Using exaggerated flourishes, he writes the words on two separate blackboards and our two classes, joined into one for the occasion, dedicatedly copy his ornamental letters into our exercise books.

William of Nassau, I,

a prince of German blood…

one of the anthems begins. How can we sing that now: ‘a prince of German blood’? Shouldn’t we be going and wiping out all the Germans, now that the war is over? I had taken it for granted that we would all be marching straight into Germany with pitchforks, sticks and rifles to give them a really good hiding in their own rotten country.

‘Anyone finished copying may go home, there are no more classes today. The school will remain closed for a few days, until after the celebrations. Off you go and enjoy yourselves.’

It is drizzling, and we hang about undecided in the school porch. Should we go back home or shall we make for the bridge? We walk, awkwardly because of the strange time of day, through the village street, hugging the house fronts for shelter.

A moment later Jantsje catches up with us, panting, her exercise book with the anthems pressed protectively to her chest. ‘Jeroen, the master wants you, you’ve got to go back.’ She is looking at me gleefully, has it got something to do with that packet of chewing-gum? I never told anybody at home about it, but this morning as we filed into school Jantsje suddenly whispered to me in passing, ‘I know what you’ve got!’

I feel in my pocket where the packet is tucked away, warm and pliable. They won’t be getting any, it’s just for me and no one else is going to touch it, I’ll make sure of that! I run back to school, walk down the stone passage and stop when I hear voices. I can see the master in the classroom with two men I know vaguely by sight. They live in a part of the village we seldom visit and they are standing stiffly and awkwardly beside the blackboard.

I walk up to the master’s table, wondering what it is this time, what they can want with me. ‘This is one of the pupils from Amsterdam,’ he says. ‘Shake hands with the gentlemen, boy.’

Silently I put out my hand, my eyes riveted to the tabletop. Am I about to get news from home?

The master’s voice sounds friendlier than usual and I listen in amazement. He says that the visitors are members of the festival committee for the liberation celebrations and that they are looking for a pupil who can draw nicely.

From his desk he brings out a drawing I once made of a wintry scene, a farmer pulling a cow along by a rope. ‘You didn’t know I’d kept it, did you now?’

The men bend over the drawing and then look at me. Do they like what I’ve done? You can’t tell from their faces.

‘You will understand, of course, why we thought of you. The drawings have to be about Friesland, a fishing boat or something to do with our dairy products. And a national costume never comes amiss either. We shall have the drawings copied on a larger scale and then hang them up in the Sunday school.’

‘It would be very nice if they were in colour,’ says one of the men in a drawling voice, ‘that’s always more cheerful. After all, it’s for the celebrations. And that’s why we also thought of putting these words underneath.’ He fetches a piece of paper from out of his pocket on which we thank you and underneath V = victory are written in big capital letters in English.

I can’t believe it: they need me, they want me to do something for the liberation celebrations! Everyone will look at the drawings and know that it was me who did them…

‘I’ll do my best. When do they have to be ready?’ I am back in the porch, a box of coloured pencils they have given me in my hand. The school yard is deserted, the drizzle has turned to rain. The houses across the road are reflected in the smooth pavement.

The emptiness of the yard seems to increase the solemnity of the moment: there I stand all alone on the steps with my newly commissioned assignment, ready for a fresh, unknown start. Yesterday that present from the soldier and now this. My luck has changed!

A green car drives through the deserted street, the tyres making a lapping sound over the rain-washed stones. A piece of canvas hanging loose and blowing like a flapping wing in the wind looks like a ghostly apparition, lending the village street, in which I have never seen any other car since our arrival from Amsterdam, a completely different appearance. The houses seem smaller and the road, with the car in it, looks suddenly narrow and cramped.

Like a messenger from the Heavenly Hosts, of whom I have heard so much about in church, the vehicle whirrs past me, an imposing, combative angel. I slip into my clogs and start to run after it. At the crossroads the car stops and a soldier leans out. He calls. I stop and look behind me, but there is no one there. Surely he can’t be calling me!

‘Hey, you!’ He leans out of the window and waves to me. I look up into an intently inquisitive face. It is the soldier who gave me the packet of chewing-gum yesterday, the same chapped lips, the same searching eyes.

He opens his mouth as if he wants to say something and then realises that there is no point. Perhaps I ought to say something, but what? ‘Thank you’, or ‘V = Victory’, the English words the master wrote in my exercise book? But I don’t know how to pronounce them, even if I were brave enough to try.

The soldier looks inside the car for a moment and then holds another red and blue packet with a silvery sheen up above my head. ‘Yesterday,’ he smiles suddenly with a friendly grin that makes all my heaviness of heart fall away. He is like a divine apparition enthroned above me against the grey, massed clouds, as he raises the little packet up to heaven in what might be a gesture of blessing. Small beads of drizzle glisten in his hair, and a thin gold chain gleams under his throat, moving gently as if he were swallowing his words. It is in strange contrast to his strong hairy arms and unshaven chin. His face is like something I had forgotten and am seeing again after a painfully long time. It is almost with gratitude that I recognise the tooth with the chipped corner and the sharp groove setting off his mouth. The door opens; a leg jerks nervously and impatiently, as if there is a hurry. ‘Hello, come on in.’ I understand because he pats the seat beside him invitingly and nods his head. Should I really get in, can I refuse to? I ought to be getting back home, so I can’t really… He whistles impatiently and spreads his arms out in a questioning gesture. Before I know what has happened, he has leaned out and seized me by my coat. Reluctantly, I step onto the running-board and allow myself to be pulled into the seat, where I edge as far away from him as possible. Why am I so frightened, he has a friendly face and won’t do me any harm. On the contrary: with a few determined movements he beats the rain off my coat and puts an arm around my shoulder.

‘Hello,’ I hear again. I try to say the same thing back, hoarsely and timidly. They are right, I’m a scaredy-cat, too frightened to say boo to a goose. I clutch the box of coloured pencils as if my life depends on it and look at the door.

‘Okay.’ He stretches across me and slams the door shut. ‘Drive?’ he asks. ‘You like?’ His hand goes to my thigh and gives my leg a reassuring pat.

The car judders and then we are away. I hold tight to the seat, and whenever I see people I make myself as small as possible, no one in the village must see me sitting in a car belonging to the Americans.

While we are driving he looks at me, his face half turned towards me and his eyes veering from me to the road and back again. Why is he watching me like that, doesn’t he trust me?

We have left the village behind and are driving towards Bakhuizen, on a road I do not know. I have never walked here and the unknown surroundings frighten me as the familiar ground disappears from under my feet.

In the middle of an open stretch he slows down and then stops the car by the side of the road: that’s it then, now I’ll be able to get out and hare back to Laaxum. But the soldier lights a cigarette, leans peacefully to one side, and gazes across the rain-drenched land and at the shiny wet road. Carefully, I move my hand to the door handle and try to turn it without his noticing: I can barely budge it. The soldier takes my hand from the handle with a smile and continues to hold it.

‘Walt,’ he says pointing to himself. ‘Me, Walt. You?’ and digs a finger in my coat. I quickly free my hand and mumble my name under my breath, ‘Jeroen.’ I am ashamed of my voice.

‘Jerome?’ He puts out his hand and pinches mine as if trying to convince me of something. ‘Okay! Jerome, Walt: friends. Good!’ His lips make exaggerated movements as they form the words he utters with such conviction.

It is as if his hand has taken complete possession of me. I feel the touch run through my entire body. He has narrow fingers with bulging knuckles, the clipped nails have black rims. His thumb makes brief movements over the back of my hand in time with the windscreen wiper.

We are moving again, he gestures around the cab and gives me a questioning look. ‘Is good, Jerome, you like?’

I nod, and I’m beginning to feel a little bit easier. When the road makes a sharp curve, I lurch sideways and fall against the soldier. He puts an arm around me and stretches out the word ‘okaaaaay’ for as long as it takes to go round the bend.

We pass houses that seem to be bowing under the downpour and bedraggled trees that appear more and more often until they have grown into a wood. Everything slides past me through a veil of rain, whisked away from the windscreen with resolute flicks of the wiper. The arm around me feels warm and comfortable, as if I were enfolded in an armchair. I let it all happen, almost complacently. This is liberation, I think, that’s how it should be, different from the other days. This is a celebration.

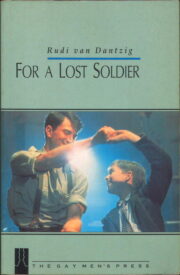

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.