‘What else she give you, eh?’ The woman Tison was feeling in their pockets, her mouth tight, her eyes shining; she was hoping to find some message on the boys which the Queen had given them. Disappointed she said: ‘Well, don’t stand there looking as though you are in the presence of the Almighty. We’re all equal now, you know.’ The Queen smiled at the boys as though the woman had not spoken; and Toulan continued to look at the boys.

The next day the lamplighter came alone. The Queen was disappointed. She had liked to see the children.

She noticed that he fumbled with the lamps, and when she looked at him more closely she saw that he was a new man.

The woman Tison was in the next room and the lamplighter moved closer to the Queen. He whispered: ‘Your Majesty, Toulan persuaded the lamplighter to allow me to come in his place. We bribed him. I told him that I was eager to see the prison and the Queen. He is now enjoying himself in a tavern. I had to see you for myself to make certain that I could trust Toulan.’

‘You are …’

‘Jarjayes.’

‘My dear General …’

‘Madame, it is my earnest wish to free you from this place. I have been in touch with the Comte de Fersen. He will not rest until you are free.’

In that moment the Queen felt again a desire to live. The thought of possible escape lifted her spirits and it seemed to her that life could still hold some meaning for her.

‘We have to work this out with the utmost care. Toulan thinks that Lepître, the commissioner of the prison, may help. Everything depends on this man and whether he is amenable to bribes.’

‘I understand,’ said the Queen. ‘Have a care. The Tison woman watches continually.’

‘Ask me questions about my children and we will talk under cover of that.’

The Queen did so, and Jarjayes answered, interspersing his answers with an account of what they planned, keeping his eyes on the door while he talked, for fear Madame Tison should make an appearance.

It might be possible for the Queen and Madame Elisabeth to leave the prison disguised as municipal councillors, with large hats, cloaks, big boots and of course the sash of the tricolor. They would need not only forged passports but the cooperation of Lepître, the only man who could conduct them out of the prison.

‘My children …’ murmured the Queen.

‘I would come as the lamplighter, bringing clothes for the Dauphin and Madame Royale, so that they would look exactly like the lamplighter’s children. I should lead them out with me.’

‘And the Tisons?’

‘We should have to find some means of drugging them.’

‘They take snuff,’ said the Queen.

‘Drugged snuff would be the answer. I dare stay no longer. Be ready. I trust it will be soon.’

Lepître had been a schoolmaster before the revolution. He was a sick man, pale, delicate from childhood, and he longed to get away from the town and live in the country; but he needed money to do this.

It was a daring scheme and Lepître was not a daring man. If he were discovered leading the two most important prisoners out of the prison, what would happen to him? When he considered that, he trembled with fear.

He dared not do this thing. Yet if he had the money, if he escaped with them, he could live in quiet in the country for the rest of his life. He was not a violent man; he could not endure violence. He visualised a little cottage far away from the big towns, where at any moment frightening things could happen.

It should not be difficult. They had the guard Toulan to help them. The Tisons could easily be drugged. All he need do was walk out of the prison with confidence – for who should challenge him, who could suspect that the two municipaux were the Queen and Madame Elisabeth? Waiting outside the prison would be two carriages, and in the second of these he would be driven out of Paris.

And for that night’s work he was offered a lifetime of peaceful living in the country.

‘I will do it,’ said Lepître.

A great deal of money was needed for the enterprise, and Jarjayes found it difficult to raise it. It was necessary to wait awhile until he could sound those whom he could trust with the plan.

They needed forged passports. Lepître could provide these, but Lepître was nervous, and he was showing signs of strain.

Madame Tison noticed it. She said: ‘And what’s the matter with you? You look anxious this morning, Citizen.’

‘It’s my leg paining me,’ Lepître answered, indicating his lameness.

Madame Tison nodded grimly. ‘This is a different job from teaching a lot of children, eh?’

The ex-schoolmaster agreed that it was; he tried to talk of the old days, but all the time he was conscious of Madame Tison’s watching eyes. She was alert. There was no doubt of that. She hated royalty; she was a passionate exponent of equality, and her passion seemed to give her an extra sense. How could one be sure what she suspected?

The money was found at last, and passports were prepared. Lepître liked the feel of good money in his pockets. It was so simple really. The drugged snuff would not be so very difficult for him to administer. He would go into the Tisons’ room and, sitting over a bottle of wine with them, offer them his snuffbox; he would stay with them until they nodded and slipped off into unconsciousness. Everything would be ready, waiting. The General would come in, disguised as the illuminateur, and with him he would bring greasy smocks, trousers and floppy hats; the royal children would be hastily dressed in these garments; and Jarjayes would calmly lead them out of the prison to where the carriage was waiting. Meanwhile Lepître would arrive in the Queen’s cell with the garments for the Queen and Madame Elisabeth; and when they had donned them he would conduct them out of the prison. In less than an hour after that they would be driving out of Paris.

It was the day before that arranged for the escape. Lepître called on Madame Tison. ‘I must have a talk with you both to-morrow evening,’ he said. ‘Then your husband will be there, eh?’

‘Yes, if you wish it,’ said Madame Tison.

‘I’ll be along about dusk, I should think. See that he is here then, that I may talk to you both.’

The woman nodded.

‘Have a glass of wine now you’re here, Citizen,’ she said.

So he went into her room. It would be well to rehearse what should happen on the next day.

He would sit at her table as he was sitting now. He would drink a glass of wine, talk of what he had seen that day in the Place du Carrousel or the Place de la Revolution; he would talk about the prisoners.

‘Your wine is good, Madame Tison.’

She grunted: she was an ungracious woman.

‘All is well with your prisoners, I trust?’ he went on.

Again she grunted. ‘They make little trouble. How could they? We’re the masters now, eh, Citizen?’

‘We are the masters now,’ he said with the air of a good patriot. ‘Are the children playing with them now?’

‘The boy is in the courtyard, playing with that stick of his … prancing about, pretending it’s a horse and he’s riding it. A difference, eh, Citizen, from the old days! A stick now, instead of a horse all fitted up with gold and silver embroidery.’

‘A great difference. And the girl?’

‘Quiet she is … I don’t trust her … never did trust people who were too quiet.’

It seemed to Lepître that her eyes were boring into him. He found it difficult to repress a shiver.

He drew out his snuff-box. ‘You like a pinch of snuff, I understand.’

Her eyes gleamed. She was rapacious; she would never refuse anything; and Tison was the same. That was why they could be relied on to take the snuff.

This was exactly how it should happen to-morrow evening.

‘Why, you don’t keep the box still, Citizen.’

So she had noticed his shaking hands. He fancied there was a malicious look about her eyes.

She took a liberal pinch appreciatively.

‘Did you hear, Citizen Lepître,’ she said, still keeping her eyes on him, ‘how the émigrés are falling into our hands? It’s like swatting flies, they say. They’re trying all manner of means to get out of the country. It makes me laugh.’ Madame Tison rocked in her chair with amusement. ‘Trying to get over the frontier … and some of them have been managing it. Do you know how? Forged passports … There have been more people caught with forged passports these last weeks, Tison tells me, than during the last two years.’

‘F … forged passports!’ stammered Lepître.

‘Well, there’s no need for you to look alarmed. We’re catching them, Citizen. We’re catching them.’ The woman leaned towards him. ‘They tell me they recognise these forged passports at a glance. Then … they drag ’em out of their fancy carriages … and it’s to the lanterne without delay. I’ll take another pinch of snuff, Citizen Lepître. Why … what’s wrong? You got the ague? You’re shaking so.’

He stood up; his fear seemed to form a haze about him so that he could not see her clearly.

She knows, he thought. She has found out.

‘I’ll be getting to my own quarters, Citizeness,’ he said. ‘I feel a little dizzy. This leg of mine has been paining me and I’ve had one or two of my sick turns lately.’

‘I should go to your bed, Citizen; and I’d stay there for a day or so.’

He spent the night pacing up and down his room. He brought the uniforms of the municipal councillors from the chest in which he had hidden them. He felt so terrified that he could scarcely stand. Sweat poured down his face; he lay on his bed trembling.

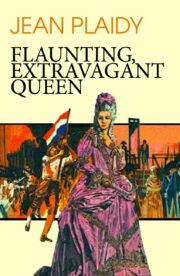

"Flaunting, Extravagant Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Flaunting, Extravagant Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Flaunting, Extravagant Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.