I was supposed to control humidity, too, or horrible things would happen to the chick. Too dry and the chick couldn’t peck out; too wet and it would die of mushy chick disease. Mushy chick disease?!

My mother, being the sensible person that she is, told me to tell Mrs. Brubeck that I simply wouldn’t be hatching a chick. “Have you considered growing beans?” she asked me.

My father, however, understood that you can’t refuse to do your teacher’s assignment, and he promised to help. “An incubator’s not difficult to build. We’ll make one after dinner.”

How my father knows exactly where things are in our garage is one of the wonders of the universe. How he knew about incubators, however, was revealed to me while he was drilling a one-inch hole in an old scrap of Plexiglas. “I raised a duck from an egg when I was in high school.” He grinned at me. “Science fair project.”

“A duck?”

“Yes, but the principle is the same for all poultry. Keep the temperature constant and the humidity right, turn the egg several times a day, and in a few weeks you’ll have yourself a little peeper.”

He handed me a lightbulb and an extension cord with a socket attached. “Fasten this through the hole in the Plexiglas. I’ll find some thermometers.”

“Some? We need more than one?”

“We have to make you a hygrometer.”

“A hygrometer?” “To check the humidity inside the incubator. It’s just a thermometer with wet gauze around the bulb.”

I smiled. “No mushy chick disease?”

He smiled back. “Precisely.”

By the next afternoon I had not one, but six chicken eggs incubating at a cozy 102 degrees Fahrenheit. “They don’t all make it, Juli,” Mrs. Brubeck told me. “Hope for one. The record’s three. The grade’s in the documentation. Be a scientist. Good luck.” And with that, she was off.

Documentation? Of what? I had to turn the eggs three times a day and regulate the temperature and humidity, but aside from that what was there to do?

That night my father came out to the garage with a cardboard tube and a flashlight. He taped the two together so that the light beam was forced straight out the tube. “Let me show you how to candle an egg,” he said, then switched off the garage light.

I’d seen a section on candling eggs in Mrs. Brubeck’s book, but I hadn’t really read it yet. “Why do they call it that?” I asked him. “And why do you do it?”

“People used candles to do this before they had incandescent lighting.” He held an egg up to the cardboard tube. “The light lets you see through the shell so you can watch the embryo develop. Then you can cull the weak ones, if necessary.”

“Kill them?”

“Cull them. Remove the ones that don’t develop properly.”

“But… wouldn’t that also kill them?”

He looked at me. “Leaving an egg you should cull might have disastrous results on the healthy ones.”

“Why? Wouldn’t it just not hatch?”

He went back to lighting up the egg. “It might explode and contaminate the other eggs with bacteria.”

Explode! Between mushy chick disease, exploding eggs, and culling, this project was turning out to be the worst! Then my father said, “Look here, Julianna. You can see the embryo.” He held the flashlight and egg out so I could see.

I looked inside and he said, “See the dark spot there? In the middle? With all the veins leading to it?”

“The thing that looks like a bean?”

“That’s it!”

Suddenly it felt real. This egg was alive. I quickly checked the rest of the group. There were little bean babies in all of them! Surely they had to live. Surely they would all make it!

“Dad? Can I take the incubator inside? It might get too cold out here at night, don’t you think?”

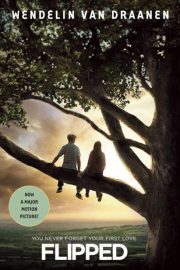

"Flipped" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Flipped". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Flipped" друзьям в соцсетях.