The minister looks straight at us, to our surprise. He even gives a brief nod in our direction and smiles. I cannot conceive of Mem changing back into the usual loudly chattering, bustling housewife in our overcrowded little living room. I fully expect this death to have turned her, too, into a silent, motionless figure for good.

The children wait outside until the cortege is in the church, then we go in last and sit down at the very back. The church is so full that we can see almost nothing of what is happening at the front. ‘She’s next to the pulpit,’ says Popke, ‘there’s going to be a service first.’ I want to look for Hait and Mem, but am too ashamed to be seen peering around the church while she is lying there dead: what would she think of me?

When everyone stands up as the minister walks in, I look up tensely at the pulpit, unable to imagine what the minister is going to do next. What do you say when your wife has died? But a different minister gets up in the pulpit, a strange, ordinary-looking man who makes nervous gestures with jerky, disjointed waves of his arm. He keeps sipping water from a glass standing ready next to him. At one point he starts to cough convulsively, barking like a dog, and afterwards he looks out into the body of the church in consternation, as if thinking, What on earth was I saying just now?

I am disappointed, no, furious: what is this man doing in our minister’s place? Does he imagine he can take over his job, or that any of us are going to believe anything he might tell us? I watch him carefully. It looks as if his Bible is about to fall off the pulpit, and he can’t even preach. The lifeless, listless mumbling carries no further than the front pews.

Although I have never actually spoken to our minister, I have the feeling that we know each other well and that many things he says in church on a Sunday are meant, not for the whole village, but for me alone, to console me or to give me courage or simply to let me know that he understands me.

I would sometimes glow with pride and excitement when he looked in my direction during a sermon: you see, he’s making sure I’m there! During the hymns I often looked straight up at him to let him see that I was singing along at the top of my voice. I thought that the minister, just like myself, felt a bit of an outsider in the village, a duck out of water. Townish people are treated differently, they don’t really belong.

Sometimes I indulge in fantasies. I see myself rising suddenly out of my pew as the organ starts to play by itself, and all the swallows come flying in through the windows. Then I float up high in the church on beams of golden light, my arms spread wide. I am wearing flimsy white clothes that flutter in the wind and there are voices raised in songs of praise. I am drifting on these voices. They lift me up while the swallows circle about in glittering formation. Everyone in the church looks up in awe as I hover there between heaven and earth, and some people fall on their knees and stretch out their arms towards me. ‘That boy from the city, the one who’s staying with Wabe Visser – he isn’t just an ordinary boy, he is someone special in God’s eyes.’ The singing becomes louder and louder and I call down to them that they have no need to be afraid, that everything will turn out for the best. Filled with impatience I await the day when all these things will come to pass. Sometimes I feel that it is near at hand, and there I’ll be, up on high. But something always intervenes. No doubt some arrangements still have to be made. And when the time comes I shall first of all do something for my parents, and for Jan. But also for Hait and Mem, and for the minister’s wife. And the minister. That’s quite a lot of people. I have only to ask and things will change, will get better. God will see to that.

We never saw our minister again after the funeral. For a while we were saddled with that clumsy interloper, and Sundays become an affliction. I made the journeys to Warns with bad grace and on the way back home I would tear to pieces everything that we had been assailed with from the pulpit, every last why and wherefore.

Then another minister came, a long-winded, boring old man. Religion lost all its appeal, and there was no longer any question of floating on high in the church.

A small black and white object is drifting in the waves under a cloudy, threatening sky. Sometimes I can see it clearly, occasionally disappearing until I spot it again a bit further away, bobbing up and down in the swell. Armed with a stick I crouch on the shingle and wait patiently for the tide to bring it in.

It is a kitten, its bulging belly floating on the water like a balloon, its limbs and head drooping down. I try to fish it towards me, thrashing about in the sea with my stick. It must be rescued from the cold water, it must be taken to safety, it must not be allowed to go on endlessly rolling about in the water. Finally it is in reach and I lay it down at the water’s edge, a crumpled coat, limp little paws and a grinning vacant face. I go to look for a piece of wood to carry it to the small beach on the other side of the harbour.

Just beneath the shingle I dig a hole in the wet sand and place the kitten there on a little bed of grass. Miserably wrinkled and creased, it lies on its side, a pitiful little toy. I pray as the minister might have done, using his words and intonations.

When the hole has been filled in again, I go back home to fetch a small paper flower Mem keeps in a drawer, and place it on the grave. On this spot, unknown to anybody, I can hold acts of worship. From here I can send up my prayers for my mother and for the minister’s wife. I can make offerings: pieces of broken pottery, a peeled-off ten-cent postage stamp, the lid of an old slate pencil box. If I am kind to the kitten, my prayers are sure to be heard. That’s the way it is. For a time, it absorbs my attention so much that even my memories of Jan and the afternoon on the Red Cliff become blurred.

Chapter 9

In the morning when I look out of the window with sleepy eyes I can see that the cloud cover is beginning to break up in the distance. For days the sky has been covered with low, dark clouds, like a lid on top of a pan. I had been feeling dejected and listless: the daily journey to school had suddenly seemed an insurmountable obstacle course to us, and the house, so crammed with people and their doings, had felt too small and threatening as if everything had been conspiring to drive me into a corner and curb my freedom.

‘Now we’ve had it,’ Mem had said, stamping her clogs in the stone yard, ‘winter is coming.’

The land lies chill and washed clean under a leaden weight, pools of rainwater sparkling in the grass and the cows moving through the sodden pasture on hooves black with mud.

When we were getting up, Hait had said to me, ‘Today we’re going to take a sheep to Stavoren, in the boat. It looks as if it’s going to be a fine day, so if you want to come along, just tell Mem. You can skip school just this once.’

Besides, it’s Saturday, and if I do go along I won’t be missing anything that matters. Saturday mornings at school seem to be nothing more than preparation for the doldrums of our Sunday rest.

I try to keep my balance as I walk up the wobbly gangplank to the boat where, tied to the rail, the sheep already lies meekly waiting, panting heavily.

It is still quiet in the harbour, a few fishermen are busying themselves with buckets and flat wooden crates, their voices echoing along the quay. A bucket of water, emptied beside a boat, has the tumultuous sound of a plunging waterfall. Though I have been on the boat several times, I have never gone out to sea in it. Either the boat had already left, or I would be missing school, ‘And your parents wouldn’t want that,’ Hait would say teasingly. There was always something to keep me on land. I didn’t really mind, except that Meint kept teasing me with, ‘Never been out? You’ve honestly never been out to sea? Ha, what sort of a man are you?’

All four of us sit down in the protective shell of the clog-shaped boat as, making little plopping sounds, it slips out of the harbour. The water behind us is split open into gently undulating lines that grow wider and fainter the further away they get. Hait is at the tiller, hunched up and looking unexpectedly small, while Popke and Meint are busily engaged with a tangle of ropes and canvas.

I look out from the little seat at the back and note how, all of a sudden, it is possible to take in the village with a single glance and how, faster and faster, first the small houses and then the quay wall, the workshed and then the pier, are being sucked away from us.

Once out at sea, the boat starts to pitch in the waves. My stomach chums. I grip the edge of the boat tight and feel the first splash of water, slap, in my face. The quay wall is far away by now, too far away…

When we swing around towards Stavoren, Popke and Meint hoist the sails. They look like large brown wings filled by unruly powers, time and again catching the wind with violent smacks. The boat lists suddenly and I topple over, to be caught by the sure arm of Hait who looks on calmly from the tiller as we draw a swirling curve of foam through the water.

Shrieking gulls dive behind us, emerging from the surf with fish in their beaks. The harbour has become a tiny doll’s harbour. Small and brown – a stripe, no more – the wooden sea wall follows us up the coast for a while. The large basalt blocks protruding from the water look like toy building blocks, paltry playthings scattered along the coast. The boat rears up more violently and the sea flings yet more waves of ice-cold water over us. I catch my breath and with chilled fingers cling convulsively to the edge. When Hait looks at me I smile back politely, a petrified smile. My boat trip is an excursion into a world of violence, of thrust and counter-thrust, a fight with chilly, flapping demons who are consigning us to the depths of the sea with explosive salvos of laughter. I look back with longing at the safe land.

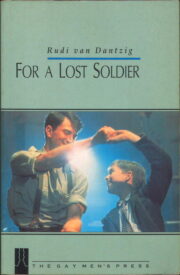

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.