“It serves you right!” she told him. “I dare say it may hurl you, and I am sure I don’t care!”

“Why should you indeed?” he agreed.

She began to wind her bandage round his right hand. “Is it any easier?”

“Much easier.”

“If I were a man you would not escape so lightly!”

“I dare say I should not. Or even if you had a man to protect you.”

“You need not sneer at Kit! To be sure, it is the height of folly for him to be falling in love with your sister, but he could not help that! Give me your other hand!”

He held it out. “You are a remarkable woman, Miss Grantham.”

“Thank you, I have heard enough about myself from you!” she retorted.

“Jade and Jezebel,” said Mr Ravenscar, grinning. “Harpy.”

“Also doxy!” said Miss Grantham, showing her teeth.

“I apologize for that one.”

“Pray do not trouble! It does not matter to me what you think me.” She pulled open one of the drawers in the dressing table, found a pair of lace ruffles in it, and began swiftly to tack these on to the sleeves of his shirt. “There! If you pull them down, the bandages will not be so very noticeable. I have left your fingers free.”

“Thank you,” he said, putting on his coat again.

“If you take my advice, you will go home now, and to bed!”

“I shall not take your advice. I am going to play faro.”

“I don’t want you in my house!” said Miss Grantham.

“It is not your house. I am very sure your aunt desires nothing more than to see me at her faro-table. She shall have her wish.”

“I cannot stop you behaving imprudently, even if I wished to, which I don’t,” said Miss Grantham. “If you are determined to remain here, you had better go in to supper, for I dare say you must be hungry.”

“Your solicitude overwhelms me,” returned Ravenscar. “I own I had expected at least a loaf of bread and a jug of water in my dungeon—until I learned, of course, that you had some idea of starving me to death.”

Miss Grantham bit her lip. “I would like very much to starve you to death,” she said defiantly. “And let me tell you, Mr Ravenscar, that Lucius Kennet is downstairs, and if you have any notion of starting—a vulgar brawl in my house, I will have you thrown out of it! There is Silas, and both the waiters, and my aunt’s butler, and my brother too, so do not think I cannot do it!”

“This is very flattering,” he said, “but I fear my fighting qualities have been exaggerated. It would not take all these people to throw me out of the house.”

“And in any event,” pursued Miss Grantham, ignoring this remark, “your quarrel is with me, and not with Lucius. He merely did what I asked!” She moved towards the door, and opened it. “Now, if you are ready, I will show you the way down the backstairs, so that no one shall know you have been up here.”

“You think of everything, Miss Grantham. I will go out back area-door, and come in again by the front-door, picking up my hat and cane on the way, which we were so thoughtless as to leave in my dungeon.”

She made no objection to this, but led the way down the back stairs again. As she was about to let him out of the house, an idea occurred to her, and she asked abruptly: “How came you to know that Ormskirk held the mortgage, and those bills?”

“He told me so,” replied Mr Ravenscar coolly.

She stared at him. “He told you so? Of all the infamous. Well! I have always disliked him excessively, but I did no dream he would behave as shabbily as that, I must say!”

“You have always disliked him?” he repeated, looking rather strangely at her.

She met his look with a kindling eye. “Yes!” she said. “But not, believe me, Mr Ravenscar, as much as I dislike you!”

Chapter 13

Five minutes later, Mr Ravenscar knocked on the front door. It was opened to him by Silas Wantage, and he walked into the house with his usual air of calm assurance.

Mr Wantage made a sound as of one choking, and stood stock-still, staring at him with bulging eyes. Mr Ravenscar me this bemused stare with a look of irony, but gave no sign of recognition. He merely held out his hat, and his cane, an waited for Silas to take them.

Mr Wantage found his voice. “Well, I’ll be damned!” he muttered.

“Probably,” said Mr Ravenscar. “Have the goodness to take my hat and cane!”

Mr Wantage relieved him of these, and said helplessly: “I dunno how you done it, but I won’t say as I’m sorry. It goes against the grain with me to tie up a cove as can plant me as wisty a facer as you did, sir!”

Mr Ravenscar paid no heed to this confession, but glanced at his reflection in the mirror, adjusted the pin in his cravat, smoothed the ruffles over his bandaged hands, and strolled across the hall to the supper-room.

His entrance created quite a stir. His hostess, who was sipping claret in the hope of steadying her nerves, choked, and turned purple in the face; Mr Lucius Kennet, standing by the buffet with a plate of salmon in his hand, said “Good God!” in a startled voice, and dropped his fork; the Honourable Berkeley Crewe exclaimed, and demanded to be told what had kept Mr Ravenscar from his dinner engagement; Sir James Filey was thought by those standing nearest to him to have sworn under his breath; and several persons called out to know what had befallen Ravenscar. Only Miss Grantham showed no sign of perturbation, but bade the late-comer a cool good evening.

He bowed over her hand, looked with a little amusement at Lady Bellingham, who was still choking, and said: “I’m sorry, Crewe. I was unavoidably detained.”

“But what in the world kept you?” asked Crewe. “I thought you had forgotten you were to dine with me, and sent round to your house to remind you. They said you had set out just after dusk!”

“The truth is, I met with a slight accident,” replied Ravenscar, taking a glass of Burgundy from the tray which a waiter was handing him. As he raised it to his lips, the ruffle fell back from his hand, and his bandages were seen.

“Good God, what have you done to your hand, Max?” asked Lord Mablethorpe, in swift alarm.

“Oh, nothing very much!” Ravenscar replied. “I told you I had met with a slight accident.”

“Have you been set upon?” demanded Crewe. “Is that it?”

“Yes, that is it,” said Ravenscar.

“I hope it may not impair your skill with the ribbons!” said Filey.

“I hope not, indeed,” answered Ravenscar, with one of his derisive looks.

“Gad, Ravenscar, do you suppose it was an attempt to stop you driving tomorrow?” exclaimed a gentleman in an old fashioned bag-wig.

“Something of that nature, I fancy,” said Ravenscar, unable to resist an impulse to glance at Miss Grantham.

“What the devil do you mean by that, Horley?” demanded Sir James belligerently.

The gentleman in the bag-wig looked surprised. “Why, only that there has been a great deal of money laid on the race, and such things do happen! What should I mean?”

Filey’s high colour faded; he muttered something about having misunderstood, and swung out of the room, saying that he would try his luck at the hazard-table.

“What’s the matter with Filey?” inquired Crewe. “He’s become devilish bad-tempered all at once!”

“Oh, haven’t you heard?” said a man in an orange-and-white striped waistcoat. “You know he was mad to marry one of the Laxton girls? Pretty child, only just out. Well, the Laxtons are trying to hush it up, but I had it from young Arnold himself that the filly’s bolted!”

“Bolted?” repeated Crewe.

“Vanished, my dear fellow. Can’t be found! No wonder our friend’s sore!”

“Well, I don’t blame her,” said Crewe. “Filey and a chit out of the schoolroom! Damme, it’s little better than a rape! But where did she bolt to?”

“No one knows. I told you she’d vanished. And the best of it is the Laxton’s daren’t set the Runners on to her track for fear of the story’s leaking out! Wouldn’t look well at all forcing a child of that age into marriage with a man of Filey’s reputation!”

“It wouldn’t come to that!” objected Mr Horley.

“Oh, wouldn’t it, by God? You don’t know Lady Laxton, when there’s a fortune at stake,” chuckled the man in the orange-striped waistcoat.

Lady Bellingham, feeling that her cup was now full to overflowing, cast a despairing look towards her niece, and wondered why a mouthful of cold partridge should taste of ashes.

“It is not to be supposed,” said Lord Mablethorpe carefully, “that Filey will wish to marry any female who shows herself so averse from his suit.”

“If you think that, you don’t know Filey!” said Crewe. “He would think it added a spice to matrimony.”

Under cover of this general conversation, Lucius Kennet had moved across the room to Miss Grantham’s side, and now said in her ear: “Do you tell me you persuaded him to give up the bills, me dear? Sure, you could have knocked me down with a feather when he walked in as cool as you please!”

“I have not got the bills,” she replied.

“You have not got them? Then what the devil ails you to be letting him go, Deb?”

“I didn’t. He escaped.”

He looked at her with suspicion. “He did not, then! I tied his hands meself. It’s lying you are, Deb: you set him free!”

“No, I did not. Only he asked me for a candle, and I let him have one, never dreaming what he meant to do! He burned the cord round his wrists, and when I went down to the cellar he was free: There was nothing I could do.”

He gave a low whistle. “It’s the broth of a boy he is, and no mistake! So that’s why his hands are bandaged! Will he be able to drive?”

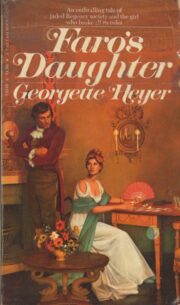

"Faro’s Daughter" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Faro’s Daughter". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Faro’s Daughter" друзьям в соцсетях.