And to Maria Carolina they talked of the sadness of Antoinette, of the courage of Antoinette, and how they had good reason to love her.

Orléans made good use of his time in London.

A year or so after her imprisonment, Jeanne de Lamotte had escaped from the Salpêtrière. She had good reason to believe that the Duc d’Orléans might have had some hand in that escape. Clothes had been smuggled in to her and, with the kindly help of the guards and sentries who, it seemed, had been paid well to look the other way, she slipped out of her prison and made her way to the Seine where a boat was waiting to take her out of the city. She at length reached the frontier and journeyed through the Netherlands to London.

There she joined her husband. The sale of the diamonds had made them rich and, when it was discovered that she was that Jeanne de Lamotte-Valois who had played such a big part in the notorious case, she was welcome in several houses, for she had such amusing stories to tell of the Queen of France; and Jeanne told her stories, making them more and more outrageous with each telling; if ever she felt a little ashamed of her lies, she merely had to let her fingers touch the angry-looking V on her breast, and then she felt that nothing she could say would be too bad.

Now the Duc d’Orléans was seeking her out.

‘How would you like to return to France?’ he asked her.

‘Return to France!’ Jeanne firmly shook her head. ‘To the Salpêtrière?’

‘Certainly not to the Salpêtrière – to a house of your own where you could receive your friends.’

‘It would not be safe. I should not wish to suffer again what I have endured at the hands of those unjust rogues.’

‘You would not.’

‘But I escaped from prison, Monsieur le Duc. I was sentenced for life.’

‘Have you not heard, Madame, that the people have stormed the Bastille? Do you not know what they say now of Antoinette? No! You would run into no danger if you returned to Paris. I would give you an hôtel in the Place Vendôme.’

‘In exchange for what?’

The Duke took her by the chin and kissed her lightly.

‘All Paris would be interested in your little stories of Antoinette.’

Jeanne smiled.

‘There is no place like Paris,’ she said.

‘Then … return to your home. There is work for you to do.’

The Queen paced up and down her apartments.

‘Louis,’ she said, ‘how can we endure this life? We had a little respite at Saint-Cloud, and now we are back … back here in this dreary place. How much longer shall we remain prisoners here?’

Louis shook his head sadly.

‘We should seek help from outside,’ she cried. ‘There is my own country. Ah, if only Joseph were alive!’

Joseph had died recently, and her brother Leopold was now Emperor. Leopold had his own difficulties; they would not include fighting in his sister’s cause.

Antoinette’s plan was that the Austrian armies should march to the frontiers of France, and that Louis should muster as many men as he could and go to meet them; and that the might of Austria should show the French that Austria disapproved of the way in which they were treating their monarchs.

But there was no help coming from Austria.

Orléans had returned to Paris, and La Fayette was afraid to raise the matter of his exile, for fresh demonstrations were now occurring in the Palais Royal.

Moreover that criminal and jewel-thief, Madame de Lamotte, was now established in the Place Vendôme, and libel after libel poured out from her pen. There was a new story of the necklace – Madame de Lamotte’s version. No story was too vile to be attached to the Queen.

There was one man who was keeping the revolution at bay. This was Mirabeau. He was now using his considerable gifts to the limit and was serving both the National Assembly and the monarchy, deftly keeping the balance between them, working with his tremendous powers to weld the two together.

The King had offered to give him promissory notes to the value of a million livres, to be paid when Mirabeau had brought about that which he had set out to do. This was to bring the revolution to an end and place the King firmly on the throne. Mirabeau’s debts would be settled, and he would be left affluent. He was determined to earn the money and at the same time win for himself fame with posterity.

He could do it; he knew he could do it; he firmly believed that he held the fate of France in his hands.

Brilliantly he played his game. Eloquently he spoke in the National Assembly; he was working for the new constitution; and at the same time he intended to save the King and Queen. He was a master of words and rhetoric. He could sway the assembly, he could persuade the King.

Such brilliance was certain to bring him enemies. He was threatened with the cry ‘Mirabeau à la lanterne!’ But he snapped his fingers. Marat accused him of working with the enemy. He snapped his fingers at Marat.

His plan was to stop the violence of the revolution with greater violence, and he said to the King: ‘Four enemies are marching upon us: taxation, bankruptcy, the army and winter. We could prepare to tackle these enemies by guiding them. Civil war is not certain, but it might be expedient.’

He was like a giant possessed. Civil war! Law and order armed to fight the murderous mob!

The King was horrified. Was Mirabeau suggesting that he should fight against his dear people!

‘Oh, excellent but weak King!’ mourned Mirabeau. ‘Most unfortunate of Queens! Your vacillation has swept you into a terrible abyss. If you renounce my advice, or if it should fail, a funeral pall will cover this realm; but should I escape the general shipwreck, I shall be able to say to myself with pride: I exposed myself to danger in the hope of saving them, but they did not want to be saved.’

Realising the danger which threatened the King and Queen in Paris, he consulted with Fersen, for he saw that the Swede’s plan to get them out of Paris was a good one.

Rouen would be useless now; they must go farther towards the frontier, where the Marquis de Bouillé was near Metz with his loyal troops.

Fersen made the journey to Metz and returned with the news that the King and Queen should leave Paris without delay, for Bouillé was not so sure of the loyalty of his troops as he had once been and he feared that disaffection was spreading.

Still the King hesitated.

‘Then,’ cried Mirabeau, ‘must Your Majesty come out of retirement. You must show yourself in the streets. The people do not hate you. Have you not seen that, though they shout against you, when you appear they call you their little father? They have always had an affection for you. Are you not Papa Louis? But you shut yourself away, while your enemies spread evil tales concerning you.’

Fersen was terrified of the Queen’s appearing in the streets, but Mirabeau was impatient.

This was not the time to hesitate. It seemed to him that nobody but himself realised all that was at stake.

He, Mirabeau, could save France; he, Mirabeau, would be remembered in the generations to come as the man who had averted the destruction of the monarchy; the man who had saved his country from anarchy.

It was Mirabeau who had stood beside Orléans and helped to raise the storm; it should be Mirabeau who cried: ‘Be still!’ and for whom the rising tide of bloodshed should be called to halt.

But he could get no help. The King would not countenance a civil war; he would not show himself to his people; he would not escape.

So Mirabeau continued deftly to keep his balance. He swayed the Assembly and he worked for the monarchy.

‘Mirabeau is shaping the affairs of France,’ said Marat, said Danton, said Robespierre; and said Orléans.

And one day, when his servant went to call Mirabeau, he found that his master was dead.

Mirabeau had suffered from many ailments, which were largely due to the life he had led. Was it the colic which had carried him off, or that kidney trouble which had afflicted him?

‘Death from natural causes,’ was the verdict.

But many people believed that the Orléans faction had determined to put an end to the man who had once been their friend and was now working to destroy all that they hoped for.

There were many in the streets to whisper of Mirabeau’s sudden death: ‘Oh, a little something in his wine. He lived dangerously, this Mirabeau. He thought he was the greatest man in France. Then death came, silent and swift.’

In the Tuileries fear descended. The King and the Queen now realised how much they had depended on Mirabeau.

Chapter XIII

ESCAPE TO VARENNES

The death of Mirabeau greatly increased the danger to the royal family. In the Palais Royal men and women were demanding action. This was at the instigation of the Jacobins – members of that Club des Jacobins which the Club Breton had become. Club Breton had been the first of the revolutionary clubs, and many of its members were Freemasons or members of secret societies. It consisted mainly of partisans of Orléans – who was very much under the influence of Freemasonry – and the name of the club had been changed when it set up its Paris headquarters in the convent situated in the rue Saint-Honoré, for the headquarters of the convent which they had taken over was in the rue Saint-Jacques.

The purpose of the Jacobins was to press on with the revolution.

Soon after the death of Mirabeau, the King and Queen, feeling the need of a change, decided that they would go to Saint-Cloud for Easter. Their plans soon became known to the Jacobins, as one of the Queen’s women, Madame Rochereuil, had a lover, a member of the Club, and he had assured her that the way in which she must serve her country – or herself be suspected of treachery – was to spy on the Queen.

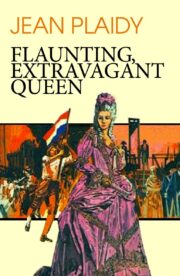

"Flaunting, Extravagant Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Flaunting, Extravagant Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Flaunting, Extravagant Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.