Chapter II

THE DAUPHINE AT VERSAILLES

It was not long before Antoinette realised that life at Versailles was not going to be very different from that in the Schönbrunn Palace, for her mother had sent strict instructions as to how her education was to be conducted; she had even sent the Abbé de Vermond, that her daughter might continue to study under him. She had written to the King of France to the effect that her daughter was very young and that marriage had interrupted her education; she wished her therefore to live as quietly as possible in her new home until she was mature enough to fit her new position with grace.

The King had readily agreed. He was too indolent to concern himself with the upbringing of his new granddaughter and quite prepared to let her mother continue with the responsibility.

What Maria Theresa did not realise was that, although it was a comparatively easy matter to keep her daughter childish in her own Court, in the brilliant one at Versailles – where amours were the order of the day and the reflection of all that wit and brilliance which had graced the Court of Le Roi Soleil still lingered – the young girl was bound to find the life planned for her irksome.

There was intrigue all about her.

She quickly discovered this when, on the morning after her wedding night, she was visited by the three aunts, ‘Les Mesdames’ as they were called throughout the Court.

Madame Adelaide, the eldest of the three unmarried daughters of Louis Quinze, was clearly the most dominant; Madame Victoire was kind but neurotic and apt to panic at the slightest difficulty; Madame Sophie was the ugliest of the three and, being constantly aware of this, was very shy. The two younger sisters were very much under the influence of the eldest, and the three were more often than not in each other’s company. The whole Court, following the King’s example, was inclined to treat them with ridicule. They were Princesses for whom husbands had not been found; they were middle-aged and far from prepossessing; and they had been foolish enough to band themselves together against the King’s mistresses. They should have known better, and suffered accordingly.

They were pious and disapproving, and Adelaide, unable to stop herself meddling in Court intrigue, carried her sisters along with her.

Madame Adelaide had deeply resented the Austrian marriage and was determined to hate Antoinette. But, as she told her sisters, ‘This we must hide, for through the child we may discover a great deal.’

So together they visited her as she sat with the Abbé de Vermond, wondering what difference there was after all in being Dauphine of France instead of Archduchess of Austria.

The aunts entered with ceremony: Adelaide first, Victoire next, and Sophie bringing up the rear.

The Abbé rose at the sight of the Princesses. He bowed low, but they ignored him.

Antoinette rose also; she curtsied, and Adelaide patted her cheek.

‘We have come to pay our respects to our little Dauphine,’ said Adelaide.

‘Thank you, Mesdames,’ replied Antoinette.

Adelaide bowed her head in acknowledgement of the thanks. Victoire did the same, and a few seconds later so did Sophie. They looked so odd, three middle-aged ladies very much alike, standing there nodding, that Antoinette found it difficult to restrain her laughter.

Adelaide turned to the Abbé; she did not speak; she merely gave him a haughty look. He said: ‘You wish to be alone with the Dauphine, Madame?’

Adelaide nodded her head, while the other two imitated their sister’s haughty look.

The Abbé bowed and left them. He had been warned to be very careful not to offend French etiquette.

‘Now the man has gone,’ said Adelaide, ‘you may call us Tantes. I am Tante Adelaide, dear child.’

‘And I am Tante Victoire,’ said the second.

‘And I am Tante Sophie,’ murmured the third.

‘My dear Tantes, I welcome you all,’ said Antoinette. She stood on tiptoe and kissed them in order of seniority.

‘That is charming,’ said Tante Adelaide.

‘Charming!’ ‘Charming!’ echoed Victoire and Sophie.

‘We are going to be friends … very dear friends,’ said Adelaide.

Antoinette found herself looking at the others for the confirmation she expected. ‘That is why we come to you at once …’ went on Adelaide.

‘Before others contaminate you,’ put in Victoire.

‘Be silent, Victoire!’ said Adelaide sharply. ‘But your Tante Victoire is not far wrong, my child. There is much evil at the Court of France. You are a good and virtuous girl. I see that.’ Again Antoinette looked quickly at the others. They nodded, implying that they too found her a good and virtuous girl. ‘And you, my dear, began to uncover a little of that evil during the banquet.’

The others tittered, but Adelaide held up a warning hand. Antoinette was fascinated by the way in which the other two immediately obeyed their leader. They were serious at once.

‘You wondered about that coarse creature who had the temerity to sit at table with us.’

‘Yes. Who was she?’

‘She is known as the Comtesse du Barry.’

‘And she is a member of the royal family?’

‘A member of the royal family! Indeed she is not. The King, our father – and although he is our father we say this, for, my dear, we will have truth however unpleasant that truth may be – the King has strange habits. He has taken that creature from the gutter, and she shares his life. Do you know what we mean?’

‘She … lives as one of the family?’

‘As its most important member.’

‘But why so … since she is vulgar, as you say? Why does the King like her so much?’

‘Men are weak,’ said Adelaide; her sisters nodded in agreement.

Antoinette looked in astonishment from one to another of the three aunts, who continued to nod vigorously.

‘The woman shares the King’s bed … as you do the Dauphin’s,’ said Victoire, quickly putting her hand to her mouth.

Adelaide’s eyebrows shot up, and she looked very angry.

‘That is quite different,’ she said sternly. ‘Our little Dauphine is married to Berry. That woman … is not married to our father.’

‘Then she is …’ began Antoinette.

Adelaide put her fingers on her lips. She brought her face close to Antoinette’s ear. Antoinette looked at the skin which lay like grey crêpe beneath her sly, narrow eyes, and shuddered.

‘A harlot!’ she whispered; then she drew herself up and went on. ‘But we will not speak of it. It is too shocking. I rejoice that we are here to protect you from evil things. Our sister Louise is a Carmelite nun. She often declares that the King will fall on evil times if he does not give up that woman. But we will defeat her yet. She hates us … because she is evil and we have always lived virtuous lives. We have come to advise you, my dear.’

‘Do not let that woman come near you,’ cried Victoire shrilly.

‘How can she help that?’ enquired Sophie.

‘She must ignore her as best she can,’ said Adelaide. ‘Be cold to her. Do not confide in her. If you wish to confide in any, remember your three aunts who will be most anxious to help you.’

‘You are very kind,’ said Antoinette.

They nodded in unison.

‘Don’t forget. If you are in difficulty, come to Tante Adelaide … ’

‘And Tante Victoire. Please do not forget Tante Victoire.’

‘And Tante Sophie,’ whispered the youngest aunt.

‘For,’ went on Adelaide, ‘we are after all poor Berry’s own aunts.’

‘Why do you call him poor?’ asked Antoinette.

‘The King, our father, always calls him Poor Berry,’ said Victoire.

‘He was always a quiet boy – not like his brothers,’ Adelaide whispered. ‘He was always timid … never wanted to play with other boys.’

‘He was born like it,’ said Victoire. ‘Always quiet, always dull. Poor Berry!’

‘Poor Berry!’ echoed Sophie.

‘His father died when he was eleven,’ went on Adelaide. ‘His father was wonderful. Had he lived, everything would have been so different.’ The aunts with one accord dabbed their eyes. ‘But he died of consumption when he was quite young. He said: “I am dying without having enjoyed anything, and without having done any good to anyone.” ’

‘He was thirty-six,’ said Sophie.

Adelaide continued: ‘It happened quite suddenly, and his wife followed him quickly to the grave. She suffered from the same disease … and those poor children were orphans.’

‘They had their aunts,’ said Victoire with a nervous titter.

‘Yes, they had us. We have been mothers … mothers … to those poor orphans.’

‘Then they have not been so unfortunate,’ said Antoinette. ‘In place of one mother they have had three.’

‘That is so; Berry’s two elder brothers both died. Bourgogne was nine when he died; Aquitaine but five months old.’

‘That made Berry Dauphin,’ said Victoire.

‘Poor Berry!’ chanted Sophie.

‘His father supervised his education,’ put in Adelaide, determined to dominate the conversation. ‘He made him work hard. He was fond of his books. I do not know why he should appear so dull. It is perhaps because his brothers talk so much … and are so gay … particularly Artois. Did you not think Artois handsome? But I know you did. I saw you looking at him.’ Adelaide’s eyes were wicked suddenly. ‘Yes, I saw you looking at Artois. It is true he is younger than his brother, but not much younger than you. Were you wishing that Artois was the Dauphin … eh? Were you wishing the Archbishop was sprinkling holy water on a bed you would share with him, eh?’

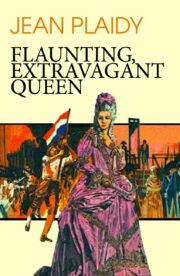

"Flaunting, Extravagant Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Flaunting, Extravagant Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Flaunting, Extravagant Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.