I allow it to happen again and again, I examine it time after time. When I start out of my sleep at night, it is looming up ominously at the back of my vague dreams: I have it, too, and it is bad, it is a sin.

A dark, rainy afternoon. I had felt completely superfluous in the little house, imprisoned, caught in a trap. There had been no post for weeks, a fact that had burned a hole of uncertainty inside me. And though Hait had explained that the post in Holland was no longer working because everything had been closed down on account of the war, I had secretly kept looking put of the window every morning to see if anyone was bicycling up from Warns to bring us our post.

It was also pointless for me to write to Amsterdam, Mem had said, because no letters were arriving there either, a waste of paper and stamps. But I kept writing all the same, secretly.

I would take the envelopes from the small chest of drawers but I had no money to buy stamps. So I would drop the letters in the post box without stamps, having written the address in big fat writing across the envelope, on both sides, hoping that might help. Or else that my prayer might help, the one I uttered as the letter disappeared from my fingers into the dark slot: God, make them get it, please. If only You wish it, Thy will be done.

For a long time I obstinately stuck to the ritual of writing, putting letters in the box, and waiting hopefully for a reply.

That rainy afternoon I was convinced that a letter would be coming from Amsterdam: on the way to school I had seen three herons standing by the ditch, and that meant good luck, and the Bible passages we were told to read in class seemed to contain a hidden message too: despair not, salvation is nigh! In the village a farmer’s boy whistled a tune that resembled a song my mother always sang, I had recognised it with a start. That too was a hint, a sign meant for me alone.

But there was no letter. I searched everywhere in the room for that small white rectangle that had to be waiting for me on the chest of drawers, or on the mantelpiece. There was none, and I was too scared to ask Mem.

But something simply had to come. I couldn’t be left waiting and hoping and guessing like this for ever, surely they must realise at home that I was pining for some sign of life? What were they up to, then? Suddenly I rushed out of the house, telling Mem that I had forgotten something, that I had to go back to school.

On the road to Warns I turned off to the left and took the muddy side-road to Scharl, to Jan. The farmsteads looked gloomy in the bleak landscape, there were still a few lone sheep, but most of the stock had been taken from the meadows to spend the winter months in warm stables. All activity seemed reduced to the wind bending the trees and a wet dog yelping piercingly to be let in. I walked hurriedly, my eyes fixed on the path. I did nothing to avoid the pools of mud, but waded grimly through them, stamping my clogs into the water with wild delight and feeling the mud splash up my legs.

They had simply forgotten me, that’s what it was, that’s why there were no letters, they were glad to be rid of me. Now they could have a good time alone with my little brother, that was what they had wanted all along of course. I drowned the idea that something terrible, something irrevocable, might have happened to them under a wave of self-pity and baseless reproaches. But deep down I knew how unreasonable I was being and that there was nothing anybody could do about it: not my parents, not the people in Laaxum, not anybody. It was just the Jerries and the lousy war. But I was stuck with it, and that was that.

A farm labourer hurried across the road, squelching through yellow-brown puddles of manure, his boots sucked firmly down into the sludgy morass. ‘Weather’s a right shit!’ he shouted in my direction. ‘Not fit for dogs! Why don’t you get out of the rain?’

The land and the farmyards seemed to have turned into a swampy quagmire in a matter of days. I could feel rain-water seeping into my clogs and running down my face. I would it lick away, together with the snot from my nose. I was drowning in the dismal melancholy that came dripping out of the sky, drenching everything and everybody.

The family with whom Jan lived were busy in the stables, dragging buckets and noisy milk churns about. A small oil lamp was burning on the wall, and a little greyish light came through a low, arched window. The farmer himself was half-hidden under a cow, his cheek pressed against her loins as he grabbed at the pale pink udders, monstrously bloated with veins fatly swollen as if they were about to burst. I looked at his hands squeezing the cow’s dangling teats roughly and uncaringly. A white jet shot through his pumping fingers and frothed into the bucket.

‘Have you come to see Jan?’ The woman was suddenly standing behind me and I turned round, as if caught in the act. ‘He’s inside. Go and look in the house.’

The house lay to one side of the stables. I walked through a garden where red cabbage and leeks stood among a tangle of plants gone to seed. I spotted Jan through one of the windows. He was sitting at a table with his back towards me, his legs stretched out on a chair. I put my hand against the glass and peered inside. I was spying on a completely different way of life, one in which everything seemed matter-of-fact and calm, where a boy could stare into the fire glowing peacefully in the stove. I wondered if he was asleep.

Oh Jan, mysterious, strong Jan whom I wanted to see so desperately, for whom I longed. There he sat so close to me, almost within reach, but even now, a yard away from me, he seemed unattainable, many lives removed from me. Did I have the right to bother him with my tearful despair? Could I disturb his private, dark tranquillity?

I wanted to turn round and make off before I was seen. The window-pane rattled when I withdrew my hand and the boy in the room turned his head in surprise, squinting in my direction. I raised my hand and pulled a face. To my relief, I saw Jan’s face light up in a pleased smile.

The room swam in black shadows, the furniture floating on a deathly still, dark sea. In a corner an oil lamp made spluttering noises and from the stable adjoining the room came the subdued lowing of a cow, tormented and in pain. Occasionally there was a clanking like heavy chains being beaten together, and it seemed that Jan, motionless, was listening out for that sound.

Feeling my way with my feet I stepped into the dark room and moved towards the chair. ‘Don’t you have to work today? I thought you always helped?’

‘No, I’m not allowed to do anything for a few days.’ When Jan got up from the table I could see that he had a bad limp. His face was pale and his reddened eyes, strained and weary, had a troubled expression. His initial pleasure at seeing me seemed to have vanished. He made his way awkwardly across the room, overturned a cup on the windowsill with a clatter and looked out of the dark window.

I had wanted to look the place over, to see how he lived, what sort of things were part of his daily life, but I was afraid to. As if rooted to the spot I remained standing in the middle of the room and kept my eyes timidly on the sullen figure by the window.

‘Come on, let’s go upstairs, I’ll show you my den. Or would you rather stay here?’ He opened a door at the back and walked in front of me up a steep little flight of wooden stairs. The stable sounds were very close now through the plank wall and there was a sweetish scent of hay. Excitedly, I followed him up the blue-painted stairs. I was being admitted to the room in which my hero slept, where he dreamed, a world of mysterious deeds I had only been able to guess at in my imagination. It was sure to be a place of unlimited promise, of friendship, shared secrets, of silent touches and discreet meaningful glances.

The little room was small, more a partitioned corner of the attic, with almost the same dimensions as my cupboard-bed. Even so, I thought, it’s his own room. Here he can read, lie on his bed, here he can be alone. He doesn’t have to share anything with anybody.

Jan pointed to a small window which did not look outside but gave onto the hayloft. You could see the haystack, dug into on one side, and beyond it a corner of the pigsty. A heavy wooden beam ran in front of the window, covered with thick layers of grey cobwebs to which dark pieces of dead insects were attached, and the planks beyond were covered with a grotesque layer of bird shit.

‘Shall I show you what I’ve done?’ Jan tried to pull up a leg of his overalls but the material caught in a lump around his knee. Annoyed, he sat down on his bed and began to undo the top of his overalls, his finger tugging impatiently at the buttons.

This little room is like a nest in a tree, I thought, suspended between dark branches and protected by cobwebs. Even I bough you couldn’t look out you could feel it was getting late, you could hear the darkness closing in on us, caressing our limbs. In the gloom of the room I could see a pale torso emerging one shoulder at a time from out of the overalls and hanging there luminously, fragile and tender.

I felt myself grow hot with excitement: this was a hidden place that no one knew about. What was about to happen here was something I would discuss with no one else, a silent, wordless happening between Jan and me. I had the feeling that I was about to discover the real Jan, that he would strip off the layers of indifference before my very eyes, revealing at long last who he really was. I heard him get to his feet and saw him push the overalls down. What was he really up to, what did he mean to do? Was he going to do again what he had done at the Cliff, the bare belly and the sticking-up thing?

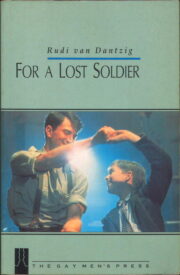

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.