‘Come on!’ I wave my arms and start leaping about like a madman. ‘Hey, hey, hey!’

He comes slowly up to the top, balancing with bare, outstretched arms. His body slanting forward and his head looking down, he takes huge steps.

‘Gosh, you’re so brown already.’

Jan wipes drops of sweat from his nose and lifts his arms into the air. Brown, scratched arms. He looks out over the yellow-green landscape, which he seems to be keeping at bay with a movement of his arm, like a general. He hitches up his sagging trousers and takes stock of the slope. ‘Let’s roll down.’ He gives me a playful shove. We had rolled down once before, but I had finished up at the bottom retching into the sea while the whole world seemed to spin in large circles around me.

I go and lie down at the edge of the slope. ‘Ready, steady… We’ll see who wins.’ I no longer care if it makes me sick, so long as we are together, so long as Jan plays with me.

‘Hang on, we’ll do it doubled, like this.’ He lies down on top of me and puts his arms around me. I can smell his acrid sweat. ‘Ready?’ He laughs and without any warning squeezes the breath out of me. Over we roll, slowly and lopsidedly, then faster and faster. Over and over I see Jan’s face against the blue sky and then against the dark grass. Our bodies bump into each other and I hear Jan catching his breath with excited laughter. I shut my eyes tight and cling to him as we drop like a stone into an unfathomable deep.

Stop, I think to myself, stop! and then we are lying still. Grass rustles and grey circles spin around in my head. I break into a sweat, feeling Jan’s body pressing stiflingly and stickily against me. He pants heavily into my ear. ‘Jesus,’ he sighs, ‘sweet Jesus.’ Are we never going to move again? Jan sits himself up and pins my arms to the ground. ‘Wanna fight?’ He smiles menacingly, his panting mouth half-open. He has straight teeth and a broad, glistening lower lip. ‘Wanna fight?’ I know about that game all right. I try cautiously to free myself from his iron grip. I realise that movement by stealth is more effective than fierce resistance. His arms at full stretch, he stares at me triumphantly. I twist about in vain and am ashamed of my cowardliness, of the humiliation. I don’t want to fight, I want Jan as a friend. But I also know that I can only be his real friend if I take up his challenge. ‘Mercy’, says Jan, ‘ask for mercy. Else I won’t let you go.’

‘Come on,’ I plead, ‘we were having such fun.’ With a lightning-like movement I try to wriggle out from under him, but Jan jerks my legs apart with his knees and starts to rub his body against mine. His smile has disappeared and he now has a look of deep concentration as he makes impatient, insistent movements with his hips. He is frightening me. ‘Hey, Jan. Listen…’ He isn’t listening to me. I can see his face above mine, his teeth clenched firmly together and his eyes shut. He has clamped his fingers around my wrists as if he wants to force my hands off. Suddenly he rolls over and kneels next to me. He pulls his trousers down and a stiff little shape swishes up with a slap against his belly.

The two of us stare in silence at the pale thing, raised like a warning finger. I can see the white belly between Jan’s dropped trousers and his pulled-up vest, a white, vulnerable belly. Jan’s prick looks strange, hard and straight with a shiny red rim on top. I wonder if it hurts and give a loud, convulsive swallow.

‘They say you’ve got to push and pull.’ Jan has suddenly become communicative. ‘It works if you do that.’ He begins to tug violently at the swollen thing. I have the feeling that I have ceased to exist, and turn away. What is he doing, what is the matter with him? I feel sorry for him. Is he ill, does he often go on like this? I press my forehead against the ground and inhale the sourish smell of the grass. What exactly was he trying to do? ‘It works if you push and pull,’ the words shoot through my head. What works? He has a secret he won’t tell me, won’t share with me because he thinks I am too childish, because I piss in my bed. When I turn back to him, Jan is standing up, tucking his shirt into his trousers. He holds a hand out to me and pulls me to my feet. ‘Let’s go.’

We trudge up the Cliff. There is no sign of the secret – Jan is his normal, easy-going self.

‘Have you heard anything from home?’

I did get a letter from Amsterdam. Mummy was back, my father had written, and all was well. Was I having a good time, was I staying with nice people? The lady with whom I lived had written to say that I had wet my bed. How had that come about, when I hadn’t done that at home for such a long time? And best regards to Jan, it was nice that we lived so close together. We ought to be pleased that we were away in Friesland because there was hardly anything left to eat in Amsterdam.

But all I can think of is the mysterious event that has just taken place. I am dying to know more, to ask questions. But Jan has suddenly turned tired and surly, he seems to have forgotten the whole thing.

Above, on the road, he stops. ‘So long,’ he says, ‘I’ll take a short cut here.’ He climbs over the fence beside the road and stands still on the other side, as if he were having second thoughts.

‘Come here,’ he says, beckoning brusquely. I walk over to the fence and Jan grabs hold of my throat with both hands. ‘Don’t you dare tell a soul that you’ve seen my prick,’ he whispers, ‘or you’ve had it.’ He pushes me back and runs away across the fields.

On the way back home I keep thinking of Jan’s vulnerable white belly and of the drowned airmen, suspended upside down in the water. Now and then I look around to see if Jan is still in sight. I feel like running after him. I have to protect him, make sure no one dares lay a hand on my friend. No one must ever get to know our secret.

A leaden stillness hangs over the meadows. The cows stand about listlessly on a bare, well-trodden patch where the farmer is about to milk them. It’s late, almost half past five. Hurriedly I race along the dyke.

Chapter 8

The minister’s wife is dead. Mem raises her arms up to heaven with a hoarse cry when she hears the bad news -someone from Warns had come running straight across the fields to our house and banged on the window like one possessed – and then stumbles back into a chair where she sits gasping for breath.

‘Go and fetch Hait,’ she calls to us children, as we stand speechless around her chair. But Jantsje has already rushed off, over the fences and up the road. Her clogs fling lumps of mud up in the air and in her zeal she nearly falls over several times.

At the midday meal Hait prays aloud for the deceased – ‘our dearly beloved and respected late friend,’ he calls her – and for the minister as well.

I had never seen much of the minister’s wife, who had always remained a mysterious and admired stranger in the village. The minister lived across the street from the church in a stately house, a house with stiff white curtains that hung there daintily without creases or stains, and with two flowerless plants on the windowsill, one in front of each pane of glass, exactly in the middle. Behind, you suspected cool rooms, no doubt spotlessly tidy at all times and smelling of beeswax, with gleaming linoleum floors in which the furniture would be reflected.

I had seen the lady occasionally in the garden, cutting roses or raking the gravel. We would make a point when we saw her of walking close alongside the fence and greeting her loudly and insistently. If she greeted us back we would feel a little as if some Higher Being had wished us good morning. She rarely came to church, which I thought a bit strange, but then she probably spoke to the minister so much about God during the week that she had less need for church than the rest of us.

I had learned – thanks in part to her – to tell when people looked ‘townish’. The minister’s wife had been townish: always in proper shoes, always in a smart Sunday dress, and her hair – symmetrical little waves lying like a kind of lid over her head instead of the farmer’s wives’ knot more usual here – was always impeccable. She looked older than the minister, grander: sometimes I thought she could easily have been his mother rather than his wife. The minister would occasionally make a little joke with us and, although his hair was grey, his face looked younger, smooth and carefree, with quick eyes behind gold-framed spectacles.

In Amsterdam, in our street, twins were born not so long ago in Kareltje’s house, next door to Jan. Kareltje’s father was in the police. Two weeks later the twins were dead. ‘On account of the war,’ said my mother, ‘it’s all those rotten Jerries’ fault.’ Two men in black had carried the tiny white boxes out in their arms, with Kareltje and his father and mother the only people following behind.

Appalled, I had watched the mystifyingly sad spectacle, half-hidden behind the front door because I was afraid to be seen staring so shamelessly from the front steps. Dying, what was that?

The day the minister’s wife is buried we are let off school and nobody does any work. We wait by the low church wall until the cortege, black and threatening, approaches, slowly, to the sound of frenziedly chiming church bells.

All the women walking behind the coffin have long black pieces of cloth hanging down from their hats to their waists. We can see Mem in the cortege, wearing her black church clothes and a black straw hat with a veil. I can make out her face through the black cloth, dim and wan. She seems overcome with grief and doesn’t look at us. ‘Mem,’ says Meint and I hear awe in his voice, ‘our Mem.’ I nod respectfully, and swallow.

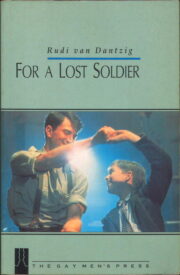

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.