Fersen, who had planned every detail to perfection, failed to realise that the building of such a magnificent vehicle could not be kept entirely secret; and although his story was that it was for a Russian baroness, rumours soon started from the coachmaker’s workshop.

Provence and Josèphe were to leave the Tuileries at the same time, but Provence was arranging his own escape and proposed to travel to Montmédy by a different route; there they would meet.

Provence had different ideas from those of Fersen, and decided that he and Josèphe would travel in a shabby carriage without attendants.

The Queen was packing her jewels, in her apartment, preparing them for Monsieur Léonard to take into Brussels, when she became aware of Madame Rochereuil standing in the doorway, watching her.

Antoinette swung round, and with difficulty prevented herself from crying out.

‘Yes, Madame Rochereuil?’ she said coldly.

‘I wondered if I might help you, Madame, with the packing.’

The woman’s eyes were on the jewels spread out on the sofa.

The Queen said: ‘There is nothing you can do.’

Madame Rochereuil left her, but the Queen was anxious. She called Madame Elisabeth to her.

‘That woman is spying on us,’ she said. ‘That woman knows we plan to go.’

‘Could we not rid ourselves of her?’ asked Elisabeth.

‘That would be to call suspicion on us. I have discovered that Gouvion, a member of the Jacobin Club and a rabid revolutionary, is her lover. She watches all we do, and reports it to her Jacobin friends. Elisabeth, she knows!’

‘She cannot know when. No one knows when …’

‘But she will be spying on us. How can we ever leave as we planned? You know how careful we shall have to be … And she will be watching us all the time.’

And so it seemed, for at odd moments Madame Rochereuil would be near them, smiling quietly, alert, watchful, knowing herself to be recognised as a spy, the spy of whom they dare not rid themselves.

‘We cannot leave on the 6th,’ said Antoinette to Fersen. ‘The wretched woman, Rochereuil, knows we intend to go. She saw me packing my jewels. I told her that they were a present to my sister, but I could see she did not believe me.’

‘We must wait awhile,’ said Fersen uneasily.

It became clear that they were wise to do so, for shortly afterwards an article by Marat appeared in the Ami du Peuple. ‘There is a plot,’ he wrote, ‘to carry off the King. Are you imbeciles that you take no step to stop the flight of the royal family? Parisians, you stupid people, I am weary of telling you that you should have the King and Dauphin under lock and key; you should lock up the Austrian woman and the rest of the family. If they escaped it might mean the death of three million Frenchmen.’

Marat was afraid that, if the King escaped from Paris, he would gather forces together and there would be civil war throughout France.

‘We cannot go yet,’ it was decided in those secret meetings in the Tuileries. ‘We must wait until suspicions are lulled.’

Fersen fretted; so did Bouillé and the Duc de Choiseul. Everything had been arranged to the smallest detail. But Marat had aroused the suspicions of the people and Madame Rochereuil was watchful.

So during the days of that June it was necessary to infuse a listless air into the Tuileries. Never for one instant must they forget the watching eyes of Madame Rochereuil.

‘We must leave on the 19th,’ said Fersen desperately. ‘We dare not delay longer.’

So the escape was fixed for the 19th.

But on the evening of the 18th Madame de Tourzel came to the Queen and said: ‘Madame Rochereuil will not be in atendance on the 20th. She has asked leave to go and visit someone who is sick. I believe this to be true, because I heard from another source that Gouvion is unwell.’

‘This is a heaven-sent opportunity,’ cried the Queen. ‘We will leave on the 20th. Not on the 19th.’

It was late to make alterations, but she was sure that it would be folly to attempt to leave the Palace under the spy’s watchful eyes, when they could do so the next day in her absence. She called Monsieur Léonard to her and sent him off with the jewels. He would meet the cavalry on the road; and he was to tell their leader that the royal party would be twenty-four hours late.

Léonard left.

The 20th dawned. This was the day of escape.

The day seemed endless. Antoinette was certain that never before had she lived through such a long day. In the late morning, to the great relief of the Queen, Madame Rochereuil went. She was sure now that if they had been suspected of trying to escape earlier in the month, they were no longer; for if this had been so surely Madame Rochereuil would never have been allowed to leave her post.

Louis was as calm as ever. Louis was fortunate, as he never showed emotion.

Often during that long day Elisabeth and the Queen exchanged anxious glances, each aware of the other’s thoughts. Will the time never pass?

They stood at the windows, looking out. The sun was shining. That was fortunate; it was one of those lovely summer days which would draw the people out of the streets away to the open country.

Antoinette saw that Elisabeth’s lips were moving silently in prayer.

There was Mass to attend, and after that the family had their midday meal together. Antoinette was amazed that Louis could eat with his usual appetite. She had to force herself to appear normal, so did Elisabeth, and even Provence was more silent than usual. Antoinette was glad she had been able to keep their plans from the children.

She said to the King: ‘You are going to your apartment to rest? I shall go to mine, I think. I wish to work on my tapestry.’

She had not been in her room more than five minutes when a servant announced the arrival of Fersen. She received him in her apartment with only Elisabeth present.

‘The woman is not here?’ he asked.

‘No. She is having a short holiday.’

‘I wish she had taken it yesterday.’

‘Do not worry. You worry too much,’ said the Queen tenderly.

‘I am thinking of the soldiers waiting at their posts.’

‘But Monsieur Léonard can be trusted. He will reach them at the appointed time and tell them that we shall be twenty-four hours late.’

‘I would that I were driving you all the way.’

The Queen did not meet his eyes. ‘It is the King’s command,’ she said.

‘Is everything ready now?’ asked Fersen. He looked anxiously at the gilded clock on the wall. ‘Does it seem to you that time stands still?’

Antoinette nodded.

‘When I leave the Palace,’ he went on, ‘I shall take a look at the berline, to make sure everything is ready. I shall have the wine and food packed into it, and then it will be sent to wait for us beyond the Barrier. We shall then change vehicles, and away. You will not forget your parts.’

‘No,’ said the Queen. ‘I am the governess to my children, employed by Baroness de Korff – my dear Tourzel – the King is the lackey, and Elisabeth the companion; then dear Madame Neuville and Madame Brunier are servants, are they not? And that completes our little party.’

‘Is it necessary to take them? There seem so many of us,’ said Elisabeth.

‘I must have my maids,’ said the Queen. ‘I shall need them to help me with my toilet.’

‘They are trustworthy,’ said Fersen; ‘and they may leave an hour before you do, and can join the party later on. No one will stand in the way of their going. The difficulty will be to get you two ladies, the King and the children away without suspicion.’

‘I know,’ agreed the Queen.

‘Take care.’

He put out his hands, and Elisabeth did not look at them as for a moment they clung together.

Then Fersen was taking his leave.

When he had gone the Queen and Elisabeth took Madame Royale and the Dauphin for a drive in the Tivoli pleasure garden; when they returned the children went to bed and the King and Queen took supper with Elisabeth, Provence and Josèphe. After the meal they retired to the great drawing-room and, huddling together far from the doors, discussed the last-minute plans.

Every now and then they would glance at the clock and comment on the slow passage of time.

Privacy was never of long duration. The royal family must not excite suspicion by remaining too long in the private drawing-room. They made their way to the great salon where the members of the Court were gathered. Some talked; some were engaged in card games. The great test was beginning. There among those courtiers the impression must be given that this night was no different from countless others.

The King was calm, enough. He sat on his chair, looking sleepy, as he usually did during the evening. He was discussing the latest phase of the revolution in the way he discussed such things every night.

It was ten o’clock when the Queen rose and remarked that she wished to write a letter and would shortly return. With madly beating heart she slipped through the gloomy corridors to the children’s apartments. Madame de Tourzel was waiting for her.

‘You are ready?’ breathed the Queen.

‘Yes, Madame.’

Antoinette went to her daughter’s bed. Madame Royale opened her eyes and stared at her mother. ‘You are to get up quickly. Ask no questions. Dress at once. Madame de Tourzel will help you.’

Madame Royale obeyed instantly.

Antoinette went to the Dauphin’s bed.

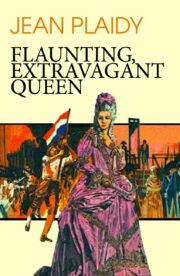

"Flaunting, Extravagant Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Flaunting, Extravagant Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Flaunting, Extravagant Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.