Garrett got me back on track. “They’re all chickens,” he says. “Look at ’em.”

I quit checking out Juli’s shoes and started checking out birds. The first thing I did was count them. One-two-three-four-five-six. All accounted for. After all, how could anyone forget she’d hatched six? It was the all-time school record — everyone in the county had heard about that.

But I was not really sure how to ask Garrett about what he had said. Yeah, they were all chickens, but what did that mean? I sure didn’t want him coming down on me again, but it still didn’t make sense. Finally I asked him, “You mean there’s no rooster?”

“Correctomundo.”

“How can you tell?”

He shrugged. “Roosters strut.”

“Strut.”

“That’s right. And look — none of them have long feathers. Or very much of that rubbery red stuff.” He nodded. “Yeah. They’re definitely all chickens.”

That night my father got right to the point. “So, son, mission accomplished?” he asked as he stabbed into a mountain of fettuccine and whirled his fork around.

I attacked my noodles too and gave him a smile. “Uhhuh,” I said as I sat up tall to deliver the news. “They’re all chickens.”

The turning of his fork came to a grinding halt. “And… ?”

I could tell something was wrong, but I didn’t know what. I tried to keep the smile plastered on my face as I said, “And what?”

He rested his fork and stared at me. “Is that what she said? ‘They’re all chickens’?”

“Uh, not exactly.”

“Then exactly what did she say?”

“Uh… she didn’t exactly say anything.”

“Meaning?”

“Meaning I went over there and took a look for myself.” I tried very hard to sound like this was a major accomplishment, but he wasn’t buying.

“You didn’t ask her?”

“I didn’t have to. Garrett knows a lot about chickens, and we went over there and found out for ourselves.”

Lynetta came back from rinsing the Romano sauce off her seven and a half noodles, then reached for the salt and scowled at me, saying, “You’re the chicken.”

“Lynetta!” my mother said. “Be nice.”

Lynetta stopped shaking the salt. “Mother, he spied. You get it? He went over there and looked over the fence. Are you saying you’re okay with that?”

My mom turned to me. “Bryce? Is that true?”

Everyone was staring at me now, and I felt like I had to save face. “What’s the big deal? You told me to find out about her chickens, and I found out about her chickens!”

“Brawk-brawk-brawk!” my sister whispered.

My father still wasn’t eating. “And what you found out,” he said, like he was measuring every word, “was that they’re all… chickens.”

“Right.”

He sighed, then took that bite of noodles and chewed it for the longest time.

It felt like I was sinking fast, but I couldn’t figure out why. So I tried to bail out with, “And you guys can go ahead and eat those eggs, but there’s no way I’m going to touch them, so don’t even ask.”

My mother’s looking back and forth from my dad to me while she eats her salad, and I can tell she’s waiting for him to address my adventure as a neighborhood operative. But since he’s not saying anything, she clears her throat and says, “Why’s that?”

“Because there’s… well, there’s… I don’t know how to say this nicely.”

“Just say it,” my father snaps.

“Well, there’s, you know, excrement everywhere.”

“Oh, gross!” my sister says, throwing down her fork.

“You mean chicken droppings?” my mother asks.

“Yeah. There’s not even a lawn. It’s all dirt and, uh, you know, chicken turds. The chickens walk in it and peck through it and… ”

“Oh, gross!” Lynetta wails.

“Well, it’s true!”

Lynetta stands up and says, “You expect me to eat after this?” and stalks out of the room.

“Lynetta! You have to eat something,” my mother calls after her.

“No, I don’t!” she shouts back; then a second later she sticks her head back into the dining room and says, “And don’t expect me to eat any of those eggs either, Mother. Does the word salmonella mean anything to you?”

Lynetta takes off down the hall and my mother says, “Salmonella?” She turns to my father. “Do you suppose they could have salmonella?”

“I don’t know, Patsy. I’m more concerned that our son is a coward.”

“A coward! Rick, please. Bryce is no such thing. He’s a wonderful child who’s—”

“Who’s afraid of a girl.”

“Dad, I’m not afraid of her, she just bugs me!”

“Why?”

“You know why! She bugs you, too. She’s over the top about everything!”

“Bryce, I asked you to conquer your fear, but all you did was give in to it. If you were in love with her, that would be one thing. Love is something to be afraid of, but this, this is embarrassing. So she talks too much, so she’s too enthused about every little thing, so what? Get in, get your question answered, and get out. Stand up to her, for cryin’ out loud!”

“Rick…,” my mom was saying, “Rick, calm down. He did find out what you asked him to—”

“No, he didn’t!”

“What do you mean?”

“He tells me they’re all chickens! Of course they’re all chickens! The question is how many are hens, and how many are roosters.”

I could almost hear the click in my brain, and man, I felt like a complete doofus. No wonder he was disgusted with me. I was an idiot! They were all chickens… du-uh! Garrett acted like he was some expert on chickens, and he didn’t know diddly-squat! Why had I listened to him?

But it was too late. My dad was convinced I was a coward, and to get me over it, he decided that what I should do was take the carton of eggs back to the Bakers and tell them we didn’t eat eggs, or that we were allergic to them, or something.

Then my mom butts in with, “What are you teaching him here, Rick? None of that is true. If he returns them, shouldn’t he tell them the truth?”

“What, that you’re afraid of salmonella poisoning?”

“Me? Aren’t you a little concerned, too?”

“Patsy, that’s not the point. The point is, I will not have a coward for a son!”

“But teaching him to lie?”

“Fine. Then just throw them away. But from now on I expect you to look that little tiger square in the eye, you hear me?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Okay, then.”

I was off the hook for all of about eight days. Then there she was again, at seven in the morning, bouncing up and down on our porch with eggs in her hands. “Hi, Bryce! Here you go.”

I tried to look her square in the eye and tell her, No thanks, but she was so darned happy, and I wasn’t really awake enough to tackle the tiger. She wound up pushing another carton into my hands, and I wound up ditching them in the kitchen trash before my father sat down to breakfast.

This went on for two years. Two years! And it got to a point where it was just part of my morning routine. I’d be on the lookout for Juli so I could whip the door open before she had the chance to knock or ring the bell, and then I’d bury the eggs in the trash before my dad showed up.

Then came the day I blew it. Juli’d actually been making herself pretty scarce because it was around the time they’d taken the sycamore tree down, but suddenly one morning she was back on our doorstep, delivering eggs. I took them, as usual, and I went to chuck them, as usual. But the kitchen trash was so full that there wasn’t any room for the carton, so I put it on top, picked up the trash, and beat it out the front door to empty everything into the garbage can outside.

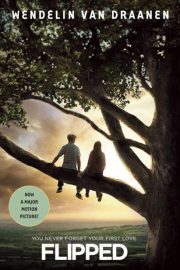

"Flipped" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Flipped". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Flipped" друзьям в соцсетях.