“What I mean to do is no concern of yours! How did you come by that key?”

“I took it from Deb,” faltered Kit.

“Then take it back to her—with my compliments! And don’t forget to lock the door behind you!” said Mr Ravenscar.

Kit looked at him in a somewhat dazed fashion, but as Mr Ravenscar’s countenance wore a most forbidding expression, he picked up the lantern, and backed out of the cellar, obediently locking the door again, and removing the key. It seemed as though Ravenscar as well as Deborah was mad, and he was quite at a loss to know what to do. He went slowly upstairs again, and since there could be no object in retaining the key to a cell whose inmate refused to be set free, he made his way to Deborah’s side, and twitched her sleeve to attract her attention

She cast him a scorching glance, and turned away, but he followed her into the adjoining saloon, saying gruffly: “Here, you may take this!”

She looked in surprise at the key. “Why, what do you mean? Have you thought better of it? Is he still there?”

“I think he is mad!” said Kit, in an aggrieved tone. “I did try to set him free, but he would not let me! He told me to go to the devil, and said I was to give you back the key with his compliments. I do not know what is to be done. You have ruined everything.”

She took the key, almost as astonished as he was. “He told you to give it back to me?” she repeated. “He would not let you set him free-,”

“No, I tell you! I do not know what is the matter with him. One would say he must be in his cups, but he is not.”

“He means to fight it out with me,” she said, her eyes lighting up. “Well, and so he shall!”

She lost very little time in making her way down to the basement again, carrying this time one of the bedroom candles set out on a table at the foot of the backstairs, and guarding its frail flame from the draughts in the passage with her cupped hand.

Mr Ravenscar looked at her with a flickering smile as she entered his prison, and rose from his chair. “Well, Miss Grantham? What now?”

She shut the door, and stood with her back to it. “Why did you refuse to let my brother release you?”

“Because I would not be so beholden to him! He has not an ounce of spirit in him.”

She sighed, but shook her head. “I know, but the poor boy found himself in a sad quandary. He is a little spoilt.”

“He wants kicking,” said Mr Ravenscar, “and he will get it if he comes serenading my sister!”

“I don’t think she has the least idea of marrying him,” said Miss Grantham reflectively.

“What do you know of the matter?”

“Nothing!” she said hastily. “Adrian has told me a little about her, that is all. But I am not here to talk of your sister or of Kit either. Have you thought better of your rash words, sir?”

“If you mean, do I intend to give you back those bills, no!”

“You need not think I shall let you go, just because you would not permit Kit to set you free!” she said in a scolding voice.

“I thought you were not here to talk of your brother? You may forget that incident.”

She looked at him rather helplessly. “You were to have dined with Mr Crewe tonight. It will be all over town by tomorrow that you have disappeared. Already Sir James Filey is letting fall the most odious hints! He is upstairs now.”

“Let him hint!” said Ravenscar indifferently.

“If you do not race tomorrow, what excuse can you make that will not make you appear ridiculous?”

“I have no idea. Have you any suggestion to offer me?”

“No, I have not,” she said crossly. “You think I do not me to keep my word, but I do!”

“I hope you mean to bring me a pillow for the night.”

“I don’t. I hope you will be excessively uncomfortable,” snapped Miss Grantham. “If I dared, I would let you starve death here!”

“Oh, don’t you dare?” he asked. “I had thought there was limit to your daring—or your effrontery!”

“I have a very good mind to let Silas come down and bring you to reason!” she threatened.

“By all means, if you imagine it would answer.”

“I will allow you half an hour to make up your mind or and for all,” she said, steeling herself. “If you are still obstinate you will be sorry!”

“That remains to be seen. I may be sorry, but you will get your bills, my girl, I promise you.”

“It will be quite your own fault if you catch a cold do, here,” she said. “And I dare say you will, for it may be damp!”

“I have an excellent constitution. If you mean to leave me now, do me the favour of allowing me to keep the candle!”

“Why should you want a candle?” she asked suspiciously,

“To frighten away the rats,” he replied.

She cast an involuntary glance around the cellar. “Good God are there rats here?” she said nervously.

“Of course there are—dozens of ’em!”

“How horrible!” she shuddered. “I will leave you the candle but do not think by that I shall relent!”

“I won’t,” he promised.

Miss Grantham withdrew, feeling baffled.

Upstairs, she found that Lord Mablethorpe had vanished and guessed that he had slipped away to talk to Phoebe in the back-parlour. Lucius Kennet came strolling up to her, and asked her under his breath how the prisoner was faring. She whispered that he was determined not to surrender. Mr Kennet grimaced. “You’d best let me reason with him, me darlin’”

“I will not. You have done enough mischief!” she said, remembering his perfidy. “How dared you trick him in my name. I told you I would not have it!”

“Ah, now, Deb, don’t be squeamish! How was I to kidnap him at all, without he walked into a trap?”

She turned her shoulder, and went away to watch faro-players, resolutely frustrating an attempt upon her aunt’s part to catch her eye.

The half-hour she had promised to allow Mr Ravenscar for final reflection lagged past, and she found herself at the end of it without any very definite idea of how she was to persuade him to submit if he should still prove obstinate. Her aunt was leading the way downstairs to the first supper when she paid her third visit to the cellar, and she could not help thinking that her prisoner must, by this time, be feeling both cold and hungry.

She unlocked the cellar door, and went in, closing it behind her. Mr Ravenscar was standing beside his chair, leaning his shoulders against the wall. “Well?” she said, in as implacable a tone as she could.

“I am sorry you did not send your henchman down to me,” said Ravenscar. “Or your ingenious friend, Mr Kennet. I was rather hoping to see one, or both, of these gentlemen. I meant to shut them up here for the night, but I suppose I can hardly serve you in the same way, richly though you deserve it!”

He had straightened himself as he spoke, and moved away from the wall. Before Miss Grantham could do more than utter a startled cry, his hands had come from behind his back, and he had grasped her right arm, and calmly wrested the key from her clutch.

“Who let you go?” she demanded, quivering with temper. Who contrived to enter this place? How did you get your hands free?”

“No one let me go. Or, rather, you did, my girl, when you left me a candle.”

Her eyes flew to his wrist, and a horrified exclamation broke from her. “Oh, how could you do that? You have burnt yourself dreadfully!”

“Very true, but I shall keep my appointment tomorrow, and you will not get your bills,” he returned.

She paid very little heed to this, being quite taken up by his hurts. “You must be suffering agonies!” she said remorsefully. “I would never have left the candle if I had guessed what you meant to do!”

“I do not suppose that you would. Don’t waste your sympathy on me! I shall do very well. We will now go upstairs, Miss Grantham, and set Sir James Filey’s mind at rest. Unless, of course, you prefer to remain here?”

“For heaven’s sake, don’t lock me in here with rats!” begged Miss Grantham, for the first time showing alarm. “Besides, you cannot go into the saloons like that! You will very likely die if nothing is done to your hands! Come up with me immediately! I will put some very good ointment on them, and bind up your wrists, and find you a pair of Kit’s ruffles in place of these! Oh dear, what a fool you are to do such a thing! You will never be able to drive tomorrow!”

“I don’t advise you to bet against me,” he said, looking down at her with a good deal of amusement. “Do you really mean to anoint my hurts?”

“Of course I do! You do not suppose that I am going to have it said that you lost your race through my fault, do you?” she said indignantly.

“I was under the impression that that was precisely what you meant me to do.”

“Well, you are wrong. I never thought you would be so stupidly obstinate!”

“Were you going to release me, then?”

“Yes—no! I don’t know! You had better come up the backstairs. You may tidy yourself in my brother’s room while I fetch the ointment, and some linen. I wish I had never laid eyes on you! You are rude, and stupid, and I was never so plagued by anyone in my life!”

“Permit me to return the compliment!” he said, following her along the passage.

“I will make you sorry you ever dared to cross swords with me!” she flung over her shoulder. “I’ll marry your cousin, and I’ll ruin him.”

“To spite me, I suppose,” he said satirically.

“Be quiet! Do you want to bring the servants out upon us?”

“It is a matter of indifference to me.”

“Well, it is not a matter of indifference to me!” she said.

He laughed, but said no more until they had reached Kit’s room upon the third floor. Miss Grantham left him there with the candle, while she went off to hunt for salves and linen bandages. When she returned, he had pulled off his coat, and discarded the fragments of his charred ruffles, besides straightening his tumbled cravat, and brushing his short black locks. The backs of his hands were badly scorched, and he winced a little when Miss Grantham smeared her ointment over them,

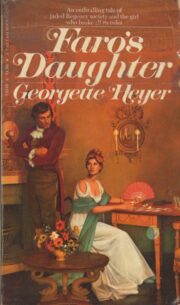

"Faro’s Daughter" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Faro’s Daughter". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Faro’s Daughter" друзьям в соцсетях.