“Oh my dear Max!” said Mrs Ravenscar, in a weak voice. “I ought to have suspected when she said she had the headache that she was planning some mischief!”

“Of course you ought!” replied Ravenscar. “Out, is she?”

“Her bed has not been slept in!” announced Mrs Ravenscar dramatically. “I went in, just to see how she did, a couple of hours ago, for you must know that I myself am quite unable to sleep in all the racket of town—not that I mean to complain, I am sure, but so it is! And she was not in her room, and not a word can I get out of that wicked maid of hers, who, I am positive, is in the plot! She will do nothing but cry, and say that she knows nothing!”

“You had better get rid of the girl,” said Ravenscar unemotionally.

“It is all very well for you to dismiss the matter so lightly, Max, but if you knew the number of abigails I have engaged to wait on Arabella, and each one of them less fit to be trusted than the last! Besides, how will that help us in our present predicament?”

“It won’t,” he replied. “Nor will anything help us in any future predicaments of the same nature except your forgetting all these megrims of yours, Olivia, and taking Belle to the balls and masquerades her heart craves for. Where has she gone tonight?”

“How should I know? I do not know how you can stand there, speaking to me in that brutal fashion, when you know how the least thing oversets my poor nerves! It is unfeeling of you, and I did not look for such usage at your hands, though to be sure I might well, for your father was just such another! I will tell you what it is, Max: if you had the smallest consideration for me, or for your poor sister—who is your ward, let me remind you!—you would have married years ago, and provided the child with a chaperon who might have escorted her to parties without being prostrated by exhaustion for days after!”

“Of all the reasons I ever heard for embarking on the married state, that one appeals the least to me!” said Ravenscar roundly. “You had better go up to bed, ma’am: I have little doubt that already your nerves will suffer from the effects of this night.”

“I have had the most dreadful palpitations this past hour and more. But where can that dreadful child be?”

“I have no idea, and nothing is farther from my intention than to scour London in search of her. She will return presently.”

“If anyone were to hear of these pranks of hers, it would ruin all her chances of making a good match!” mourned Mrs Ravenscar, drifting towards the stairs.

“Nonsense!” said Ravenscar. “Nothing can ruin the chances of an heiress of making a good match!”

Mrs Ravenscar said that she hoped he would be found to know what he was talking about, but that for her part she wished the child were safely married, so that she herself might retire to the peace of Bath. She then went upstairs, leaning heavily on the banister-rail, and, after swallowing some laudanum-drops, and soaking her handkerchief in lavender water, very soon fell asleep.

Miss Ravenscar, knocking softly on the door an hour later, was disconcerted at being admitted, not by her faithful abigail, as had been arranged, but by an exasperated half-brother. “Oh!” she exclaimed, letting fall her reticule. “W-what a start you gave me, Max, to be sure!”

“Who,” demanded Ravenscar, “is your cavalier?”

“He has gone,” said Arabella hastily, seeing that he was about to step out into the porch.

“Just as well for him!” said Ravenscar. “You are a cursed nuisance, Arabella! Where have you been?”

“Only to the masquerade at Ranelagh,” replied Arabella, in cajoling accents. “I did want so much to go, and Mama would not take me, and you said it was not good ton, so what was I to do?”

“Stay at home,” said Ravenscar uncompromisingly. “If you don’t take care, Belle, I’ll send you down to Chamfreys with a devilish strict governess to watch over you!”

“I’d run away,” responded Arabella, unperturbed by this threat, and slipping a small, coaxing hand in his arm. “Don’t be cross with me, dearest Max! It was such an adventure! And I did not once take off my mask, so no one will ever know.”

“Who took you there?”

“Well, I think I won’t tell you that, because ten to one you do not know him, and if you do you would say something disagreeable to him,” said Arabella. “But I will tell you one thing, Max!”

“I suppose I should be grateful! What is it?”

“Why, only that I remembered what you said to me today and you were quite right! At least, I am very nearly sure that you are, but I shall know more certainly in a day or two, I dare say.”

He looked down at her with misgiving. “What mischief are you brewing? Come, out with it, Belle!”

Her eyes danced. “No, I shan’t tell you! You would spoil it all. I think someone is trying to impose upon me, though I am not quite sure yet. It is the most enchanting sport!”

“Oh, my God!” said Ravenscar.

She pinched his arm. “Now don’t, I implore you, Max, put on that fusty face! I promise you I shall not do anything you would not like. And if you are sensible, and don’t let Mama plague me, I shall very likely tell you all about it presently.”

“I suppose you imagine that I like your running off to public masquerade with an adventurer?” said her brother caustically.

“Well, you should have taken me to it yourself, so it is qui your own fault,” said Arabella, dismissing the matter.

“Go up to bed, you baggage,” commanded Ravenscar, never proof against his half-sister’s wiles. “I wish to God I had never been saddled with the care of you! Let me tell you that when you do get married your husband will very likely beat you!”

Miss Ravenscar paused on the staircase, and looked bad the picture of mischief. “Oh, if that were to happen, I should fly back to my dear, kind, fusty, respectable brother!” she promised, and fled.

She bore her mother’s gentle complaints, when she met her later in the morning, with docility but not much sign of penitence. Except for warning her that if she again played truant, unseasonable hours he should send her into the country, her brother paid no further attention to her escapade. She was relieved, for she had quite expected him to probe a good deal deeper into the matter, and felt some surprise at his forebearance. She thought, peeping at him over the coffee-pot at the breakfast-table, that he looked preoccupied, but she would have been more than surprised had she known the cause of the faint frown between his brows.

Mr Ravenscar, if the truth were told, was toying with the idea of driving down to Berkshire, to pay a flying visit to his friend Waring. Twice he was on the point of ordering his curricle to be brought round to the door, and twice he refrained. “Damn it all!” he told the bell-pull, “I’m not going to spy on the boy!”

He compromised by calling in St James’s Square that evening. The rooms were rather thin of company, and the want of Miss Grantham’s presence was generally felt. Several dowagers were there, looking remarkably like birds of prey; and Lady Bellingham, who had started the evening by routing Sir James Filey, seemed to be in a belligerent mood. Sir James had go nothing out of her but a selection of home-truths which had made him fling out of the house in a rage; and, emboldened by this victory, she was able to face Mr Ravenscar with scarcely a tremor. He arrived only a few minutes before supper, and begged the honour of taking her down to it. This made her ladyship look a little wary, but she accepted his proffered arm, and descended the broad staircase with him in tolerable composure. He found a seat for her in the supper-room, supplied her with some lobster patties, and a glass of iced champagne-punch, and sat down opposite to her.

Lady Bellingham summoned up her courage, and said: “I am glad to have the opportunity of speaking to you, Mr Ravenscar. I do not know what my niece may have written to you on the subject of those horrid bills, but for my part I am very grateful to you for restoring them to me.”

“Pray do not give the matter a thought, ma’am! How long does Miss Grantham expect to be out of town?”

“As to that, I do not precisely know,” replied her ladyship vaguely. “She has gone to stay with friends, and there is no knowing how long they may persuade her to remain with them.”

“In what part of the country is she staying, I wonder?”

“Oh, I don’t—that is to say, not very far away! I don’t suppose you would know the place,” said her ladyship firmly. “It is in the north somewhere.”

“Indeed? You must miss her, I feel sure.”

“Yes, certainly I do! No one ever had a better niece. Of course, you must not think that I approved of her putting you in the cellar, and I do hope she begged your pardon for it! But in the main she is a very good girl, I assure you!”

“I fear that the fault was mine. I had grievously offended Miss Grantham.”

Lady Bellingham regarded him with increasing favour. “I declare it is very handsome of you to say so, sir! To be sure, she was excessively put out by your wanting to give her twenty thousand pounds, not that I shall ever understand—however, that is neither here nor there!”

“I imagine,” he said, looking rather amused, “that the expenses of keeping up an establishment of this style must be heavy?”

“Crushing!” said her ladyship, not mincing matters. “You would find it hard to believe the shocking sum I spend on candles alone.”

“Is it worth it?” he asked curiously.

“That is just the tiresome part of it,” confided her ladyship. “I quite thought it would be when I moved from Green Street, but nothing has gone right with us since we came to this house.”

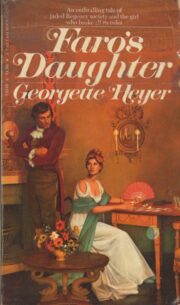

"Faro’s Daughter" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Faro’s Daughter". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Faro’s Daughter" друзьям в соцсетях.