Already, I think, I want to go back already… Never been out to sea, what sort of a man am I? Gasping for breath I try to talk unconcernedly to Hait, but he pushes me out of the rear seat with a firm hand. ‘Go and sit in the middle and hold on tight. And look out for that sail up there!’

He shouts the last few words, pushing me down forcefully at the same time. With a deafening clatter and the creaking of ropes the boom slams over our heads. The boat almost ships water. Meint, who is standing opposite me, is suddenly high above me, a moment later sinking steeply into the depths with a gigantic swoop. It is as if a pump in my stomach were squeezing the contents down with all its might. Don’t think about it, it is sure to pass, this is fun, this is an adventure… I mustn’t be sick, or they will laugh at me. But I struggle for air and feel the pressure under my throat grow stronger.

I cling to the dripping edge of the boat and work my way towards the middle. There I sink safely to the bottom, my back against the side, my feet against the crate in which the catch is stored. The sheep is falling from one side of the deck to the other, floundering about on blundering legs. Meint calls to me and laughs into the wind with forced heartiness. I admire him, he moves with quick agility across the slippery deck and his spirits are high. Gamely he staggers towards the sheep and ties the rope tighter and shorter. The sheep does not bleat, falling patiently backwards and forwards, but I can see the panic in its unseeing, staring eyes. I try to outshout my own fear and call something back. I can hear my voice bawling and sounding false. I laugh noisily and feel cowardly and insincere.

So this is what sailing is like, having a good time at sea and not being at school. My body is ice-cold and my fingers are numb. A strongly rising wave of nausea and the realisation that I am powerless to do anything to stop it makes my jaws begin to chatter uncontrollably. Desperately, I clench my teeth. Don’t vomit, not now…

And we used to sing about sailing at school, ‘Sailor, sailor, we’ll go with thee-ee, out to sea-ea, out to sea…’

Popke kneels down beside me and points to the shore. With effort, reluctantly, I get up on my haunches and see something on the shoreline that looks like a small hill. I give him a questioning look. ‘The Red Cliff,’ Popke shouts in my ear, ‘don’t you recognise it?’ Another wave of water sweeps over me, making me duck. Was that miserable, paltry little hillock the Cliff where Jan and I played? Was that the happy, warm, green hill that you could see rising so majestically above the land from our house? The sails again catch the wind with the sharp crack of a detonation.

Meint comes leaping towards me and leans overboard by my side, staring into the water. Hait, too, bends over, looks, cuts down the engine, and beckons to me. I hear a weird scraping and scouring noise, as if an animal were scrabbling and gnawing at the bottom of the boat. We are making almost no headway, but are pitching crazily up and down. The engine sends up impotent little puffs of smoke that make me feel sick, filling my nose and throat with a bitter taste. The thudding under the boat grows more insistent. When I get up and lean overboard my knees feel limp and weak.

Right next to me I can make out two gigantic rubber shapes sticking up out of the waves like ghostly apparitions. I can touch them if I put my hand out. ‘The aeroplane,’ Meint shouts excitedly into the wind, ‘can you feel it, we’ve sailed right on top of it!’

He slaps the heavy rubber tyres with a smacking noise, once, twice, and then he can’t reach them any longer. Eyes open wide, I stare at the terrifying objects, phantoms from another, mysterious, world. Beneath me there are men hanging upside down. I feel I know them, that they are familiar beings, drowned friends. So close by, surrounded by fish and seaweed, hanging, swaying, in filmy, heaving veils of water. Their arms move forwards, reaching out, beckoning: a swirling dance of death.

A moment later the contents of my stomach gush out into the waves, in a broad, yellowish stream.

When we reach Stavoren Hait says sympathetically that I needn’t go back in the boat if I don’t want to: I can walk back, it isn’t all that far to Laaxum. But an hour later, with timorous resignation, I allow myself to be hauled back on board, go and lie down in a corner under some sails and hope for the best. Think of it: anything could have happened on the walk back. I could have lost my way, or something else might have gone wrong, then I could have said goodbye to my new home as well.

In Stavoren I had immediately spotted the three German soldiers. They were standing about in the middle of the quay, and though they didn’t stop anyone their look was alert and keen, as if they were trying to see through your clothes. Their presence brought Amsterdam and the war startlingly closer again. The grim threat of shining boots, drab green uniforms and voices that sounded cold and hard was something I had almost forgotten here in Friesland, but suddenly it all came back again, that haunted feeling of suspicion and fear and of things that had to be done on the quiet, unseen.

I had made myself as inconspicuous as possible at the harbour, and had in no way betrayed the fact that I was seasick. If the Jerries had noticed that I was no fisherman but a boy from Amsterdam, they might have picked me up straight away. I had the feeling that they had been waiting for me there in the harbour. Maybe they had found my registration card and knew my name and number and had been looking for me all this time…

The return trip passed amazingly quickly. I lay dozing under the canvas, half sick, being tossed about in an unresisting heap. Before I knew it, the wind dropped, a benign calm descended over the boat and all the tightness ebbed out of my stomach. The sound of the engine grew faint and the sails came rustling down. I crept out from under the canvas and felt the warm air caress my face. Close by, craggy and familiar, lay the quay wall. I stepped onto it – the hero returned from his first sea voyage – and felt the ground sway under my feet: the land, too, seemed to have turned to water. No doubt that’s what they call ‘sealegs’.

A fisherman came striding along, his clogs sounding hollow on the stone path: it was music, dear, familiar music!

Back to Mem now, back quickly to the house standing firm and foursquare in the meadow, to sit down once more at a table that does not move!

An hour later I am sitting in front of the house, a late, fading sun casting pale patches of light across the fields. I have a hymn book on my lap and am trying to learn a psalm by heart for Sunday school tomorrow.

All the time I have been here, all these weeks and months, all these Saturday evenings, I have hit on no better way of getting these incomprehensible passages into my head than reading the stupid verses methodically over and over again until they stick in my memory.

…My soul cleaveth unto the dust: quicken thou me according to thy word. I have declared my ways, and thou heardest me: teach me thy statutes. Make me to understand the way of thy precepts…

Far away, almost directly opposite our house, hidden among clumps of trees, I can make out the roof of the farmhouse where Jan lives. In my mind’s eye I see the spacious, empty farmyard, now muddy and rain-washed, the tall stable doors, the living room with the kicked-off clogs outside the door. Jan is there, my saviour, the friend with whom I am going to escape. Does he sometimes look over this way as well, does he ever think of me?

I have already worked out the plan: one Sunday afternoon I’ll skip church and go and meet Jan by the harbour. I’ll have been able to take some food from home because they’ll all be at the service. We’ll make good our escape, and we’ll have a headstart of several hours before they start to miss us. Jan said we could sail across in a boat, but I’ll talk him out of that idea. I’ll never go out to sea again. Much better to make for the big dam, once we’re over that…

‘…You have declared my ways…’

Wrong.

‘…I have declared your ways…’

Wrong again.

‘…I have declared my ways, and thou teachest me…’

Dammit.

White rage wells up inside me, I’d like to smash the book against the wall or tear the barbed wire on the fence apart with my bare hands. Stinking, putrid life…

All the unfairness, all the uncertainty, all my sickness and fear, all the incomprehensible and unbearable longings, everything I yearn for that is unfulfilled… Lousy, stinking mess.

‘…My soul cleaveth unto the dust: quicken thou me…’

Jan, if only you were here, pushing my arms into the grass again or putting your hands around my throat; anything is better than this, this nothingness, this emptiness, this hopelessness.

‘…And thou heardest me: teach me thy statutes. Make me to understand the way of thy precepts.’

Chapter 10

Three days ago it happened to me for the first time. In bed at night, the only place and moment in the day when I can think about home, quietly and undisturbed, I turn to the wall and draw lines from me to Amsterdam, channels of communication between them and me. But the last few nights I have been thinking of Jan all the time. I try to push him away, but he stubbornly forces himself upon me, manipulating my thoughts like a tyrant, whether I want it or not. What bothers me most is that I do want it, that I am happy to give in to my fantasies. I touch my body, with shame and caution, as if someone were watching me.

This is me, this is my chest, my belly, these are my legs and the warmth I give off is mine. And the small, unseasoned twiglet that grows and stands up under my touch, the thing that seems anchored in my insides by deep roots, is that mine as well, do I have any influence over that swelling and that shuddering bulge?

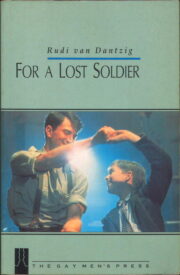

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.