“I know I shall. I shall enjoy that,” replied Miss Ravenscar. “Certainly. But take care you do not marry a man who wants to enjoy it too.”

Miss Ravenscar thought this over. “That’s horrid, Max.”

“It is unfortunately the way of a great part of the world.”

“Do you mean—do you mean that all the men who have wanted me to marry them only wanted my fortune?”

“I am afraid I do, Belle.”

Miss Ravenscar swallowed. “It is a very lowering thought,” she said, in a small voice.

“It would be if there were not plenty of men to whom your fortune will not matter a jot.”

“Rich men?”

“Not necessarily.”

“Oh!” Miss Ravenscar sounded more hopeful. “But how shall I know, Max?”

“Well, there might be several ways of knowing, but I can give you one certain way. If you should meet any man who would like to persuade you to elope with him, you may depend upon it that he is after your money, and nothing else. An honest man will rather ask permission to call in Grosvenor Square.”

“But, Max, they are all afraid of you!” objected Arabella.

“Depend upon it, you will one day meet a man who is not in the least afraid of me.”

“Yes, but—it is all so respectable, Max, and not exciting, or romantic! Besides, they have not all wanted to elope with me!”

“I should hope not indeed! Listen, Belle! I am asking no questions, and I don’t mean to spy on you, but I fancy you meet more men than your Mama or I know of. Before you decide to lose your absurd heart to one of them, consider whether you would care to present him to me, or to Adrian.”

“And if I would not, will he be the wrong sort of man?”

“Well, I’ll do that,” promised Miss Ravenscar, brightening. “It will be a very good kind of a game!”

Her brother drove her home, feeling that the morning had not been wasted.

He dined at Brooks’s that evening, and played faro afterwards, at the fifty-guinea table. When he rose from it, shortly after midnight, he saw that Ormskirk had walked into the cardroom, and was standing watching the fall of the dice at the hazard-table. Ormskirk looked up quickly as Ravenscar put back his chair, and moved across the room towards him.

“I thought you visited Brooks’s as seldom as I visit White’s,” remarked Ravenscar.

“Quite true,” Ormskirk drawled. “You, I fancy, came to White’s the other evening merely to find me.”

Ravenscar lifted an eyebrow.

“I,” said Ormskirk, flicking a speck of snuff from his sleeve, “came to Brooks’s in the hopes of finding you, my dear Ravenscar.”

“Ought I to be flattered?”

“Well, I must own that it is not my intention to flatter you,” replied his lordship, his thin lips curling into an unpleasant smile.

Ravenscar looked at him, slightly frowning. “How am I to take that, my lord?”

“I hope you may take it to heart. Let me tell you that I cannot congratulate you on the use you made of certain bills which I sold you. I must confess I am disappointed in you, my dear Ravenscar.”

“May I know how you are aware of what use I made of them?”

His lordship shrugged. “Inference, just inference!” he said sweetly.

“I suppose I must be extremely dull-witted, but I am still far from understanding what you mean. May I suggest that we step into the next room?”

“By all means,” bowed Ormskirk. “I can appreciate the delicacy of feeling which prompts you to shrink from discussing your cousin’s wife in such a public spot.”

Ravenscar strode over to the door that led into a small writing-room, and held it open. “I should certainly be loath to do so,” he replied. “My cousin, however, is not married nor is he likely to be.”

“You think not?” smiled Ormskirk.

Ravenscar shut the door. “I am quite sure of it.”

Ormskirk took out his snuff-box, and helped himself to a delicate pinch. “My dear Ravenscar, I am afraid you have been duped,” he said.

Ravenscar stood still by the door, stiffening a little. “In what way have I been duped?”

Ormskirk shut his snuff—box. “I must suppose that you have not encountered Stillingfleet, my dear sir.”

“I did not know that he was in town.”

“He arrived this morning. He has been staying at Hertford.”

“Well?”

“He drove to town by way of the Great North Road,” remarked Ormskirk pensively.

“So I should suppose. I do not yet perceive how his movements concern me.”

“But you will, my dear Ravenscar, you will! Stillingfleet, you must know, changed horses at the Green Man at Barnet. When he pulled out from the yard, he was in time to obtain art excellent view of a post-chaise-and-four, which was passing up the street at that moment. Ah, heading north, you understand!”

Mr Ravenscar was looking a little pale, and his mouth had hardened. “Go on!” he said harshly.

“He was much struck by the appearance of the lady in the chaise. He is not acquainted with Deb Grantham, but I could hardly mistake, from his admirable description of the lady’s charms! She had a young woman beside her—her maid, one supposes—and there was a quantity of baggage strapped on behind the chaise.”

Ravenscar smiled contemptuously. “Very possibly. Miss Grantham has gone into the country for a few days. I was aware that she had that intention.”

“And were you also aware that your cousin had the intention to accompany her?” inquired Ormskirk.

“I was not!”

“No, I thought not,” said Ormskirk gently.

“Are you serious?” Ravenscar demanded. “Do you tell me that Mablethorpe was with Miss Grantham?”

“That,” replied his lordship, “is what Stillingfleet told me. And he is, I fancy, fairly well acquainted with your cousin. He informed me that Mablethorpe was riding beside the chaise. Ah, I did mention that they were travelling in a northerly direction, did I not?”

“Oh, yes!” said Ravenscar. “You mentioned that at the outset, my lord. I may be dull-witted, but I collect that you wish me to infer that my cousin was eloping with Miss Grantham to Gretna Green.”

“It seems a fair inference,” murmured his lordship.

“It is a damned lie!” said Mr Ravenscar.

His lordship raised his brows in faint hauteur. “You should know better than I, my dear sir.”

“I think so indeed! I have known Mablethorpe since he was in short coats, and nothing would astonish me more than to learn that he had taken part in anything so vulgar as an elopement to Gretna. It is not in his character, my lord, believe me. Furthermore, I do not think that Miss Grantham has any more intention of marrying him than she has of becoming your mistress!”

“You would appear to be in the lady’s confidence,” said Ormskirk. “Or has she succeeded in deceiving you, I wonder?”

“She has certainly tried her best to do so, but I can assure you that she failed!” replied Ravenscar, with a short laugh. “I think I know Miss Grantham now, however mistaken I may have been in her at the outset! If Stillingfleet saw my cousin beside her chaise today, I imagine that he was escorting her to her friends in the country. That would certainly be in keeping with what I know of him.”

Lord Ormskirk made a graceful gesture of acceptance. “I that explanation satisfies you, my dear Ravenscar, who am I to cavil at it? I do hope that you will not suffer a rude awakening. You must not think that I do not find your faith in your cousin’s sense of propriety edifying: believe me, I do myself, I fear I am a cynic. No doubt we shall discover in time which of us was right.”

Chapter 16

Ravenscar strode home in a mood of some uneasiness. Lord Ormskirk’s story had alarmed him quite a much as it had angered him, and although he did indeed believe Mablethorpe to be incapable of so far forgetting what was due to his name as to elope with Miss Grantham to the Border he could not but recall his own faint surprise at hearing, that morning, that his cousin had suddenly taken it into his head to retire into the country for a few days’ shooting. Mr Ravenscar was well aware that his youthful relative, far from showing any sign of recovery from his passion for Miss Grantham, had been haunting St James’s Square for the past week. He bore all the marks of a man deeply in love, and nothing, Ravenscar was persuaded, had been farther from his intentions, when he had last seen his cousin, than a removal from town. Miss Grantham’s decision to visit friends in the country might, of course, have altered his lordship’s plans; and it certainly would have been very like him to have escorted her to her destination before himself travelling into Berkshire. Mr Ravenscar did his best to satisfy his own unquiet mind with this explanation, but could not quite succeed. He could not leave out of his calculations the inconvenient circumstance of his having relinquished the one sure hold he had over Miss Grantham. He thought he had gauged Miss Grantham’s character correctly, but the unwelcome suspicion that he might after all have been wrong would not be banished entirely from his brain. This possibility was so exceedingly unpalatable that it set him striding on at a greater rate than ever, his hand rather tightly clenched on his walking-cane, and his face set in more than ordinarily grim lines. At no time did Mr Ravenscar care to find himself mistaken; in this instance he had his own reasons for being doubly anxious that his judgement should not be found to have been at fault.

He reached his house soon after one in the morning, and was surprised, and not best pleased, to be met by his stepmother, swathed in a wrapper, and evidently labouring under a considerable degree of agitation. Long experience had made it unnecessary for him to inquire the cause of her being out of bed at such an hour, and he said, before she could speak: “Well, what has she been doing this time?”

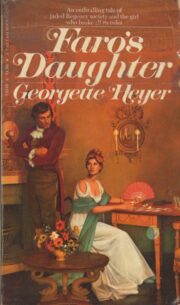

"Faro’s Daughter" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Faro’s Daughter". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Faro’s Daughter" друзьям в соцсетях.