Antoinette’s thoughts were wandering. They had come to rest in the gardens of the Petit Trianon. What fun to collect plants from all over the world and replant them in her gardens! She would have all the rarest shrubs – magnolias … and trees from India and Africa. It would be gratifying to see the delight of the people who wandered there on Sunday afternoons, and with them would be little children, the dear little children, peeping out from their mothers’ skirts to catch a glimpse of the Queen.

Louis had stopped speaking and was thinking of Abbé Robert Jacques Turgot who had already attracted attention by the manner in which he had opposed the Abbé Terray’s taxation. The man was already known throughout France as a reformer. He had set up in distressed areas those ateliers de charité to aid the starving people; he had built roads and his reforms had made of Limoges, his native town, one of the most advanced areas of France. The King had been drawn to him, not only because their ideas were in accord, but because he was shy, even as Louis was shy, because he walked awkwardly and was generally gauche.

‘Turgot already has a programme prepared,’ stated the King. ‘He sees as through my eyes. He is determined to help me make the people happy. He says there shall be no bankruptcy, yet no increase in taxation. I am delighted with his ideas. I am certain that together we can put right much that is wrong.’

‘It will surely be so,’ said Antoinette dutifully.

‘We ourselves,’ Louis explained, ‘must set an example. It will not do for us to be extravagant while we try to enforce reforms.’

‘That is quite true,’ murmured Antoinette.

‘I have decided to cut down on my personal expenses,’ Louis told her. ‘I told La Ferté, when he came to me asking for orders because he was the Comptroller of my Menus Plaisirs, that I should no longer need him, for my Menus Plaisirs are to walk in the park, and that I can control those myself.’

‘That is the way to please the people,’ cried Antoinette. ‘I will tell them that I no longer need that money which is called the droit de ceinture. Ceintures are no longer worn, therefore I have no need of it.’

‘The people shall be told of that bon mot,’ said the King with a smile. ‘It will amuse them, and it will show how eager we are to do what is right.’

‘Louis, you are happy, are you not? You are not so much afraid of being King as you thought you might be?’

She had moved closer to him, and she saw that he was startled. He feared, she knew, that she was about to reopen the dread subject.

Antoinette knew that she could not persuade Louis to employ Choiseul. She was discovering that her husband was a stubborn man. But at the same time she remembered all the humiliation she had been forced to endure at the hands of Madame du Barry, and she was determined that the Duc d’Aiguillon, the protégé and friend of the du Barry, should not retain his position at Court.

Maurepas, the new Minister without Portfolio and President of the Council, while realising that the King was determined not to be governed by his Queen, sensed also that the Queen was too frivolous to be likely to do this; at the same time he remembered her obstinacy over the du Barry incident, and he was eager not to upset her.

He therefore decided to throw out the Duc d’Aiguillon in order to placate the Queen and show her that he was her friend. All those who had supported d’Aiguillon blamed the Queen and determined to do everything in their power to undermine her growing popularity.

They had the aunts and Antoinette’s sisters-in-law to help them in this. They had suspected that Provence’s ambition would bring him to their side, although Provence was clever enough to hide his animosity.

It seemed then, to those who wished the Queen ill, that it would not be difficult to work up a strong faction against her.

This became apparent in a very short time.

Since her accession Antoinette’s immediate circle had enjoyed a relaxation of the usual strict etiquette in the intimacy of her company. They relished this the more because it was a novelty.

‘I suffered from a surfeit of “You must do this … you must do that”,’ she told them. ‘Depend upon it, my dears, I shall not impose those rigours on you, for if I do you will hate me, and I want you to love me.’

The ladies crowded round her and kissed her cheek, instead of her hand. ‘As though anyone could hate Your Majesty!’ they cried.

The Marquise de Clermont-Tonnerre, the youngest of all her ladies and something of a tomboy, picked up a coif and put it on her head, pulled a solemn face and cried in accents very like those of the banished Madame de Noailles: ‘Your Majesty must not allow your ladies to kiss your cheek. No … Your Majesty’s hands are for kissing … not your cheeks!’

‘Be silent! Be silent …’ warned the more sober ladies.

But Antoinette only laughed. ‘You imitate her very well,’ she said. ‘We shall give you a part in the theatricals, my dear.’

‘So we are to have theatricals?’

Antoinette had not thought of them until that moment. Now she decided they would perform a play for the benefit of the Court, and she herself would take the principal part.

‘The Court will disapprove heartily,’ she was told. ‘A Queen to play a part! Versailles will stick its head in the air and declare it does not know what the Court is coming to.’

‘Versailles will do what it likes. We shall give our play at Muette … or perhaps at my dear Petit Trianon. But play we shall.’

The daring little Marquise took the Queen’s hand and, kneeling ceremoniously, held it to her lips.

They all laughed together; and the ladies told each other afterwards that there had never been such an adorable and affectionate Queen of France as Her dearest Majesty.

Then came that day when she must receive certain dowager ladies who had called to condole with her on the loss of her grandfather, and to congratulate her on her accession to the throne.

Her ladies were laughing as usual while they helped her dress in the sombre mourning which the occasion warranted.

‘Now we must remember,’ she admonished them, ‘that this is a very solemn occasion, and these old ladies will doubtless expect me to weep. So do try to compose yourself, my dears.’

‘Oh, yes, Your Majesty,’ they chorused.

Antoinette tapped the cheek of the little Marquise. ‘You especially,’ she said. ‘Curb your high spirits until the departure of the dowagers.’

The Marquise smiled charmingly; two dimples appeared in her cheeks. She was such a delightful creature that the Queen’s smile deepened. It was such a pleasure to choose those she would have about her.

Then began the ritual. It was as formal as any ceremony in the previous reign. Each of the ladies must approach the Queen, fall to her knees, remain there precisely to the required second, must rise and wait for the word from the Queen before she began to speak; and then the Queen must chat with each for a certain time, which must be neither more nor less than the time she chatted with any of the others.

So they came – dreary old ladies in their mourning coifs, looking, thought Antoinette, like a flock of crows, like a procession of gloomy beguines.

She was weary of them. Her fingers impatiently fumbled with her fan.

About her her ladies had ranged themselves, the little Marquise de Clermont-Tonnerre immediately behind her so that she was completely hidden by the Queen’s dress with its panniers which spread out on either side of her.

Then, as she was talking to one of the elderly ladies, Antoinette heard a giggle behind her.

That bad child, she thought. What is she doing now to make them laugh? It was as much as Antoinette could do to suppress a smile; and to smile, she knew, would cause grave offence on this occasion when she was receiving condolences for the death of the King.

‘Madame,’ she was saying, ‘I thank you from the bottom of my heart. This is indeed a time of deep sorrow for our family. But the King and I pray each day that God will guide us in the way we should go for the glory of France…. ’

She felt a movement at her feet and, glancing down, she saw the little Marquise hidden from the old dowager by the panniers of her – Antoinette’s – dress, sitting on the floor, peeping up at her, pulling her face into such a contortion that, in spite of its round and babyish look, she bore some resemblance to the lady who stood before the Queen.

It was too late to check the sudden smile which came to Antoinette’s lips. She hastily lifted her fan; but there were too many people watching her. Josèphe had seen. Thérèse had seen.

Almost immediately she collected herself; she went on with her speech; but for a Queen – and Queen of France – to laugh in the middle of a speech of thanks for the condolences of an honoured subject was so shocking that her enemies would not allow it to be passed over lightly.

Josèphe and Thérèse went as fast as they could to confer with the aunts. The aunts made sure that the story was circulated in those quarters where it would do most harm.

Provence seized on it. If at any time it should be necessary to prove the lightness of Antoinette such incidents as these should be remembered. Moreover they should be stressed at the time they happened; it would make them all the more effective if it should be necessary to resuscitate them.

The Duc d’Aiguillon’s party saw that it was repeated and exaggerated not only in the Court but throughout the whole of Paris.

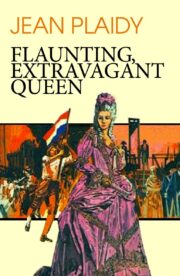

"Flaunting, Extravagant Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Flaunting, Extravagant Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Flaunting, Extravagant Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.