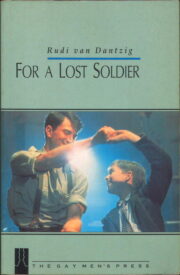

Rudi van Dantzig

FOR A LOST SOLDIER

Translated from the Dutch by Arnold J. Pomerans

For Berendina Hermina, my mother,

and my Frisian foster family, with thanks.

Then they fold their hands in prayer, before their simple repast. And from side to side of the table an invisible cross is cast.

HUNGER WINTER

Chapter 1

The alarm clock goes off at five o’clock in the morning. I stumble out of my little room. A rectangular shape is waiting relentlessly in the semi-darkness of the passage: the suitcase. This is the day then.

The linoleum is chill under my feet. Shivering, I wash in the basin. Even the small stream of tap-water seems noisy. My father walks about in stockinged feet, moving cautiously so as not to wake my little brother. He bends over the kitchen table, cuts a piece of bread in half and gives me a searching look.

‘Are you scared?’

‘No.’ I find it hard to talk, my throat is tight. I push the piece of bread away.

‘Too early for you?’

He helps me put a parting in my hair. I see myself in the mirror, a wan smudge.

Last week at school a nurse had rooted about in my hair with two small glass rods, looking for lice. I had felt her icy feelers make sudden movements with the total single-mindedness of a hunter in pursuit of prey. A little later, sweating, I saw her conferring with the teacher, her eyes fixed on me.

‘I’ve seen enough now, children,’ she said, ‘you’ll hear the results next week.’

What had she seen? My hairless head, shaved bald? ‘Nit king,’ they’d call after you then and wouldn’t let you come anywhere near them.

Luckily I’m leaving, not a moment too soon.

‘Get a move on whispers my father. ‘We’ve got to go.’ The suitcase is standing in the passage by the door, a looming and inescapable presence.

I vanish into my little room to put on my coat. Aimlessly I walk about in the small oblong-shaped space. What am I looking for? Everything has been packed. I yawn soundlessly, nervously. When I go back into the passage, the floorboards make a grating noise, and I know that every joint and crevice in the staircase will creak. I stand still, at a loss for a moment, then I go on down the dark stairs. My feet feel for the treads which I have run up and down confidently hundreds of times a day. My father, turning the key in the door, hisses a warning after me, ‘Hush, the neighbours are still asleep.’

On the second-floor landing I wait for my father, let him walk past me and then follow him down the dark tunnel, one hand anxiously clasping the banister.

The front door stands half open, a beam of early sunshine filled with swirling specks of dust slanting in.

My father hands me the suitcase.

‘You may as well put it down on the pavement.’

I take a few uncertain steps into the deserted street. My long shadow falls brightly outlined across the paving stones. The cool morning air tickles my nose and blows across my bare knees. I sneeze. The sound rebounds against the houses. I lookup at the windows. Some are criss-crossed with strips of brown sticky-tape or covered with rolls of blackout paper. The makeshift pipes of emergency stoves jut out here and there through broken window-panes.

The balcony doors stand open like gaping mouths, breathing stillness and sleep. This is the day then, when I am leaving all this behind. By the time the children in the street wake up I won’t be there any more.

Annie and Willie, Jan, little Karel, Appie: I have gone away. Gone. To the farmers.

I still knew nothing about it up to the day before yesterday. Then one of my father’s colleagues – ‘Frits’, my father called him – had come round. They had gone into the front room to talk with the door closed.

‘Go to your room for a bit. We shan’t be long.’

When Mr Anderson had left, my father came and sat on my bed and put his arm round me. That was odd.

The next morning I watched my father feeding my little I Mother, spoonful by spoonful. Without looking up, he had scraped the empty plate as if trying to scratch the bottom off , and then suddenly he had said, slowly and deliberately, ‘You know, Jeroen, you could go to stay with some farmers for a little while. There’s a lorry leaving on Monday, you can go with it. Lots of food, and playing in the fresh air.’

He had looked at me without conviction, as if he were talking to a stranger.

‘I think you should, you know. It’ll do you good to get away from here for a while. And there’ll be that much more to eat for Bobbie.’

I had said nothing, indifferently drawing little figures on the table with my finger.

‘It won’t be for long, the war will soon be over. They’re already in France. And then you’ll be back home.’

I look up at our balcony where the curtain is billowing in the wind. Behind it my little brother is asleep in the small side-room. If he should wake up suddenly and start to cry there’ll be no one to lift him out of his cradle. He’ll bawl the place down.

Leaving home, something I had at first sensed dully and vaguely, now hits me with full force. Tension seizes me between the eyebrows, terror reverberates in the aching hollow of my belly. My body contracts, I feel as if I’m going to be sick.

My father comes out with the bicycle, pulls the door shut softly behind him and parks the bicycle at the kerb as quietly as he can. His face is drawn and tired.

I climb on to the luggage carrier and my father places the suitcase between us. I move back a little; the bars of the carrier press coldly against my behind, the edge of the suitcase cuts into my thighs.

We take off with an awkward wobble, the iron rims rattling across the cobblestones. With each bump I shrink more into myself, clinging tightly to my father’s coat.

Before we clatter around the corner I take a last look at our window, our balcony. The sunlight is reflected by the glass and the white net curtain waves like a pale hand. Bye.

We take Admiraal de and then the . I have never seen the streets so empty, so deserted. The rusty tram-lines stretch out far down the road. We get off the bicycle at a broken piece of road full of sandy potholes and walk along the pavement. I have trouble balancing the suitcase on the carrier. Why are we in such a hurry?

We walk past an empty house. Through the smashed window-panes I can see a man and a woman down on their knees. They are prising planks out of the floor. As we walk by, they stop panic-stricken. The woman presses herself against the floor trying to hide from us. Ashamed of our indiscreet staring, I turn my head away.

‘The lorry is on the Dam, near the Royal Palace,’ my father says. ‘At least it had better be there by now, or else you’ll just have to wait by yourself. I’ll have to get back straight away, on account of the Jerries. And Bobbie’ll be waking up soon.’

People have formed a silent queue outside a dilapidated shop with a dingy display window. It seems to have been disused for some time. We rattle past. I catch the eye of a man leaning against the wall. He has a distant, grey look.

I want to go back, I don’t want to leave. The lorry surely won’t be there yet, it’s too early.

But then, on the shady side of the Palace, I see it: a pick-up truck with a canvas cover over the loading platform. A man is sitting slumped in the cab, looking straight in front of him through the filthy windscreen.

‘Is this the lorry for Friesland, for the Fokker children?’

The man has sleepy eyes. He mumbles something to my father that I can’t catch. Perhaps we are wrong, perhaps the whole thing is a mistake.

We go to the back of the lorry and my father hoists my suitcase over the tail-board.

‘What do you want to do, wait outside or shall I help you in?’

I look at how high the back of the lorry is. I won’t be able to get up there by myself.

‘Please lift me in.’

The iron floor is cold against my knees. There is a pile of grey blankets in a corner, but I daren’t take one.

‘Daddy.’

My father has gone back to the front of the lorry and is looking to the driver again.

‘Daddy, I don’t feel very well. I’d better go back with you, I’m beginning to feel really sick.’

If it had been my mother I would have burst into loud, heart-rending sobs and clung tightly to her. She would have taken me back home with her.

‘Chin up, my boy.’ My father hands me a registration card with a few sheets of ration coupons attached to it. ‘Look after these because they’re going to want them in Friesland. Don’t lose them, whatever you do.’

He hoists himself up on to the tail-board and I throw my ,arms around his neck. ‘Take care, won’t you. And write.’

I can’t get an answer out. My body is trembling with pent-up terror. Through a haze I watch the blue of his coat receding from the lorry. A wave of his arm, lit brightly by the Bun, and then he is round the corner. Gone.

The man in the cab taps against the window.

‘It won’t be long now,’ he calls out, ‘just as soon as everybody turns up.’

The lorry door slams shut. A couple of sparrows are chirping in the sun on the other side of the street. I crawl to the furthest corner of the platform and position the suitcase next to me. I draw my knees up and feel a drop falling onto my leg and trickling down along my thigh.

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.