The jewellers, in desperate need of the money, immediately agreed to reduce the price of the necklace, so that there was no delay on account of the argument which Jeanne had hoped for.

She then went to the Cardinal and told him that the Queen could not raise the money, but wished him to arrange with the jewellers that there should be a double payment on the 1st October instead of the first being paid on the 1st August.

The Cardinal was alarmed. Jeanne began to see great cracks in her scheme. She had planned from move to move; and now she saw only one left to her.

She went to the jewellers.

‘Monsieur Boehmer,’ she said, ‘I am worried. I have reason to believe that the Queen’s signature on the contract may have been forged.’

Boehmer was pale with terror; he began to tremble.

‘What shall I do?’ wailed the jeweller. ‘What can I do?’

Jeanne said almost blithely: ‘You must go to the Cardinal. He will look into this matter, and if he finds there has been fraud … well, the Cardinal will never allow it to be said that he has been the victim of such a disgraceful fraud. Have no fear, Monsieur Boehmer. The Cardinal will pay you your money.’

Jeanne thought that she had slipped gracefully out of the difficulty. She had the château she had bought at Bar-sur-Aube; so she retired to the country.

There she would stay for a while; then perhaps she would join her husband in London where he was disposing of the diamonds.

But the jeweller did not go to the Cardinal. Instead he went to Madame de Campan and through her reached the Queen.

Jeanne was dining in state in her country home when a messenger arrived at her château.

‘Madame,’ he cried, ‘Monsieur le Cardinal de Rohan was arrested at Versailles this day.’

Jeanne was alarmed. It seemed to her that for the first time luck had gone against her.

She retired hastily to her bedroom where she burned all the letters which the Cardinal had sent to her regarding the transaction.

She felt better after that.

She went to bed and tried to compose herself; she was already making plans to join her husband in London. It would be safer to be out of the country for a spell.

At five o’clock in the morning there was a disturbance in the courtyard. She rose and threw a robe about herself. Her maid came hurrying to her.

‘They come from Paris,’ she stammered.

‘Who?’ demanded Jeanne.

But they were already on the staircase. They marched straight to her bedroom.

‘Jeanne de Lamotte,’ they cried, ‘you are under arrest.’

‘By whose orders, and on what charge?’

‘On the order of the King, and for being concerned in the theft of a diamond necklace.’

In the Queen’s theatre was played that delightful comedy, Le Barbier de Seville – the Queen playing Rosine enchantingly, looking exquisite, tripping daintily across the stage in a delightful gown made for the occasion by Madame Bertin at great cost. Vaudreuil played Almaviva with great verve; and Artois strutted across the stage, an amusing Figaro: ‘Ah, who knows if the world is going to last three weeks!’

The glittering audience applauded, but between the acts they were saying to one another: ‘What does this mean – this matter of the necklace? Is it true that the Cardinal was the Queen’s lover? There must be a trial, must there not? Then who knows what we shall hear!’

They were certain that what they heard would be of greater interest than the play they had come to Trianon to watch.

In Bellevue where, under Adelaide, those older disgruntled members of the nobility gathered, they talked of the latest scandal. ‘What this matter will reveal I would not like to prophesy,’ declared Adelaide, looking sternly at Victoire. (Sophie had died some years before.) Victoire knew what she was prophesying and that she would be greatly disappointed if it did not come to pass.

In the Luxembourg, Provence’s friends gathered about him. They confessed themselves astonished with this newest scandal, and they asked one another how the children of such a woman could possibly become good Kings of France. For one thing, how could it be certain that they had any right to be Kings of France?

In the cafés of the Palais Royal, men and women were thronging in greater numbers than ever before. A diamond necklace, they murmured. 1,600,000 livres spent on one ornament while many in France starved. Their hero, Duc d’Orléans (Chartres had assumed the title on the recent death of his father) went among them, his eyes gleaming with ambition. ‘This cannot go on,’ murmured the people. ‘It cannot go on,’ echoed Orléans. ‘And when it is stopped … what then?’

And throughout the Rohan family and its connections there were many hurried conferences. A member of their family was in danger. They must all rally to his side. Connected with the Rohans were the houses of Guémenée, Soubise, Condé and Conti, some of whom declared they had already been slighted by the Queen.

They would all stand together; and they determined that all blame should be shifted from the shoulders of their relative. And the best way of doing this was to place it on those of a more eminent person.

So, as the affair of the necklace became the topic of the times, the Queen’s enemies began to mass on all sides.

Antoinette lay on her bed. She was pregnant and in two months’ time was expecting the birth of a child. She had had the curtains drawn about her bed because she wanted to shut out reminders of that tension which she sensed all about her.

Everyone in the Palace, everyone in Versailles and Paris was eagerly awaiting the verdict in the necklace trial.

She had heard that all day the people had been crowding into Paris, that every important member of the Rohan family and its connexions had come to the Capital. They paraded the streets of the city dressed in deep mourning, all their servants similarly clad; they were clad in mourning on account of their innocent relative. It was preposterous, they implied, that a noble Prince, a Rohan, should be made a prisoner merely because he had been selected as a shield behind which the lascivious, acquisitive and wicked Austrian woman might cower.

‘Why must they go on and on about this matter?’ Antoinette had asked Louis wearily. ‘The necklace is stolen, the stones have been broken up and sold. That should be an end to the matter. Why not let it rest?’

‘Your honour is at stake,’ said the King sadly. ‘We must defend it.’

‘Do they think that I stole the necklace?’

‘They will think anything until we convince them to the contrary.’

Then she had thrown back her head and declared: ‘Well, if they want this thing made public, so let it be. Let us have this matter tried by the Parlement. Then my complete innocence will be proved, and all France must acknowledge it.’

So on this May day, nine months after the arrest of the Cardinal, the case of the Diamond Necklace was being tried by the Parlement of Paris.

The judges had entered the great hall of the Palais de Justice. The crowds who had gathered in the square cheered them as they went in. The streets, the river banks, the taverns and cafés were full; all who could had come to Paris on this May day that they might immediately hear the verdict on the most notorious case of the age.

Among the prisoners was the fabulous Comte de Cagliostro, for Jeanne’s quick mind had searched about her for someone on whom she could fix the blame. She remembered an occasion when she had walked in the gardens of the Cardinal’s palace with Cagliostro, and she made herself believe that the Count had put the idea of fraud into her head. She therefore accused him of the theft, and as a result he was arrested.

Now, in alliance with the mighty members of the Rohan family were the Freemasons, one of the most powerful societies in France and throughout the world. Cagliostro was Master of a lodge, one of the leading men of the movement, and it was inconceivable that the mighty Cagliostro should be treated as a criminal.

There were two minor prisoners involved – Rétaux the forger and Oliva the modiste prostitute. Jeanne’s husband had, fortunately for him, been in England when the arrests were made, and there he stayed and the diamonds with him.

This meant that the diamonds could not be produced, and the rumour which found most favour was that the Queen had been behind the whole thing, that the Cardinal had destroyed her letters to him out of gallantry, and that the Queen kept the necklace in a secret jewel box.

Trembling before the judges the little Oliva told of her meeting with the Cardinal in the Grove of Venus. The Cardinal told how he had been duped, and as he spoke he kept his eyes on the commanding figure of Cagliostro, seeming to draw as much strength from him as he did from his assembled relations who, dressed in mourning which they had been wearing ever since the arrest of this member of their family, presented a formidable company.

The sixty-four judges and members of the Parlement knew that they were expected to declare the Cardinal and Cagliostro innocent; they were also aware that they were dealing with more than a case of theft. The verdict they would give would be more than one of guilty or not guilty; it might be an indictment of the monarchy, for Joly de Fleury, in the name of the King, had made it clear that even if the Cardinal were acquitted as a dupe in the affair, he had been guilty of ‘Criminal presumption’ in imagining that the Queen would meet him in the gardens of Versailles. Unless a verdict of Guilty was given, the Queen must surely be exposed as a woman of light reputation, since a Cardinal who was also a Prince could imagine she would meet him thus; and on this incident was based the whole structure of the case.

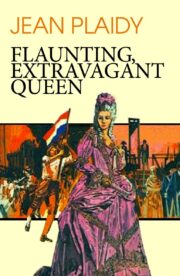

"Flaunting, Extravagant Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Flaunting, Extravagant Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Flaunting, Extravagant Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.