Ormskirk made a deprecating gesture. “But so abrupt, my dear Ravenscar! I am walking with you as a gesture of the purest friendliness!”

Mr Ravenscar laughed. “Your obliged servant, my lord!”

“Not at all,” murmured his lordship. “I was about to suggest to you—in proof of my friendly intentions, be it understood—that the removal of your—ah—impetuous young cousin would be timely. I am sure you understand me.”

“I do,” replied Ravenscar rather grimly.

“Now, don’t, I beg of you, take me amiss!” implored his lordship. “I am reasonably certain that your visit to Lady Bellingham’s hospitable house was made with just that intention. You have all my sympathy; indeed, it would be quite shocking to see a promising young gentleman so lamentably thrown away! For myself, I shall make no attempt to conceal from you, my dear fellow, that I find your cousin a trifle de trop.”

Mr Ravenscar nodded. “What’s the woman to you, Ormskirk?” he asked abruptly.

“Shall we say that I cherish not altogether unfounded hopes?” suggested his lordship blandly.

“Accept my best wishes for your success.”

“Thank you, Ravenscar, thank you! I felt sure that we should see eye to eye on this, if upon no other subject. I should be extremely reluctant, I give you my word, to be obliged to remove from my path so callow an obstacle.”

“I can understand that,” said Mr Ravenscar, a somewhat unpleasant note entering his level voice. “Let me make myself plain, Ormskirk! You might have my cousin whipped with my good will, if that would serve either of our ends, but when you call him out you will have run your course! There are no lengths to which I will not go to bring you to utter ruin. Believe me, for I was never more serious in my life!”

There was a short silence. Both men had come to a standstill, and were facing each other. There was not light enough for Mr Ravenscar to be able to read his lordship’s face, but he thought that that slim figure stiffened under its shrouding cloak. Then Ormskirk broke the silence with a soft laugh. “But, my dear Ravenscar!” he protested. “One would say that you were trying to force a quarrel on to me!”

“If you choose to read it so, my lord-?”

“No, no!” said his lordship gently. “That would not serve either of our ends, my dear fellow. I fear you are a fire-eater. Now, I am quite the mildest of creatures, I do assure you! Let us have done with this—I fear we shall have to call it bickering! We are agreed that we both desire the same end. Are you, I wonder, aware that your impulsive cousin has offered the lady in question matrimony?”

“I am. That is why I came to see the charmer for myself.”

Lord Ormskirk sighed. “You have the mot juste, my dear Ravenscar, as always. Enchanting, is she not? There is—you will have noticed—a freshness, excessively grateful to a jaded palate.”

“She will do very well for the role you design for her,” said Mr Ravenscar, with a curl of his lip.

“Precisely. But these young men have such romantic notions! And marriage, you will allow, is a bait, Ravenscar. One cannot deny that it is a bait!”

“Especially when it carries with it a title and a fortune,” agreed Ravenscar dryly.

“I felt sure we should understand one another tolerably well,” said his lordship. “I am persuaded that the affair can be adjusted to our mutual satisfaction. Had the pretty creature’s affections been engaged it would have been another matter. There would, I suppose, have been nothing left for me to do than to retire from the lists—ah—discomfited! One has one’s pride: it is inconvenient, but one has one’s pride. But this, I fancy, is by no means the case.”

“Good God, there’s no love there!” Ravenscar said scornfully. “There is a deal of ambition, I will grant.”

“And who shall blame her?” said his lordship affably. “I feel for her in this dilemma. What a pity it is that I am not young, and single, and a fool! I was once both young and single, but never, to the best of my recollection, a fool.”

“Adrian is all three,” said Mr Ravenscar, not mincing matters. “I, on the other hand, am single, but neither young nor a fool. For which reason, Ormskirk, I do not propose either to discuss the matter with my cousin, or to attempt to remove him from the lady’s vicinity. The rantings of a youth in the throes of his first love-affair are wholly without the power of interesting me, and although I do not pique myself upon my imagination, it is sufficiently acute to enable me to picture the result of any well-meant interference on my part.

The coup de grace must be delivered by Miss Grantham herself.”

“Admirable!” murmured his lordship. “I am struck by the similitude of our ideas, Ravenscar. You must not suppose that this had not already occurred to me. Now, to be plain with you, I regard your entrance upon our little stage as providential—positively providential! It will, I trust, relieve me of the necessity of resorting to the use of a distasteful weapon. Instinct prompts me to believe that you have formed the intention of offering the divine Deborah money to relinquish her pretensions to the hand of your cousin.”

“Judging from the style of the establishment, her notions of an adequate recompense are not likely to jump with mine,” said Mr Ravenscar.

“But appearances are so often deceptive,” said his lordship sweetly. “The aunt—an admirable woman, of course!—is not, alas, blessed with those qualities which distinguish other ladies in the same profession. Her ideas, which are charmingly lavish, preclude the possibility of the house’s being run at a profit, in the vulgar phrase. In a word, my dear Ravenscar, her ladyship is badly dipped.”

“No doubt you are in a position to know?” said Mr Ravenscar.

“None better,” replied Ormskirk. “I hold a mortgage or the house, you see. And in one of those moments of generosity, with which you are doubtless familiar, I—ah—acquired some of the more pressing of her ladyship’s debts.”

“That,” said Mr Ravenscar, “is not a form of generosity with which I have ever yet been afflicted.”

“I regarded it in the light of an investment,” explained his lordship. “Speculative, of course, but not, I thought, without promise of a rich return.”

“If you hold bills of Lady Bellingham’s, you don’t appear to me to stand in need of any assistance from me,” said Mr Ravenscar bluntly. “Use ’em!”

A note of pain crept into his lordship’s smooth voice. “My dear fellow! I fear we are no longer seeing eye to eye Consider, if you please, for an instant! You will appreciate, am sure, the vast difference that lies between the surrender: from—shall we say gratitude?—and the surrender to—we shall be obliged to say force majeure.”

“In either event you stand in the position of a scoundrel,” retorted Mr Ravenscar. “I prefer the more direct approach.”

“But one is, unhappily for oneself, a gentleman,” Ormskirk pointed out. “It is unfortunate, and occasionally tiresome, but one is bound to remember that one is a gentleman.”

“Let me understand you, Ormskirk!” said Mr Ravenscar. “Your sense of honour being too nice to permit of your holding the girl’s debts over her by way of threat, or bribe, or what you will, it yet appears to you expedient that someone else—myself, for example—should turn the thumbscrew for you?”

Lord Ormskirk walked on several paces beside Mr Ravenscar before replying austerely: “I have frequently deplored a tendency in these days to employ in polite conversation a certain crudity, a violence, which is offensive to persons of my generation. You, Ravenscar, prefer the fists to the sword. With me it is otherwise. Believe me, it is always a mistake to put too much into words.”

“It doesn’t sound well in plain English, does it?” retorted Ravenscar. “Let me set your mind at rest! My cousin will not marry Miss Grantham.”

His lordship sighed. “I feel sure I can rely on you, my dear fellow. There is positively no need for us to pursue the subject further. So you played a hand or two at piquet with the divine Deborah! They tell me your skill at the game is remarkable. But you play at Brooks’s, I fancy. Such a mausoleum! I wonder you will go there. You must do me the honour of dining at my house one evening, and of giving me the opportunity to test your skill. I am considered not inexpert myself, you know.”

They had reached Grosvenor Square by this time, where his lordship’s house was also situated. Outside it, Ormskirk halted, and said pensively: “By the way, my dear Ravenscar, did you know that Filey has acquired the prettiest pair of blood-chestnuts it has ever been my lot to clap eyes on?”

“No,” said Mr Ravenscar indifferently. “I supposed him to have bought a better pair than he set up against my greys six months ago.”

“What admirable sang-froid you have!” remarked his lordship. “I find it delightful, quite delightful! So you actually backed yourself to win without having seen the pair you were to be matched with!”

“I know nothing of Filey’s horses,” Ravenscar responded. “It was quite enough to have driven against him once, however, to know him for a damnably cow-handed driver.”

His lordship laughed gently. “Almost you persuade me to bet on you, my dear Ravenscar! I recall that your father was a notable whip.”

“He was, wasn’t he?” said Mr Ravenscar. “If Filey’s pair are all you say, you will no doubt be offered very good odds.” He raised his hat as he spoke, nodded a brief farewell, and passed on towards his own house, at the other end of the square.

He was finishing his breakfast, several hours later, when Lord Mablethorpe was announced. Coffee, small-ale, the remains of a sirloin, and a ham still stood upon the table, and bore mute witness to the fact that Mr Ravenscar was a good trencherman. Lord Mablethorpe, who was looking a trifle heavy-eyed, grimaced at the array, and said: “How you can, Max-! And you ate supper at one o’clock!”

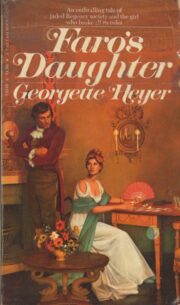

"Faro’s Daughter" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Faro’s Daughter". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Faro’s Daughter" друзьям в соцсетях.