“Yeah,” my father said. “Patsy tells me you’ve been over there all afternoon. If you were in the mood for home improvement projects, why didn’t you just say so?”

My father was just joking around, but I don’t think my grandfather took it that way. He helped himself to a cheese-stuffed potato and said, “Pass the salt, won’t you, Bryce?”

So there was this definite tension between my father and my grandfather, but I think if Dad had dropped the subject right then, the vibe would’ve vanished.

Dad didn’t drop it, though. Instead, he said, “So why’s the girl the one who’s finally doing something about their place?”

My grandfather salted his potato very carefully, then looked across the table at me. Ah-oh, I thought. Ah-oh. In a flash I knew those stupid eggs were not behind me. Two years of sneaking them in the trash, two years of avoiding discussion of Juli and her eggs and her chickens and her early-morning visits, and for what? Granddad knew, I could see it in his eyes. In a matter of seconds he’d crack open the truth, and I’d be as good as fried.

Enter a miracle. My grandfather petrified me for a minute with his eyes but then turned to my father and said, “She wants to, is all.”

A raging river of sweat ran down my temples, and as my father said, “Well, it’s about time someone did,” my grandfather looked back at me and I knew—he was not going to let me forget this. We’d just had another conversation, only this time I was definitely not dismissed.

After the dishes were cleared, I retreated to my room, but my grandfather came right in, closed the door behind him, and then sat on my bed. He did this all without making a sound. No squeaking, no clanking, no scraping, no breathing… I swear, the guy moved through my room like a ghost.

And of course I’m banging my knee and dropping my pencil and deteriorating into a pathetic pool of Jell-O. But I tried my best to sound cool as I said, “Hello, Granddad. Come to check out the digs?”

He pinched his lips together and looked at nothing but me.

I cracked. “Look, Granddad, I know I messed up. I should’ve just told her, but I couldn’t. And I kept thinking they’d stop. I mean, how long can a chicken lay eggs? Those things hatched in the fifth grade! That was like, three years ago! Don’t they eventually run out? And what was I supposed to do? Tell her Mom was afraid of salmonella poisoning? And Dad wanted me to tell her we were allergic—c’mon, who’s going to buy that? So I just kept, you know, throwing them out. I didn’t know she could’ve sold them. I thought they were just extras.”

He was nodding, but very slowly.

I sighed and said, “Thank you for not saying anything about it at dinner. I owe you.”

He pulled my curtain aside and looked across the street. “One’s character is set at an early age, son. The choices you make now will affect you for the rest of your life.” He was quiet for a minute, then dropped the curtain and said, “I hate to see you swim out so far you can’t swim back.”

“Yes, sir.”

He frowned and said, “Don’t yes-sir me, Bryce.” Then he stood and added, “Just think about what I’ve said, and the next time you’re faced with a choice, do the right thing. It hurts everyone less in the long run.”

With that, poof, he was gone.

The next day I went to shoot some hoops at Garrett’s after school, and when his mom dropped me off later that afternoon, my granddad didn’t even notice. He was too busy being Joe Carpenter in Juli’s front yard.

I tried to do my homework at the breakfast bar, but my mom came home from work and started being all chatty, and then Lynetta appeared and the two of them started fighting about whether Lynetta’s makeup made her look like a wounded raccoon.

Lynetta. I swear she’ll never learn.

I packed up my stuff and escaped to my room, which, of course, was a total waste. They’ve got a saw revving and wailing across the street, and in between cuts I can hear the whack, whack, whack! whack, whack, whack! of a hammer. I look out the window and there’s Juli, spitting out nails and slamming them in place. No kidding. She’s got nails lined up between her lips like steel cigarettes, and she’s swinging that hammer full-arc, way above her head, driving nails into pickets like they’re going into butter.

For a split second there, I saw my head as the recipient of her hammer, cracking open like Humpty Dumpty. I shuddered and dropped the curtain, ditched the homework, and headed for the TV.

They handymanned all week. And every night Granddad would come in with rosy cheeks and a huge appetite and compliment my mom on what a great cook she was. Then Saturday happened. And the last thing I wanted was to spend the day at home while my grandfather churned up dirt and helped plant Juli’s yard. Mom tried to get me to do our own yard, but I would have felt ridiculous micromowing our grass with Granddad and Juli making real changes right across the street.

So I locked myself in my room and called Garrett. He wasn’t home, and everybody else I called had stuff they had to do. And hitting up Mom or Dad for a ride to the movies or the mall was hopeless. They’d tell me I was supposed to be doing the yard.

What I was, was stuck.

And what I wound up doing was looking out the stupid window at Juli and my grandfather. It was a totally lame thing to do, but that’s what I did.

I got nailed doing it, too. By my grandfather. And he, of course, had to point me out to Juli, which made me feel another two inches shorter. I dropped the curtain and blasted out the back door and over the fence. I had to get out of there.

I swear I walked ten miles that day. And I don’t know who I was madder at — my grandfather, Juli, or me. What was wrong with me? If I wanted to make it up to Juli, why didn’t I just go over there and help? What was stopping me?

I wound up at Garrett’s house, and man, I’d never been so glad to see anyone in my life. Leave it to Garrett to get your mind off anything important. That dude’s the master. We went out back and shot hoops, watched the tube, and talked about hitting the water slides this summer.

And when I got home, there was Juli, sprinkling the yard.

She saw me, all right, but she didn’t wave or smile or anything. She just looked away.

Normally what I’d do in that situation is maybe pretend like I hadn’t seen her, or give a quick wave and charge inside. But she’d been mad at me for what seemed like ages. She hadn’t said word one to me since the morning of the eggs. She’d completely dissed me in math a couple days before when I’d smiled at her, trying to tell her I was sorry. She didn’t smile back or nod or anything. She just turned away and never looked back.

I even waited for her outside the classroom to say something, anything, about her fixing up the yard and how bad I felt, but she ditched me out the other door, and after that anytime I got anywhere near her, she’d find some way to skate around me.

So there she was, watering the yard, making me feel like a jerk, and I’d had enough of it. I went up to her and said, “It’s looking real good, Juli. Nice job.”

“Thanks,” she said without smiling. “Chet did most of it.”

Chet? I thought. Chet? What was she doing, calling my grandfather by his first name? “Look, Juli,” I said, trying to get on with why I was there. “I’m sorry for what I did.”

She looked at me for a second, then went back to watching the water spray across the dirt. Finally she said, “I still don’t get it, Bryce. Why didn’t you just tell me?”

“I… I don’t know. It was dumb. I should have. And I shouldn’t have said anything about the yard, either. It was, you know, out of line.”

I was already feeling better. A lot better. Then Juli says, “Well, maybe it’s all for the better,” and starts bouncing up and down on the balls of her feet, acting more like her old self. “Doesn’t it look great? I learned so much from Chet it’s amazing. You are so lucky. I don’t even have grandparents anymore.”

“Oh,” I said, not knowing what to say.

“I do feel sorry for him, though. He sure misses your grandmother.” Then she laughs and shakes her head, saying, “Can you believe it? He says I remind him of her.”

“What?”

“Yeah,” she laughs again. “That’s what I said. But he meant it in a nice way.”

I looked at Juli and tried to picture my grandmother as an eighth grader. It was hopeless. I mean, Juli’s got long, fluffy brown hair and a nose full of freckles, where my grandmother had always been some variety of blond. And my grandmother had used powder. Puffy white powder. She’d put it on her face and in her hair, in her slippers and on her chest…. That woman powdered everything.

I could not see Juli coated in powder. Okay, maybe gun powder, but the white perfumy stuff? Forget it.

I guess I was staring, because Juli says, “Look, I didn’t say it, he did. I just thought it was nice, that’s all.”

“Yeah, whatever. Well, good luck with the grass. I’m sure it’ll come up great.” Then I totally surprised myself by saying, “Knowing you, you’ll get ’em all to hatch.” I didn’t say it mean or anything, I really meant it. I laughed, and then she laughed, and that’s how I left her—sprinkling her soon-to-be sod, smiling.

I hadn’t been in such a good mood in weeks. The eggs were finally behind me. I was absolved. Relieved. Happy.

It took me a few minutes at the dinner table to realize that I was the only one who was. Lynetta had on her usual pout, so that wasn’t it. But my father’s idea of saying hello was to lay into me about the lawn.

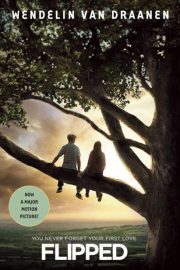

"Flipped" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Flipped". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Flipped" друзьям в соцсетях.