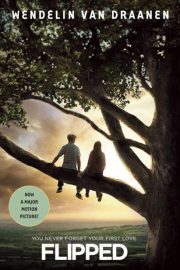

At first I just wanted to see how high I could get before the bus pulled up, but before long I was leaving the house early so I could get clear up to my spot to see the sun rise, or the birds flutter about, or just the other kids converge on the curb.

I tried to convince the kids at the bus stop to climb up with me, even a little ways, but all of them said they didn’t want to get dirty. Turn down a chance to feel magic for fear of a little dirt? I couldn’t believe it.

I’d never told my mother about climbing the tree. Being the truly sensible adult that she is, she would have told me it was too dangerous. My brothers, being brothers, wouldn’t have cared.

That left my father. The one person I knew would understand. Still, I was afraid to tell him. He’d tell my mother and pretty soon they’d insist that I stop. So I kept quiet, kept climbing, and felt a somewhat lonely joy as I looked out over the world.

Then a few months ago I found myself talking to the tree. An entire conversation, just me and a tree. And on the climb down I felt like crying. Why didn’t I have someone real to talk to? Why didn’t I have a best friend like everyone else seemed to? Sure, there were kids I knew at school, but none of them were close friends. They’d have no interest in climbing the tree. In smelling the sunshine.

That night after dinner my father went outside to paint. In the cold of the night, under the glare of the porch light, he went out to put the finishing touches on a sunrise he’d been working on.

I got my jacket and went out to sit beside him, quiet as a mouse.

After a few minutes he said, “What’s on your mind, sweetheart?”

In all the times I’d sat out there with him, he’d never asked me that. I looked at him but couldn’t seem to speak.

He mixed two hues of orange together, and very softly he said, “Talk to me.”

I sighed so heavily it surprised even me. “I understand why you come out here, Dad.”

He tried kidding me. “Would you mind explaining it to your mother?”

“Really, Dad. I understand now about the whole being greater than the sum of the parts.”

He stopped mixing. “You do? What happened? Tell me about it!”

So I told him about the sycamore tree. About the view and the sounds and the colors and the wind, and how being up so high felt like flying. Felt like magic.

He didn’t interrupt me once, and when my confession was through, I looked at him and whispered, “Would you climb up there with me?”

He thought about this a long time, then smiled and said, “I’m not much of a climber anymore, Julianna, but I’ll give it a shot, sure. How about this weekend, when we’ve got lots of daylight to work with?”

“Great!”

I went to bed so excited that I don’t think I slept more than five minutes the whole night. Saturday was right around the corner. I couldn’t wait!

The next morning I raced to the bus stop extra early and climbed the tree. I caught the sun rising through the clouds, sending streaks of fire from one end of the world to the other. And I was in the middle of making a mental list of all the things I was going to show my father when I heard a noise below.

I looked down, and parked right beneath me were two trucks. Big trucks. One of them was towing a long, empty trailer, and the other had a cherry picker on it—the kind they use to work on overhead power lines and telephone poles.

There were four men standing around talking, drinking from thermoses, and I almost called down to them, “I’m sorry, but you can’t park there…. That’s a bus stop!” But before I could, one of the men reached into the back of a truck and started unloading tools. Gloves. Ropes. A chain. Earmuffs. And then chain saws. Three chain saws.

And still I didn’t get it. I kept looking around for what it was they could possibly be there to cut down. Then one of the kids who rides the bus showed up and started talking to them, and pretty soon he was pointing up at me.

One of the men called, “Hey! You better come down from there. We gotta take this thing down.”

I held on to the branch tight, because suddenly it felt as though I might fall. I managed to choke out, “The tree?”

“Yeah, now come on down.”

“But who told you to cut it down?”

“The owner!” he called back.

“But why?”

Even from forty feet up I could see him scowl. “Because he’s gonna build himself a house, and he can’t very well do that with this tree in the way. Now come on, girl, we’ve got work to do!”

By that time most of the kids had gathered for the bus. They weren’t saying anything to me, just looking up at me and turning from time to time to talk to each other. Then Bryce appeared, so I knew the bus was about to arrive. I searched across the rooftops and sure enough, there it was, less than four blocks away.

My heart was crazy with panic. I didn’t know what to do! I couldn’t leave and let them cut down the tree! I cried, “You can’t cut it down! You just can’t!”

One of the men shook his head and said, “I am this close to calling the police. You are trespassing and obstructing progress on a contracted job. Now are you going to come down or are we going to cut you down?”

The bus was three blocks away. I’d never missed school for any reason other than legitimate illness, but I knew in my heart that I was going to miss my ride. “You’re going to have to cut me down!” I yelled. Then I had an idea. They’d never cut it down if all of us were in the tree. They’d have to listen! “Hey, guys!” I called to my classmates. “Get up here with me! They can’t cut it down if we’re all up here! Marcia! Tony! Bryce! C’mon, you guys, don’t let them do this!”

They just stood there, staring up at me.

I could see the bus, one block away. “Come on, you guys! You don’t have to come up this high. Just a little ways. Please!”

The bus blasted up and pulled to the curb in front of the trucks, and when the doors folded open, one by one my classmates climbed on board.

"Flipped" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Flipped". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Flipped" друзьям в соцсетях.