There is nothing at the crossroads any longer. The junction of the three roads looks bright and still in the morning sun and it feels almost like a Sunday. I walk past the school, where is everybody? At the bridge, I find the answer: gathered there is the largest crowd I have ever seen, with the possible exception of the funeral of the minister’s wife. I work my way forward through the people and look for Jantsje and Meint. Shoving against backs and wriggling past dirty overalls I suddenly see the bridge, the bridge that is no longer there.

Torn in half, the two ends are hanging in the water, a shocking and pathetic picture of violence in this slow, quiet landscape. Snapped-off railings, planks broken in two and twisted struts overturned in the water, it seems beyond repair, destroyed once and for all. I look at it in dismay. The bridge is like a great animal, blown to pieces and crumpling as it dies. It will never be put right again, suddenly I know it, it can never be rebuilt. I have an immediate foreboding that the war may never come to an end.

I push in among the other children standing close together at the edge of the water, silent and dejected. Uncertainly, I stop still, afraid to move any further; my elation has made way for panic.

There is Meint, right in front. But where has Jantsje got to? I have to take them back home, they must be dragged out of here quickly, back to Laaxum, back to the stillness by the sea.

‘Have you seen the Americans? Over there, that’s them!’ A village boy pulls me forward and points, ‘Our liberators, now we’re free!’ He waves across to the other side and then cries out with a sob, ‘Long live Wilhelmina!’

A few green trucks have been parked on the other side of the canal and soldiers are walking about among them. There are also some odd-looking open cars, small and innocent like toys. Disappointed, I look at the peaceful scene, a scene that seems so unconnected with war, a handful of soldiers moving about calmly, almost lethargically, between the cars, carrying poles and piling moss-coloured bags onto the grass. They don’t appear to be giving us a thought, but just go about their business imperturbably, looking neither left nor right.

Armies as far as the horizon is what I had thought the word liberation meant, masses of soldiers carrying heavy guns, rifles and banners to the blare of bugles; an incalculable host of julibant, heroic fighters, muddy, tired and dirty, but still singing triumphant songs. The entry of heroes…

Two men get out of one of the trucks and begin to put up tents. One of them, who is stripped to the waist, walks to the edge of the water and waves: the first liberator to look at us! An awkward arm goes up stiffly here and there in answer to his greeting, but only the children cheer out loud and respond to the wave with exuberant leaps and yells.

‘Come on,’ I say, ‘we’ve got to get back, Mem is worried, she doesn’t want us to hang about here. It might still be dangerous.’

‘Just as well, I’m hungry,’ Meint says matter-of-factly. ‘Don’t those Americans eat? Where do they do their cooking?’

That question occupies us for most of our homeward journey: what and where do the soldiers eat, and where do they come from? ‘Americans come from England as well, of course,’ I maintain, because I have always been told that we would be liberated by the English. My father had always listened in secret to the English radio, so these men simply had to be English, and that was that.

‘Do they have to live in those little tents?’ Jantsje asks, and, ‘Will they be coming to liberate Laaxum as well?’

‘Liberate us? What from?’ asks Hait, shifting about impatiently at the table. ‘No one has ever set foot in Laaxum, they don’t even know it exists.’ He looks at us cheerfully. ‘Everything stays here the way it always has been, and just as well too.’

We are sitting side by side on the quay wall, captivated by the mysterious darkness of the water beneath us. A fish darts through a strip of sunlight, a brightly glittering star thrown off course. I follow the twisting movements, the almost complete halt and the flashing away at lightning speed, but my thoughts are on tomorrow, on the bridge, the soldiers and the fact that what is happening there is the liberation.

Mem had forbidden us to go back to the village: ‘There’s nothing for you there, it’s grown-ups’ business.’ It seems incredible that, half an hour away, something so important should be going on while we are hanging about the harbour dangling our legs with nothing to do.

Jantsje lifts her head, looks across the sea and points vaguely at the horizon. ‘Perhaps the Americans have crossed over already, and your mother and father are being liberated as well.’ I make no reply and stare at a school of minnows slipping from boat to boat. Carefully I work a small pebble to the edge of the quay and suddenly let it fly in their direction. There is a violent rush, as scores of fish vanish as one like magic in the shadow of a boat.

I had wanted to ask Hait a lot of questions over lunch, but for a long time I had been afraid of talking about home and the war, a fear that had eventually turned into glum resignation. The answers they gave me were always evasive: ‘How long will the war go on?’ ‘Young ’un, we have no idea.’ ‘Is there any food left in Amsterdam?’ ‘Let’s just hope so, and don’t you pay any heed to what people are saying, they know no more than we do. One day they’ll come to fetch you, after all they brought you here.’ ‘When?’ ‘It depends on the war, and who knows how long that’s going on for?’

No letters and no news from home, for months now, only those vague non-committal evasions which were absolutely worthless and merely added to my confusion. This morning, when I had watched the soldiers across the canal, I had felt my courage ebb away: how could that handful of men possibly liberate all of us, they would never make it…

The school of minnows slips back along the hull of the boat and the little fish start to sip with small, fastidious mouths. Pieke, who keeps hobbling up and down along the quay wall, kicks my hand as I search for another pebble to throw. Whimpering, she cries that she wants to see the Americans, that she is always being left out and that she wants to go to the village right now.

Meint has clambered into the boat, and, getting down on his knees, begins teasingly to throw small sticks from the deck in our direction. ‘Why don’t you ask Mem,’ he mocks, ‘she’s sure to let you.’

Then, unexpectedly, Jantsje takes her little sister under her wing and says she’ll borrow a bicycle and take Pieke along to Warns. I go on sitting where I am, suddenly feeling sleepy and worn out, just wanting to curl up in the warm sun and to think of nothing at all. Still, it might be a good idea to go and look up Jan, he might not have heard anything yet about the soldiers by the canal.

I remember how the boys in Amsterdam always said to each other, ‘Just you wait, when the English get here they’ll finish Jerry off in no time.’ And now our liberators have turned out to be American, and not English at all! While I’m Still feeling just a little triumphant, I’ll go over to Jan’s and tell him what’s happened, Jan, who always knows everything. He won’t know what’s hit him this time though!

But I am afraid to go to Scharl. Imagine if the woman there says that Jan left some time ago, that he’s gone back home and hadn’t told me. I would be all on my own then, deserted, betrayed. Whenever Jan doesn’t turn up at school for a little while the thought creeps over me, dimly at first and then more and more insistently until the shattering truth dawns: Jan has gone, I am all alone… Then I can think of nothing else, my longing for Jan assumes frightening proportions, and I am given over, heart and soul, to homesickness.

‘Hey,’ says Jantsje, bicycling over the dyke with Pieke on the luggage carrier, ‘we’re off, Jeroen.’

‘Wait for me.’ I slip into my clogs and run up the path. Jantsje has already bicycled away and I run after the girls at a jog-trot.

A miracle has happened by the blown-up bridge. A narrow gangway of brand new planks is in place across the water. Three soldiers are working on it, hanging down over the canal, sawing and knocking in nails with loud, determined hammer blows. Behind the army trucks small green tents have sprung up right across the fields, and a kind of storage depot has risen next to the largest of them, with boxes and tins and a mountain of kit bags half-covered with a tarpaulin.

Close by, on a bench, a few men are having a relaxed conversation, so relaxed one might think they were enjoying a Saturday afternoon chat in their front garden. And a bit further on, to our amazement, a couple of them are swimming in the canal, laughing and shouting like small boys, disappearing under the surface, now and then sticking their legs up to the sky and spitting water out of their mouths in small arcs when they come up for air. Large swathes have been cut through the duckweed, showing where the swimmers have been.

One of them climbs out on to the bank, hoisting himself up between the reeds, and as he stands up I realise with a shock what Jantsje is saying out aloud – ‘See that, it looks as if he’s got nothing on at all.’ Suddenly silent and sullen, the girls turn their heads away and I, too, take a startled step backwards. I can’t tell if the soldier is actually naked, but it’s a strange enough sight anyway to see grown men being so playful and high-spirited, trying to push one another into the water, giving each other bear hugs, wrestling and kicking out at one another with loud yells, tearing exultantly through the water like young animals, as if neither war nor liberation meant anything.

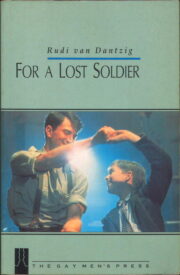

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.