Mem pushes her chair back and looks appalled. ‘You’re making everything wet.’

‘School. I had to stay behind at school, do some drawings.’ With a shock I realise that I have left the precious box behind in the car. Now everything is bound to come out.

Hait takes me by the shoulder and ushers me out of the room. ‘We must have a bit of a chat, my boy.’

So that’s it, he knows everything already, I won’t be able to hide anything. Leaning against the wall, I strip off my wet clothes and pretend to be busily occupied.

‘Is it true, Jeroen, what Jantsje tells me?’

I try to look surprised and innocent. ‘What?’

‘Jantsje says a soldier gave you sweets, the boys from the village saw it all.’

Relief leaps up in my throat, I bow my head and nod.

‘If you’re given something, you mustn’t keep it to yourself, surely you know that? It isn’t very nice to keep things for yourself.’

I look into his thin face, a tired man trying to look severe. I am not his child but a guest, a refugee from the city. He stands awkwardly facing me in the dim little room and almost smiles at me. I want to go and stand next to him, I want him to hold me close. Dispassionately, I lay the little packet in his hand. ‘One of them is gone. I’m very sorry, Hait.’ Now I’m crying all the same.

Hait tears the blue and red paper open and holds the four thin silver slabs in his hand. My secret, my precious secret… ‘Four. One for each of you. Go and hand them out.’ He steers me gently back into the room. I lay one slab each next to Meint’s, Jantsje’s and Pieke’s plates, that’s how Hait would want it. But the fourth, is that for me? I put it down beside Trientsje but she pushes it back gently. ‘Keep it for yourself.’ I leave it on the table for them to decide who gets it, Diet or Popke. In any case I’m rid of it, I don’t need it any more. It came from the soldier and he has to be banished from my memory. I sit down at my place, but don’t eat. ‘Don’t you want anything? Are you sick?’ Please don’t let them ask me any more questions, please make them leave me in peace. I listen to the others cleaning their plates, the smell of the food and the heat making me dizzy.

When I swallow I can taste the soldier, strong and sickly. I must eat something, I think, then it will go away, then I’ll be rid of it. But suddenly, inexorably, I know that I don’t want it to go.

In the morning, Mem comes to look at me. She places a large searching hand on my forehead and says, ‘Much too hot. You’d better stay in bed for the day.’

Behind the closed doors of the cupboard-bed, waking and dozing off again, I am aware of scraps of the day passing by: distorted voices float up from breakfast, and a penetrating smell of tea gives my stomach cramps from thirst.

As I clasp Mem’s hand and take greedy gulps from the mug she holds to my mouth, I notice that the soldier’s taste has vanished, dissolved in my sleep, gone. I keep swallowing.

One dream later, the soldier is pressing me against the wall, his tongue an eel that creeps into my ears, into my nostrils, into my throat. The soldier reaches out for me, grinning and winking. I can feel the eel wriggling around my feet and then slithering up my legs. When I pull away, the soldier jumps into the car with a soundless scream and drives wildly after me. Behind the car rushes a bloodthirsty, furious mob led by the minister’s wife. I hide beside the sea and they all fall into the water, one by one…

Then I hear the sound of peeled potatoes plopping into a bucket. The cupboard-bed is unimaginably large. I lie like a dwarf between the blankets, the narrow walls miles away.

‘Mem?’ Am I making a sound or am I merely moving my mouth? Tea, I’m thirsty, I want to say, but I can’t talk, I have no voice. Eternities later, I look into Mem’s anxious face.

‘What’s up with you, what are you talking about? Coloured pencils, we don’t have any of those here, you must have had I those in Amsterdam.’ She pulls the blankets up. ‘Just you lie quietly now and try to get some sleep.’ Her hand is stroking me gently. Or is it him, suddenly back?… the soldier pushes chewing-gum into my mouth, a gag that grows thicker and thicker. He shoves it down until it’s stuck in my throat and I can’t draw breath any longer. I fight grimly to free myself and thrash about wildly…

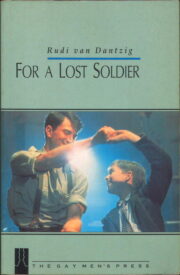

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.